With all of the mandates and threats, should companies really “want” federal contracts?

Between COVID-related mandates and burgeoning cybersecurity requirements and False Claims Act threats, is it still worth the trouble for companies to try and ob...

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

Between COVID-related mandates and burgeoning cybersecurity requirements and False Claims Act threats, is it still worth the trouble for companies to try and obtain federal business? Well there’s an irony here: if you are in fact secure, and you’ve got the best mousetrap, a contract is more important than ever. For one expert take, Federal Drive with Tom Temin turned to federal marketing and sales consultant, Larry Allen.

Interview transcript:

Tom Temin: And Larry, you have written that you need a contract. But why would you want a contract, given how hard it is to do business seemingly with the government these days? So what gives here?

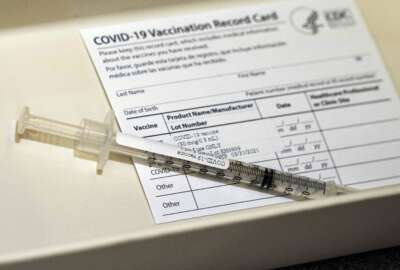

Larry Allen: Tom, it’s a little bit of a dichotomy in the marketplace. In my experience, you absolutely do need to have a contract in order to be able to sell. You need to be able to answer that how question with the government agency. So whether it’s a prime contract that your company holds, or the ability to sell through somebody else’s contract, either as a subcontractor or a commercial item supplier, you need to be able to have that contract access, because otherwise you’re going to be at a real competitive disadvantage when going to market. I’ve seen that over and over again, where companies think they have the absolute best mousetrap. But if your mouse trap is a little bit more difficult to get to than some other pretty good, mousetraps, busy contracting officers, busy federal agencies might just go for the pretty good because it’s easier to get to rather than your solution. On the other hand, holding a contract — and really, to be honest, aid from being a subcontractor — now poses more burden for contractors than any time in the last 10 years. New rules keep coming down all the time, and they’re not all even out yet. So we know that there are things about supply chain security management, on cybersecurity model maturity certification. There’s requirements for now vaccine mandates. It all adds up, Tom, it all adds up to significant cost for contractors, not just to comply, but to even find out about what some of these requirements are, and then put the practices and policies in place to make sure that they follow through. And for smaller, medium sized businesses, that can be a prohibitive cost. So that’s why I’m writing about it. It’s time to evaluate this whole idea of a contract. I know I’ve got clients that are thinking, gee, do I really need this headache? And ultimately, the answer is yes, if you want to be part of the federal market.

Tom Temin: Yes, because there is another irony here, too. And that is it can be more costly to do business with the federal government. And yet, for many companies, especially those in the product area, the government expects the best possible lowest price that you offer anybody else on the presumption that the government is always your biggest customer. And so you may have lesser margins, if you’re not careful in dealing with the government.

Larry Allen: This is a discussion I’ve absolutely had with some of my businesses lately, Tom, particularly smaller firms that tend to be more product based. And what I’m telling them is, look, when you’re looking at this deal, yes, the top line numbers seems like it’s really intriguing. But you have to ask yourself, what’s the margin? How many resources are you going to be dedicating to pursuing this lower margin business, versus some other piece of business that you could pursue, that maybe has some services attached to it, or maybe it’s going to be somewhat more complex anyways, so that you get that better margin, so it’s worth more to you? Look, if you’ve got $150,000 task border, but your margin is going to be 2%, you probably would rather pursue $125,000 piece of business, or you could get a 5% or 6% margin. I’m not very good at math, Tom, but it does add up. And you have to consider that. You have to consider where you expend your resources. But it also all gets back to the question of, alright, I’m thinking about this business, I am a smaller business. I’ve got this other new rule that I’ve got to require. And if I’m selling products, I’m thinking about the new Made in America rule that’s gonna affect the Buy American Act. How does that impact my business? Businesses are asking lots of questions. And what I suspect we’ll see is an exodus of companies that either can’t or won’t comply with some of the requirements. And you see that happen every year, Tom. But you know, if you start to lose some critical partners for the government, that’s a risk to government too. So it’s not like you can keep loading things up on one side of the scale. Eventually, if the relationship gets too out of balance, it’s going to impact the agency, too.

Tom Temin: We’re speaking with Larry Allen, president of Allen Federal Business Partners. And among the new risks for contractors is — as you have pointed out, and we’ve spoke to others on this point — the False Claims Act now is being invoked by the Justice Department as something they will use against companies that say they’re secure according to certain NIST standards. But if there’s a breach and they’re found to have not been totally compliant, then you will have been as a company guilty of False Claims Act violation. And just outline for us how expensive that can actually be.

Larry Allen: Tom, False Claims Act violations can be very expensive. And I’m not at all surprised to see the Department of Justice using this as a tool to drive cyber compliance, particularly surrounding systems a contractor might have that handle sensitive government information. Let’s start with the per invoice fine, because every invoice that you submit is considered a separate false claim. The False Claims Act allows for a fine every time you submit a false claim. And the numbers are a little odd, they’re a little off, Tom. But generally they’re in the $11,000 to $24,000 range, per invoice. So if your company submits 20 invoices before you realize that there could be a problem, right away the calculator’s gonna start adding up on the per invoice fine. There’s always the recovery, Tom, those are the amount of damages that the government thinks it’s entitled to. But the False Claims Act takes those damages, and multiplies them by three. So if the amount of overcharge that the government claims you had was 100,000, it’s really 300,000. So you’ve got the per invoice fine, the recovery and the treble damages. And Tom, that’s even before we get into lawyer costs, lost productivity. Hopefully, you have enough sense to hire a really good outside consultant. That’s money well spent. But you can see the False Claims Act is not something that contractors should take lightly.

Tom Temin: The bringing of a False Claims Act violation charge would then come via the contracting officer? So in many cases, that’s where the rubber meets the road. Companies, I think, are more liable for false claims with respect to pricing, for example, than they might be for cybersecurity, which can be a fairly subtle area to decide whether something that you said about your cybersecurity is in fact false. And I’m just wondering if contracting officers are going to be looking for that kind of thing. Or if they figure as long as nothing goes wrong in a cybersecurity sense, they’ll leave well enough alone, or are these charges likely to come from another vector like a whistleblower?

Larry Allen: Tom, and it speaks directly to where a lot of the larger dollar False Claims Act cases come from. And while it’s true that an audit or contracting officer on the government side could flag a potential problem that leads to a False Claims Act matter, most of the larger False Claims Act matters are whistleblower cases. So it wouldn’t necessarily be the contractor. It probably would be a disgruntled competitor — somebody who says, I know darn well this company doesn’t have the cybersecurity standards in place that it needs, it bid on this contract, it’s in violation because it can’t meet that requirement. I’m filing a whistleblower suit under the qui tam provisions of the False Claims Act. That’s really where a lot of these come from. And of course, there’s a huge financial incentive to file them. You know, first of all, you’re dinging a competitor who’s not going to be at a disadvantage. But second, if the government collects damages, you as the whistleblower get to keep part of that. So you know, if your third quarter is flagging, then yeah, that may be something people consider.

Tom Temin: So in other words, these types of charges then typically come from vectors you’re probably not aware of, deep within the bureaucracy.

Larry Allen: Particularly in a False Claims Act case, regardless of who files it, If it’s a whistleblower case, Tom, it’s usually filed under seal. And you, the company, might even not know that you’ve got a problem. The first hint of a problem would be an audit letter that comes out of the blue, not during any regular renewal cycle. That’s when it’s time to really sit up and take notice, call your lawyer, make sure that you’re doing the internal reviews you need to do to find out what somebody thinks they found.

Tom Temin: Alright, so federal market still a worthwhile thing to pursue, but you got to be really careful.

Larry Allen: That’s exactly right. The best prepared contractor is the one that’s going to be most successful, Tom.

Tom Temin: Larry Allen is president of Allen Federal Business Partners. Thanks so much,

Larry Allen: Tom, thank you and I wish your listeners happy selling.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Tom Temin is host of the Federal Drive and has been providing insight on federal technology and management issues for more than 30 years.

Follow @tteminWFED

Related Stories

Contractors assess the just released details of White House COVID-19 protocols