Exclusive

Exclusive  Exclusive

Exclusive After more than one year after the Veterans Affairs Department stood up its new Office of Accountability and Whistleblower Protection. senior executives still make...

After more than a year since the president signed the Veterans Affairs Accountability and Whistleblower Protection Act into law, the office that handles whistleblower disclosures and disciplinary actions for the agency’s employees is still establishing itself as one that can quickly and accurately address poor performance and misconduct — and as an organization that employees can trust.

After more than a year since the president signed the Veterans Affairs Accountability and Whistleblower Protection Act into law, the office that handles whistleblower disclosures and disciplinary actions for the agency’s employees is still establishing itself as one that can quickly and accurately address poor performance and misconduct — and as an organization that employees can trust.

According to a new report from the Veterans Affairs Department, the Office of Accountability and Whistleblower Protection (OAWP) still needs more staff, dedicated resources and more specific authority to fully manage disciplinary actions and whistleblower complaints for all of the department’s employees — from the bottom ranks of the General Schedule to the Senior Executive Service.

The report, which VA submitted to lawmakers at the end of June, was congressionally mandated under the accountability act.

But for good government groups and federal employment attorneys, VA’s culture and history of whistleblower retaliation is stymieing the department’s employees from fully embracing OAWP as a resource.

“We recommend that our clients go to the Office of Special Counsel, because our clients don’t trust [OAWP,]” said Cheri Cannon, managing partner and federal employment attorney at the Tully Rinckey law firm. “It’s going to take awhile to establish themselves as an office … that can be trusted.”

“It’s a hard sell for people who have lived in this system for a long time,” she added.

The House Veterans Affairs Committee, which regularly sends staffers out to visit VA facilities, said the overall perception of the new accountability office and the law itself seems relatively positive. Managers understand what the law does, a committee aide told Federal News Radio.

The House VA Committee is scheduled to review VA’s implementation of the accountability act at a hearing next week. The goal, the committee aide said, is to start a conversation and begin the long process of evaluating whether the law is meeting VA’s needs and “creating a culture of sustained accountability.”

Both VA and the American Federation of Government Employees are expected to testify at next week’s hearing.

The accountability act, which the president signed on June 23, 2017, codified VA’s new Office of Accountability and Whistleblower Protection (OAWP) into law. The president signed an executive order earlier in 2017 that established OAWP as a new entity, that would “elevate accountability to the highest level.”

But for OAWP, the first year has been characterized by staffing shortages, the department said. The office is authorized for 102 full-time employees but had 73 on board as of June 1. Several new hires were pending, VA said in its report.

Human resources specialists and management analysts have filled out the OAWP, but the office is seeking authority to hire attorneys to work specifically within the accountability office.

“This change is to ensure OAWP access to agency information in a manner and scope similar to the Office of Special Counsel, while providing a similar degree of protection to any information gathered under these auspices,” VA wrote in its report. “The addition of lawyers to the staffing resources of OAWP is necessary to ensure the quasi-independent nature of OAWP.”

On the other hand, it may not be such a huge lift for VA’s accountability office to handle its current workload with a staff of 73-to-102 employees, said Elizabeth Hempowicz, director of public policy for the Project on Government Oversight.

OSC, which investigates prohibited personnel practices and cases of whistleblower retaliation for the entire government, has about 150 full time employees, according to the agency’s principal deputy special counsel.

OSC has a comparable mission to the VA’s OAWP — but with broader responsibilities across all of government, Hempowicz said.

OAWP is also requesting a designed, line-item budget, which the department argued is “essential” to maintain quasi-independence.

Currently, “the office receives its funding through reimbursement from the very entities it investigates,” VA wrote in the report. “This arrangement also leaves the office’s future operations vulnerable to zeroing out through administrative action within the department.”

Questions about the OAWP’s staffing and resources are a likely topic of conversation at an upcoming hearing before the House Veterans Affairs Committee, which is scheduled for July 17.

In advocating for the accountability act, former VA Secretary David Shulkin and other agency leaders said time and again that they needed congressional authority to more quickly discipline and fire employees for poor performance and misconduct.

OAWP said it needs more authority to investigate and propose disciplinary actions for a broader range of senior leaders. Under the current accountability act, OAWP can statutorily investigate and discipline medical center directors, chiefs of staff and nurse executives.

The office doesn’t authority to discipline medical center assistant and associate directors, OAWP’s report said.

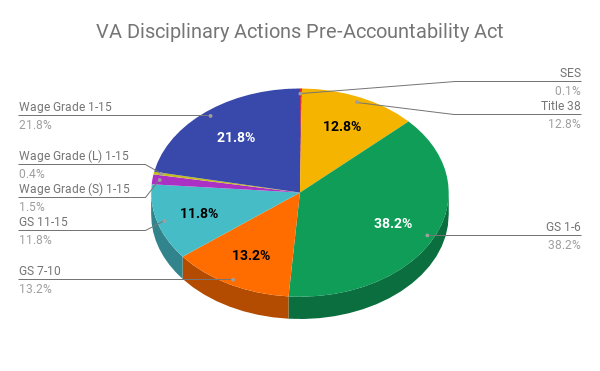

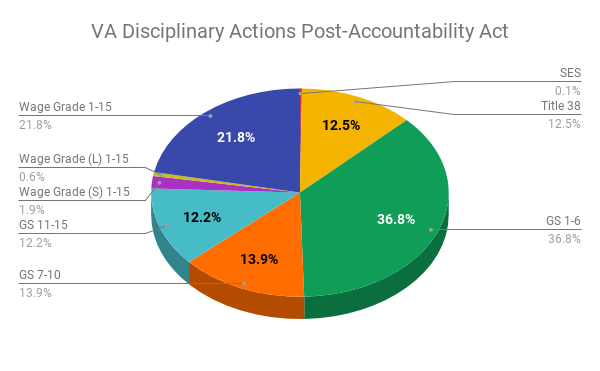

VA’s report also compares employee disciplinary actions for the three years prior to signing of the accountability act with actions taken during the first year of the new law.

The department’s disciplinary action data confirms what biweekly reports published on VA’s website have shown for much of the past year: The agency proposed more disciplinary actions and attempted to fire more people during the first year of the accountability act than it had during the previous year. VA is also settling those disciplinary cases far less now than it had in prior years. Disciplinary actions against senior executives continue to make up a small fraction of total actions at the department.

“A year-and-a-half after this office was created and they got new authorities, you’d expect the numbers at least to show a different picture,” Hempowicz said of the disciplinary actions described in the report. “They had the opportunity in this report to explain why they didn’t, and I don’t see that in the text of the report.”

The majority of disciplinary actions still occur within the lower ranks of the VA workforce, among GS-1-6 and wage grade employees. VA took slightly more disciplinary actions against GS-7-10s and GS-11-15s within the past year compared to the previous three years before the passage of the accountability act.

Additional authority may help VA propose and resolve more disciplinary actions against senior executives, which continue to make up a slim margin of VA’s total disciplinary moves. In the three years before the signing of the accountability act, members of the Senior Executive Service made 0.1 percent of total disciplinary actions at the department.

After the accountability act’s signing, SES again made up 0.1 percent of total disciplinary actions.

To be clear, VA has significantly more employees at the GS-1-6 level than senior executives. Office of Personnel Management data from December 2017 show 364 career SES and more than 88,000 employees at GS-1-6, meaning there are certainly more opportunities to take disciplinary action against a larger body of low-ranking employees.

For the House VA committee, the numbers are important, but members are more interested in whether the department is doing the right thing when the situation arises, the aide said.

The committee was pleased to see the number of removals for low-ranking employees dropped slightly and remained relatively steady compared to previous years, the aide said.

OAWP recommended 23 total disciplinary actions for senior executives over the past year. In more than half of the cases, the department reached a decision or outcome of lesser punishment than what the OAWP originally recommended. In six cases, the executives retired or resigned somewhere during the disciplinary and appeal process.

Details of the 23 disciplinary actions, listed by VA administration, are below.

What is perhaps more noticeable, however, is the department’s stark drop in employee settlements.

Former Secretary Shulkin last July announced his decision to require senior level approval for employee settlements of $5,000 and above.

Since then, “it’s been virtually impossible to settle anything,” Cannon said.

The graph below shows settlement data from just one year before the Accountability Act (2015-2016) compared to the first year after the new law. VA settled far less with employees of nearly every personnel in 2017-2018, compared to 2015-2016 and every other year for which the department provided data in its most recent report.

The graph below compares one year of data from the years prior to the accountability act signing (2015-2016) to one year (2017-2018) under the new law. Last year, the department settled at rate a that’s anywhere from six-to-10 times lower than the rate they settled employee disciplinary cases in 2015-2016.

Scroll over the graph for more detailed data.

Cannon and other federal employment attorneys have lamented the decision to require top-level approval for employee settlements over $5,000. Settlements typically save both the agency and the employees time and litigation costs.

VA’s report comes as the agency’s inspector general has agreed to review implementation of the accountability, at the request of several members of the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee.

VA employees have told Federal News Radio they’ve felt demoralized and undervalued in the wake of the new accountability law. The senators, having heard similar stories, are concerned the agency is using new authority to shorten the time employees typically had to improve their performance, particularly after one or two offenses.

Questions about employee morale will likely surface at the House committee hearing next week. Peter Shelby, VA’s assistant secretary for human resources, told House lawmakers that morale was high during a hearing on VA hiring challenges last month.

Lawmakers will also likely question what IT systems VA will need to provide a clearer picture of disciplinary actions at the department. The House committee aide said it was disappointed VA’s report lacked more details on how long the department is taking to resolve issues of poor performance or misconduct.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED

Exclusive

Exclusive

Exclusive

Exclusive