Agencies drag employees toward open-office designs

An exclusive Federal News Radio online survey shows feds are happiest when they work in offices where they can close their doors. Cubicles and open spaces with ...

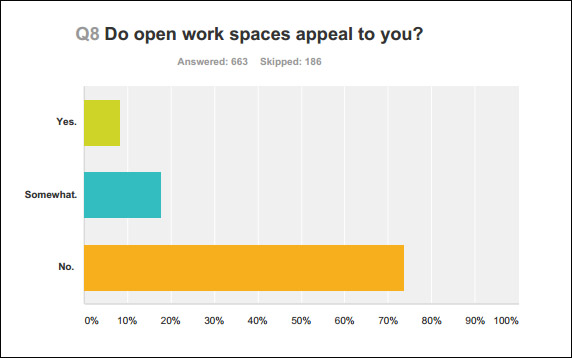

When asked whether open work spaces appeal to federal employees, 74 percent of feds said no in an exclusive Federal News Radio survey.

Agencies are dragging their employees kicking and screaming into the supposedly collaborative era of open-office design.

The results of an exclusive Federal News Radio online survey showed feds are happiest at work when they can close their doors. They are least likely to enjoy their offices when they work in cubicles or open spaces with low or no partitions separating them from colleagues. That is a recipe for distraction and lower productivity, they said repeatedly in comments throughout the survey.

When asked whether open work spaces appeal to them, nearly three-quarters of the federal employees who answered the question said “no.” Pick your metaphor: they compared it to working in a bathroom stall with no door or a fishbowl. Their chief complaints centered around noise, with some saying they resorted to wearing earphones to drown out others’ conversations.

“The low/no partitions between work spaces make it extremely difficult to concentrate when coworkers are having conversations,” wrote an intelligence analyst who said they worked in a cubicle at their agency in Virginia. “Not to mention, you end up hearing personal details about coworkers’ lives (arguments with spouses, medical information, etc.) that you just don’t want to know.”

“It is utterly exhausting to be without privacy or the ability to have personal time for 9+ hours straight. What I wouldn’t give for the ability to hear myself think some days,” they continued, echoing sentiments shared widely by other survey respondents.

The survey is part of Federal News Radio’s three-day special report, The Federal Office of the Future, where we’ll explore how federal office space is changing, how that affects employees and what agency managers need to be aware of. The unscientific online survey was conducted June 21-28, 2015. The vast majority of respondents—849 out of 907—identified as federal employees.

Federal employees also complained about tight quarters, with some saying the handicapped bathroom stalls in their offices dwarfed their personal work spaces. (They knew because they had measured the two.)

But the loudest groans came from federal employees who do not have assigned desk space. Instead, they sit at whichever work station is available. They store their belongings in secure spaces that may be across the room or in another room altogether.

“Whoever gets in the office first takes the ‘prime’ spots. I get more work done now when I am teleworking from home,” said a Washington-based Homeland Security Department employee who works in program management. “Also, no longer having a desk presents a challenge—we have small, rolling cubbies that we are supposed to keep our files, supplies, etc. in—they are not big enough. I had to bring most of my work files home.”

The concept of an open-office plan confounded those who said they worked with sensitive data that must be kept under lock and key, or supervisors who said they had to leave their desks in order to have conversations with employees.

In contrast, less than a quarter of survey respondents said they liked their current office space better than previous ones. Most of the respondents who like their work space, not surprisingly, said they work in enclosed offices.

“I need a quiet and private space to keep my mind focused on very detailed work in order to present very accurate financial reports for [the Office of Management and Budget] and Treasury,” said a Justice Department employee who works in financial management.

“I have wall space that I can decorate with personally-owned artwork; I can host a private meeting; I have sufficient desk space to spread out my work and leave it out for the next day (because I have a locking door),” wrote another respondent, who works in program management at the Government Printing Office.

Yet more federal agencies are taking their employees out of private offices and moving them to cube farms or shared-desk environments. Proponents acknowledge that money is a big driver. The White House’s “Freeze the Footprint” initiative in 2013 directed agencies to halt office sprawl. That spawned a more aggressive “Reduce the Footprint” initiative, which launched earlier this year.

“We now are asking [agencies] to take a strategic five-year view and our expectation is for them to be able to accomplish more significant reductions,” OMB Controller David Mader told Federal News Radio in March. “We are going from freeze it to being more proactive, establishing standards and working with the General Services Administration to consolidate offices and look for innovative ways to shrink [the] overall footprint.”

GSA, as the government’s landlord, has led by example. It transformed its headquarters in 2013 into a giant open space in which employees of all ranks work. That move saved $24.4 million because it let the agency consolidate leases, according to then-Administrator Dan Tangherlini. By encouraging employees to work regularly from home, the agency was able to squeeze 4,000 workers into a space originally fit for 2,500.

The agency’s leading researchers on the subject said the move toward open-office design benefits employees as well. The idea that both managers and rank-and-file employees would work in the same space is a “democratization of the workplace,” said Judy Heerwagen, a program expert in GSA’s Office of Federal High Performance Green Buildings, in an interview with Federal News Radio’s Federal Drive.

“There are organizations where the managers want to see everybody. They want big open spaces so they can see people at work and feel a sense of importance that everyone is working,” she said. “And workers themselves like to see other people at work. It’s stimulating to see others.”

But what about the noise?

“People also say that they learn things from accidental conversations in open space, by happening upon someone or overhearing something,” said GSA’s Chief Sustainability Officer, Kevin Kampschroer, who runs the Office of High Performance Green Buildings. “It’s kind of like, yes, it’s bothersome, but on the other hand, it’s useful.”

Yet, so is medicine, and few people would choose to take it voluntarily.

What is the best office design? Ask the employees.

Cubicle workers who once had enclosed offices bemoan the loss of control over their environments, the survey revealed.

“I could regulate the sound and lighting of my environment,” said a program manager at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases’s Rockville, Maryland, offices.

“I had a private office previously that allowed me to work in quiet. Now my colleagues just pop up like prairie dogs and ask me questions all day,” said a Virginia-based law enforcement professional at the Interior Department.

Giving employees control over—or at least a say in—an office’s new design is the best way of ensuring they support the change, said Cary Cooper, a professor at Manchester Business School in England who is considered an authority on health and well-being in the workplace.

“Every group of employees’ needs are different. You need to engage them,” he told Federal Drive host Tom Temin. “If I were [a manager], I’d sit with staff and ask what we should do about it. You can come up with weird and wonderful ideas.”

Some professionals, such as day traders, thrive on the activity of an open-plan office, he said. But for others, such as accountants handling tax returns, that scenario is a nightmare.

He once advised an advertising agency on redesigning its office space. The company’s employees suggested a “chill room” where they could relax in dim light and listen to the bubbling of an aquarium, he said. They designated another room for brainstorming ad campaign ideas. That room had an open plan to stimulate ideas and conversation.

Federal employees who answered Federal News Radio’s survey volunteered plenty of ideas for improving their work spaces. Common suggestions included improving the lighting, ventilation and air conditioning. They also wished they had more freedom to get up from their desks.

“The pressure to have a butt parked in a chair for 9 hours straight is pretty intense. But a little bit of movement does wonders for my ability to focus,” said a Navy program manager in California who sometimes goes to the smokers’ hut outside to review materials. “I wish there was adequate space to stretch and flex every so often without feeling like I’m doing something wrong. For appearances sake, I will stay parked. But if productivity was the actual goal, I need to move around more.”

One Interior Department manager in Washington, D.C., who has their own private office, said they wished their employees had more access to sunlight. They also looked into purchasing standing desks for some workers with bad backs. Like the Navy worker, they said agencies should encourage employees to walk around more.

“I still think agencies should give ALL employees time during the day to workout/take a walk outside, something to get a break from workstations,” they wrote.

When designing its open headquarters, GSA tried to take employees’ considerations into account through rigorous studies of their work habits, said Kampschroer. It even counted employees’ work files to determine how much cabinet space they needed.

With regards to noise, which Kampschroer acknowledged is the biggest problem with open-space design, it tested acoustics in cubicles with walls of different heights. It found that people were the most respectful of their colleagues when they could see them.

GSA headquarters employees were among those who complained the loudest about their office setup in Federal News Radio’s survey. One compared it to a “call center environment.” Another said they felt like a “pack mule lugging your stuff to and from work” because of the lack of designated desks. Others said they left their desks to make phone calls so they wouldn’t disturb their coworkers.

Yet to hear Kampschroer describe it, one wonders whether the complaints about open-space design are just growing pains that will dissipate eventually. Moving to a new space is inherently disruptive, he said. It can help agencies that want to make changes.

“Disruption actually fosters change so sometimes it’s easier to make organizational changes—things that you’ve been trying to do—at the same time you’re moving into a new space,” he said.

And, while not the majority in Federal News Radio’s survey, some GSA employees made it known that they had adjusted to the change.

“It allows you to easily [collaborate],” wrote Sandra Hall, a contracting officer representative at GSA’s 1800 F St. headquarters. “You can see who is doing what or just faking it until they make it. It keeps down clutter because the space oftentimes is shared. It allows you to meet people you wouldn’t otherwise meet or work with for that matter.”

When Federal News Radio called Hall, she spoke in a hushed voice, perhaps because of her office mates. But, she said she thought a lot of GSA employees had made peace with the new design.

“A lot of people have already bought into it,” she said. “At first they didn’t like it, but now they do.”

The environment lets colleagues walk over to each other and talk face-to-face, whereas they might have worked by email or phone before, she said.

And that’s just what GSA had in mind when it redesigned the offices.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.