OPM’s innovation lab spurs new way of problem-solving

The sub-basement of the Office of Personnel Management's headquarters resembles more a tech start-up than a federal office building. The innovation lab, as OPM...

The sub-basement of the Office of Personnel Management’s headquarters resembles more a tech start-up than a federal office building. The innovation lab, as OPM calls it, provides a brightly-lit, open room for employees to meet and tackle the “stickiest” of the agency’s problems.

Beyond the new coat of paint and crisp white furniture, OPM is embracing innovation as a new methodology — the science of problem-solving. The approach is called human-centered design, and it focuses on keeping the end user in mind throughout the problem-solving process. Originally applied to product development, the human-centered design can also apply to services — like the ones federal agencies provide.

The hope is the new space and new approach to problem-solving will actually lead to a new culture — one of innovation in government.

“That’s not an oxymoron,” said Matt Collier, senior advisor to the OPM director and the head of creating the innovation lab.

OPM hired a consultant specializing in human-centered design. Pittsburgh-based LUMA Institute developed trainings and workshops for the agency. Also, 10 OPM employees — in addition to their full-time jobs at OPM — are now in a six-month program to be certified through LUMA as problem-solving facilitators.

These employees range in age, job and specialties, but all are “naturally gifted at facilitating,” Collier said.

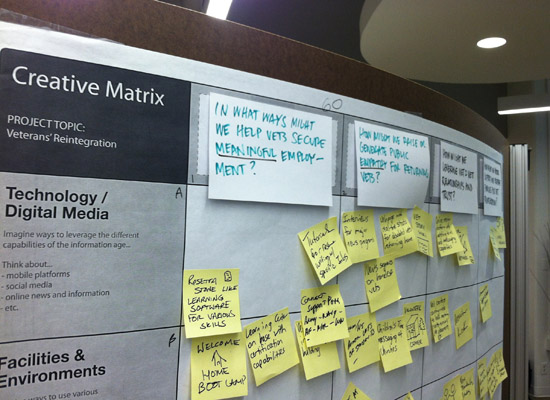

The institute’s methodology includes 36 techniques falling into three categories: Looking, understanding and making. Facilitators and stakeholders use a combination of the various techniques to attack a problem. Some of the techniques include making a map of stakeholders, doing a “fly-on-wall” observation of a product or service at work and creating quick prototypes.

Story continues below video.

|

Collier explains the transformation he sees in people who use OPM’s innovation lab. |

|

|

Picking the problem

The innovation lab’s facilitators vet projects before taking them on. They ask themselves three questions:

- Is the problem real, pervasive and long-standing?

- Are the stakeholders coming to the lab with the problem committed to solving it?

- What kind of impact will solving the problem make? Or, in Collier’s words, “How will the world be different as a result?”

One project currently underway is how to increase participation during open season, when federal employees can switch to a different health care plan.

“Once employees become more active, plans will have to propose more options, which will lead to competition, and we know competition can lead to savings,” Collier said. Put in context, in a $43 billion program, “even the smallest bit of optimization can produce significant savings,” he said.

Another project aims to improve the way OPM trains and integrates veterans into the federal workforce.

“The idea [before] was, ‘How do we make this training mandatory and make everyone take this?’ The idea now is, ‘How do we get the right training to the right people just in time?'” Collier said.

Ultimately, the success or failure of a project rests on those people who first came to the lab with the problem.

“The lab is only an enabling tool,” Collier said.

Rethinking office space

Part of that enabling function is simply to provide a place where people can meet. What’s special about the lab’s space is it wasn’t constructed simply to look cool — designers deliberately incorporated features that would increase collaboration in the $750,000 remodeling project.

Collier contrasts the lab to the traditional office workplace. You go into a conference room with a rectangular or U-shaped table, and the people with power sit at the head. In this set-up, the people in power drive the conversation and are “forcing people to settle on what the problem is, let alone how to solve it,” Collier said. “That’s what’s got us into the mess that we’re in today.”

In the lab, employees can have a “plenary” session in the middle of the room and then quickly break up into groups, easily rearranging the wheeled tables, chairs and even the whiteboards, “without losing sight of people and without losing the energy and the momentum of the session,” Collier said.

Different-colored Post-It notes cover one whiteboard while another displays a map of stakeholders in the Presidential Management Fellowship, with arrows crossing from one group to another. A far corner resembles a living room, with a couch and TV monitor.

The overall look and feel of the space also triggers “cues” for employees to think differently, Collier said.

Take the example of two OPM offices that had “long-standing tension” between them and could not even agree on an agenda. The lab gave the two offices an excuse to meet, and the non-traditional look of the space “broke down the traditional barriers” between the two groups, he said.

|

|

Innovation in government is

|

“I’m not going to lie. It was rough at first. They were talking past each other,” Collier said.

But by the end of the hours-long session, the two offices were talking to each other.

Innovation lab’s ‘spillover’ effects

On a recent afternoon, senior executives sat on a stage in OPM’s auditorium. But instead of making the presentations, SESers were listening to employees present their ideas about how to make the agency work better. One OPM employee teleconferenced in, while another came onstage with a Prezi presentation. OPM spokesman John Marble likened the meeting to the TV show Shark Tank, where entrepreneurs have a chance to present their ideas to potential investors.

The meeting is just one of what Collier hopes will be many examples of innovation seeping into the workplace culture.

Such a cultural change will be difficult to measure. But a July report from the Partnership for Public Service found OPM had made the greatest improvements on innovation compared with all other federal agencies, based on the Federal Employee Viewpoint survey. OPM’s biggest boost came from people agreeing with the statement, “I feel encouraged to come up with new and better ways of doing things.”

The innovation lab — and Collier refers to the lab as both the physical space and the problem-solving methodology — has clear outputs. The teams that meet there have a clear problem to solve and walk out, hopefully, with some solutions to try out.

“Another less tangible output is the fact people have come through here. They’ve experienced the space, they’ve experienced the methodology, and, ultimately, they go back to their home organizations … and to the extent this is shifting mindsets, that’s what’s creating those spillover effects,” Collier said. “Let’s say they’re in a staff meeting. They can think a little differently about how to approach and define a problem, and how to solve it.”

RELATED STORIES

Report: Lack of encouragement causes agency innovation to fizzle

Federal CTO plans new networking tool to spur innovation

Five innovation projects win governmentwide ‘bake-off’

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.