Dept. of Ed.’s decision to shrink telework options leaves employees questioning motives

After spending years building its telework policy into one of the most popular programs of its kind, the Education Department will significantly reduce the ability...

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

After spending years building its telework policy into one of the most popular programs of its kind, the Department of Education will significantly reduce the ability of its employees to work from home or from an alternative workplace.

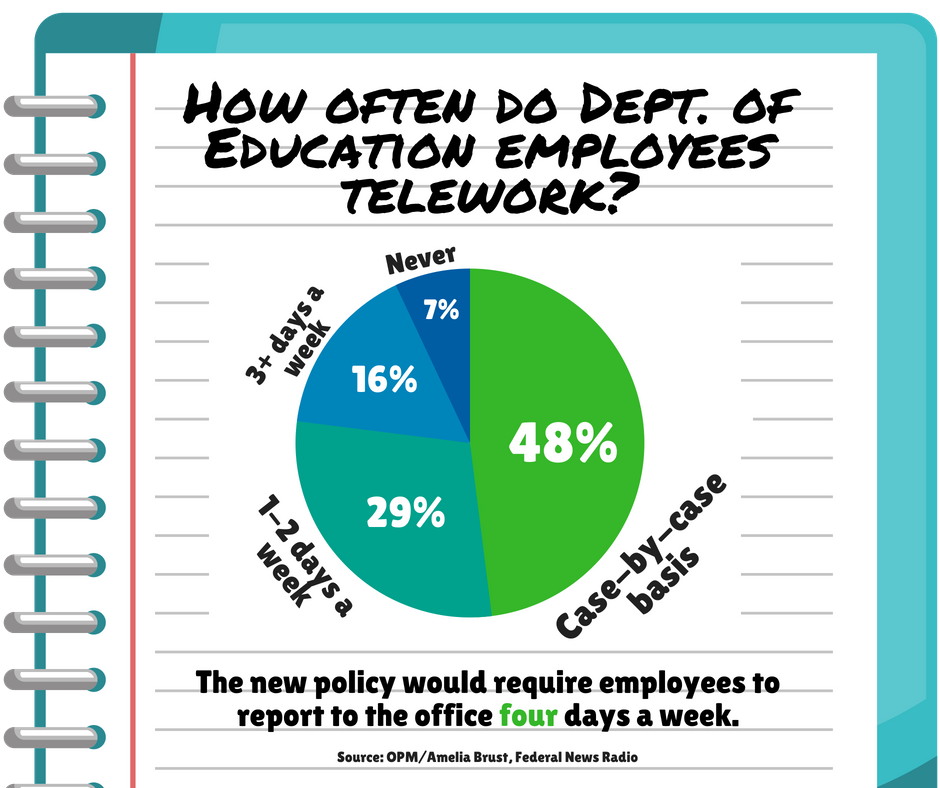

The policy change, announced May 31 through an internal memo obtained by Federal News Radio, will require most employees to work in the office at least four days a week, a significant turnaround for an agency that until recently had encouraged greater adoption of telework.

The sudden change has many workers questioning how the agency’s headquarters facilities will accommodate an influx of workers who, under the previous policy, would have been working remotely.

Education’s Office of Management released its new telework policy just two months after it broke off negotiations with the American Federation of Government Employees and unilaterally implemented its own terms on the agency’s workforce.

Prior to the all-staff email announcing the changes to telework, the agency’s new labor terms excluded any language about the popular agency program.

“[The Education Department] has a greater need for physical presence in our office. Employee presence will enhance collaboration between program office components and strengthen our delivery service internally and externally,” the Office of Management wrote in a “frequently asked questions” guide sent to agency employees along with the telework memo.

According to one Education employee, who requested anonymity because they did not have permission to talk to the press, agency management had talked behind closed doors about revamping the telework policy, but rank-and-file workers were left in the dark about those conversations until they received the email announcing the change.

“There had been chattering that the telework policy was being evaluated,” the employee said in an interview. “Everybody kind of knew that, but there was no formal announcement of the change. That’s just it, everybody knew what was being discussed, and then here it comes.”

The agency’s new policy comes after the Agriculture Department made major cutbacks to its own telework agreement in January, allowing employees to take only two teleworking days per pay period, or about four days per month. Under its previous policy from 2014, USDA employees could telework full-time.

Compared to USDA, the Education Department has allowed more time for its employees to adjust to the new policy. The changes will take effect Oct. 1, the first day of fiscal 2019, and employees must sign new flexible work agreements by Aug. 15.

USDA, on the other hand, only gave its workforce about a month to adjust to the changes but gave some of its employees an extra 30 days to prepare for the new telework policy.

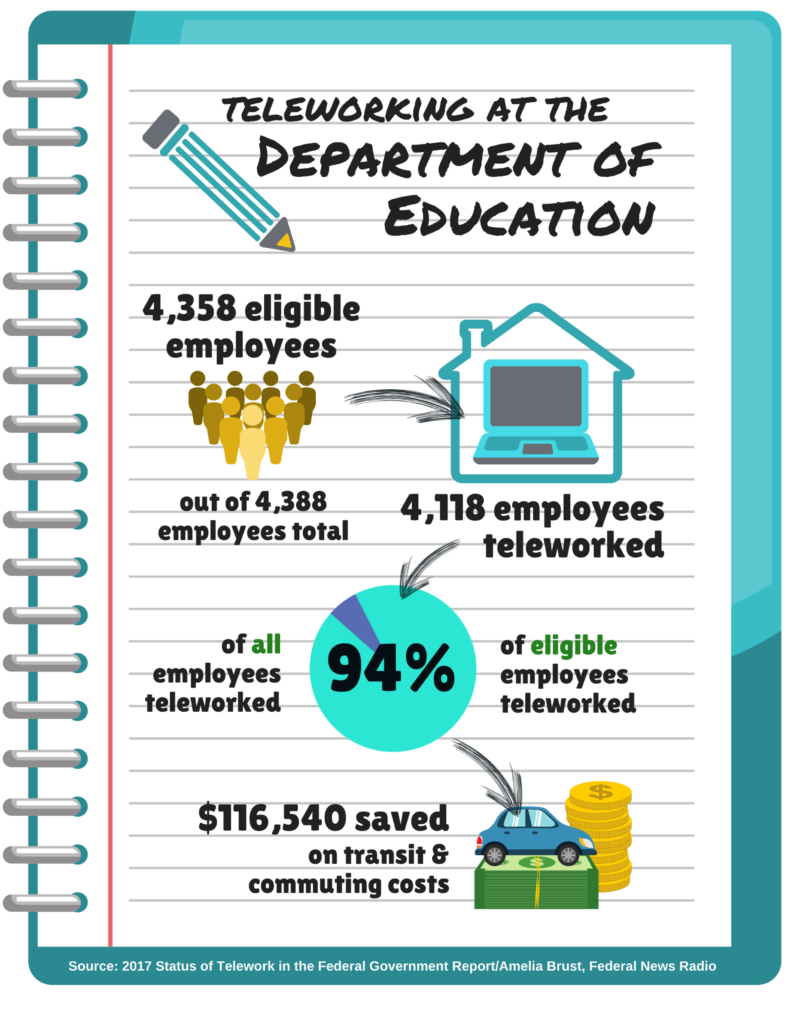

According to the Office of Personnel Management’s most recent report to Congress, 94 percent of Education employees were eligible for telework in 2016, and the same percentage made use of the policy that year.

OPM found 16 percent of Education’s workforce of 4,388 employees teleworked three or more days a week — a work schedule not permitted under the new policy.

Another 29 percent of Education employees reported teleworking one or two days a week, while nearly half of its workforce opted to telework on a case-by-case basis in 2016.

“If the question is what percentage of employees will lose telework in some fashion as a result of this, at a minimum, 75 percent, I would say,” one Education Department employee said.

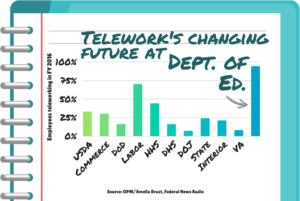

The Obama administration encouraged agencies to offer telework to its employees. OPM data shows a more than 10 percent increase in telework use at Education between 2015 and 2016 alone.

Workplace logistics: ‘Where do we put people?’

Over the past few months, the department has conducted an impact study across all offices looking at the implications the new policy will have on office space, IT infrastructure and physical security.

Elizabeth Hill, an agency spokeswoman, told Federal News Radio there is “plenty of office space” in the agency’s buildings to accommodate all employees ahead of the new telework policy.

Education employees, however, say they still have concerns over how the agency’s headquarters buildings and field offices will make room for workers who previously didn’t have a defined workspace, but will need one in the coming months.

An agency employee said “a few floors” of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Building in Washington, D.C., have already undergone renovations. Those floors, he added, have very few permanent offices, and mostly consist of small cubicles and “hoteling spaces,” or unassigned desks telework employees can reserve for upcoming office days.

“We have downsized our space in several federal buildings triggering more employees to take advantage of the opportunity to telework,” the agency wrote in OPM’s telework report. “Employees that telework three or more days a week no longer have designated spaces. They are able to reserve a hoteling space when they are in the office.”

Hill said Education has sought to consolidate the agency’s office space under an Obama-era memo.

“The agency’s space modernization initiative is one part of the federal government’s plan to reduce its overall real property footprint nationwide,” she said. “[Education Department] construction projects associated with the project kicked off in 2014 will continue, if funding is available, over the next several years. The agency will keep the pending telework changes in mind as new space designs are developed in the out years.”

Another employee said under the previous telework agreement, entire agency program offices had agreed to work remotely.

“A decision was made, ‘This entire office will telework in order to save on space and get them out,'” the employee said. “Those offices now, unless they’re outside the commuting area, they’re coming back in.”

AFGE Local 2607 President Sharon Harris, a former agency employee who left in December 2017, said Union Center Plaza (UCP), one of three headquarters facilities located in D.C., has reached capacity.

“They have a large population teleworking, and it was allowable because it was a remedy to where do we put people,” Harris said. “They got rid of the [agency’s] K Street location and the Capitol Place location. And then we had to merge employees in both those locations in the three remaining [buildings].”

Some Education employees also question how an existing program allowing employees to share parking spaces would continue under the new telework policy.

“The transportation team will evaluate all current and new requests in light of this new development and provide impacted employees with additional information,” the Office of Management wrote in its FAQ to employees.

Education’s previous telework policy not only reduced the need for office space, but also cut the time and money its employees spent commuting to the office.

According to the OPM telework report to Congress, Education employees saved more than $100,000 annually on transportation costs as a result of its broad adoption of telework.

Shrinking Education’s workforce

For all the changes this new telework policy will bring, Education employees say they’re unsure why the agency would curtail the popular program.

“As the department continues to assess its staffing needs, determine how best to utilize the talents of [Education Department] employees, and ensure we are being good stewards of taxpayer dollars, the telework policy has been updated to enhance collaboration between program offices and improve customer service to our internal and external stakeholders,” Hill said.

And yet, having heard no complaints about telework in their program offices, some employees see the scaled-back policy as part of a larger effort to reduce the size of the agency’s workforce.

Under the Trump administration, Education’s workforce has decreased by nearly 400 positions.

The agency continues to keep a hiring freeze in place, more than a year after the Office of Management and Budget ended a governmentwide hiring freeze at the beginning of the Trump administration.

Within the last year, the agency has also offered buyouts and early retirements to its workforce.

Hill said 69 Education employees separated from the agency in January 2018 under its Voluntary Early Retirement Authority (VERA) and Voluntary Separation Incentive Payments (VSIP) programs.

And in some cases, the new telework agreement has encouraged employees to look for other jobs.

“Within Education, morale is extremely low already and there is, at least in my immediate vicinity, almost everyone is actively and not really hiding it, looking for other work outside the agency,” an Education employee said, who confirmed he was leaving the agency.

Hill said the Education Department had 4,018 employees in February 2017. As of May 2018, the agency had 3,742 employees on its payroll.

The future of government telework?

Rep. Gerry Connolly (D-Va.), who co-sponsored the 2010 Telework Enhancement Act along with Rep. John Sarbanes (D-Md.), told Federal News Radio that Education’s policy change unfairly looks down on the importance of telework.

“There has to be some data to justify it and there isn’t. And so it just becomes a cultural bias — if I can’t see you, you clearly aren’t working. If I don’t see you in your office or your cubicle, you’re clearly goofing off,” Connolly said in an interview. “Telework isn’t just something where somebody says, ‘Yeah, if you want to take the day off of work, go ahead and we’ll call that telework.’ That’s not what telework is. This structured program has serious, positive benefits across the board.”

Connolly added that the reduction of telework at Education will hurt its ability to recruit the next generation of agency workers.

“If you don’t offer it in a serious, substantial way, you’re not going to get future employees,” he said.

AFGE’s Harris said the union has expressed similar concerns about recruiting new employees, or retaining younger employees who expect a more accommodating work schedule.

“They have a lot of employees who recently came on board because they were told that telework was part of the benefits package. Millennials now, I think, lean toward work environments that have a lot of flexibility,” Harris said. “So now you’re talking about taking them away. How much of that population of employees does the department expect to stick around?”

In light of telework changes at USDA and Education, Connolly said he’s working on new legislation that would protect existing telework agreements.

“If nobody can telework more than one day a week, well, that really does fly in the face of the whole purpose of telework, which is to stay flexible,” Connolly said, adding that the bill would define telework as allowing agency employees to work remotely at least two days a week.

In a statement, Sarbanes said Education’s plan to reduce telework would serve as a step backward for the agency.

“The Department of Education’s plan to drastically scale back its employee telework program is just the latest barrage — in a string of mean-spirited attacks — by the Trump administration on our nation’s hardworking civil servants,” Sarbanes said. “Numerous reports and studies demonstrate that telework programs not only improve productivity, but also save taxpayer money by increasing efficiency, strengthening employee retention and reducing costs for federal office space. Simply put, telework programs make our government work better for the American people.”

Hiring and retention could get harder

The President’s Management Agenda lists building a 21st-century federal workforce as one of its 14 cross-agency priority goals, and as one of three “drivers of transformation.”

But in order to get that agenda off the ground, Connolly said agencies need to offer a competitive benefits package to new hires.

“If we’re going to compete with the private sector, we’ve got to make sure that there are attributes to the federal workplace that can match those of the private sector, that make it a more desirable place in which to work,” Connolly said.

Cathie McQuiston, the deputy general counsel at AFGE, said Education’s new telework policy will make it harder for the agency to recruit or retain top talent.

The Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights, for example, counts many attorneys among its workforce of 600 employees.

“There’s a lot of attorneys that work in that office doing civil rights enforcement work, and a lot of them have come from other, more high-paying jobs at law firms,” McQuiston said, adding that the federal government, thus far, has offered a more favorable work-life balance than the private sector. “People have left those jobs to come and do work at Education, while taking a significant pay cut. One of the appealing things is the ability to not have to commute to [agency] offices.”

The Office of Civil Rights has 12 enforcement offices throughout the country, with each office covering four-to-five states.

Prior to the change in telework policy, OCR employees could live several hours away from the office they reported to, provided they were willing to travel to the office about once per pay period. But traveling that distance four times a week, however, may prove too strenuous for some.

“Someone may live in Los Angeles, even though they’re assigned to the San Francisco office because they haven’t had to report,” McQuiston said. “Now they’ve got to either find a new job or several days a week fly to San Francisco to comply with that new policy.”

The new telework policy raises a number of new work-life challenges for Education employees, who say they’ve considered moving or finding a new job. One agency employee just had a baby, while another is pregnant. Both cited increased child-care costs and less time spent with their children as concerns they have with the new telework policy.

Latest Workforce News

“You have a large population of employees that were allowed to work out-of-state, but are on record as having a duty station in the headquarters area. So those people now will have to incur, I would say, the great expense of having to be in an office at least four days a week,” Harris said.

The Office of Management’s memo to employees says remote workers outside the “local commuting area” of an agency facility will be allowed to continue to work remotely.

The agency said it would make reasonable accommodations for employees with disabilities.

Several Education employees told Federal News Radio they were unsure who would make the final determination of whether they were in the local commuting area of their nearest agency facility.

Hill said the agency would soon provide guidance to employees that would better define local commuting areas.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jory Heckman is a reporter at Federal News Network covering U.S. Postal Service, IRS, big data and technology issues.

Follow @jheckmanWFED