The Naval Criminal Investigative Service has reopened a criminal investigation into the operation of an off-the-books law enforcement agency at Norfolk Naval...

The Naval Criminal Investigative Service has reopened a criminal investigation into a long-running scandal involving the operation of an illegitimate police force at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, rekindling the possibility of criminal prosecutions in a case in which investigators allege $21 million was wasted and more than $4 million in property remains missing.

The 12-year episode, details of which were first made public by Federal News Radio in August, involved the improper acquisition of weapons, vehicles and police and military gear by managers of an internal security unit that was not authorized to carry guns or perform law enforcement functions.

Most of the employees involved have retired and none have been prosecuted or punished thus far, but NCIS formally reopened its investigation on Sept. 21 after having closed the criminal probe three years earlier.

Documents obtained by Federal News Radio in response to a Freedom of Information Act request to Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) show that NCIS initially investigated the case in 2014, but was not able to convince an assistant U.S. attorney at the time to authorize grand jury subpoenas or move forward with criminal prosecutions.

A government official knowledgeable about the details of the investigation said the criminal case that was presented to prosecutors at that time focused primarily on the security specialists’ acquisition and use of police badges. NCIS zeroed-in on that aspect only because investigators believed it represented the clearest evidence that the security division — a group of about 50 unarmed civilian employees designated “Code 1120” — had violated federal statutes, in this case, those against impersonating law enforcement officers.

The group allegedly “handed them out like candy,” including to people who did not even work in the security division, including base public affairs staff and senior installation managers. They also allegedly ordered and distributed “retired” badges.

The official, who was not authorized to speak publicly about the case and requested anonymity, said witnesses told investigators at the time that at least one of the motivations was so that badge-holders could take advantage of the Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act, a federal law which permits active and retired police to carry concealed firearms in any state, irrespective of state law.

“If you have a badge and credentials and you’re carrying a concealed gun, most law enforcement officers you might encounter are going to say, ‘No harm, no foul,’ because no officer knows what every [legitimate] agency’s badge looks like,” the official said. “So that was at least part of the reason for all this.”

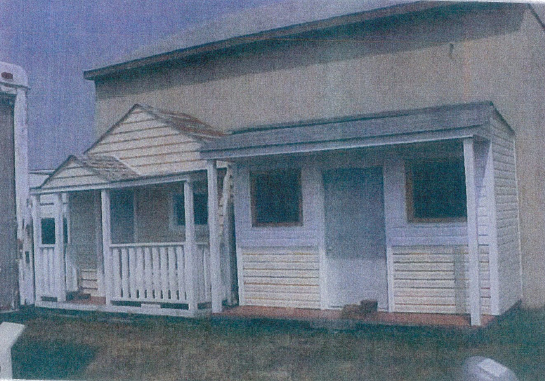

Building facades the team constructed for “building entry” training scenarios.

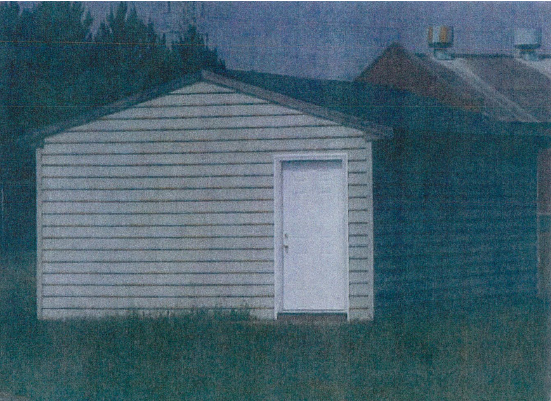

A portable “kill house,” which the security department said was to be used for “close quarters combat training.”

This Navy personnel carrier had “police” emblazoned on the side, despite the fact that the unit operating it was not an official law enforcement team.

A high-speed interdiction boat was bought for $150,000 with a government purchase card, and the team paid at least $206,000 more to tie it up at a nearby private marina instead of at the shipyard itself, where there was abundant dock space for small boats.

The documents NAVSEA released last week are part of an administrative investigation the command conducted in 2014. They are heavily redacted, but offer a detailed accounting of the other equipment the security group obtained without any authorization or legitimate mission need, including hundreds of vehicles ranging from Humvees, to tractor trailers, to backhoes and SUVs, a private armory of unauthorized firearms and ammunition, and an armored personnel carrier the group repainted in black and labeled “Police” on its sides.

The investigation, conducted by the NAVSEA inspector general, said most of the vehicles and other equipment were acquired as surplus property from the Defense Logistics Agency’s Defense Reutilization and Marketing Office (DRMO) at St. Julien’s Creek, a nearby Navy annex, and had a total value of $8.8 million.

Most of the equipment the security specialists took from the DRMO facility had a logical connection with the off-the-books law enforcement organization they seem to have been trying to build. In other cases, not so much. For example, they also checked out 9,810 “extreme cold weather parkas.”

But hundreds of thousands of dollars in other unnecessary and unauthorized purchases, for items such as night-vision goggles, handguns and a “luxury” high-speed pursuit boat were bought outright using government purchase cards, the report said.

In all, $4.1 million worth of the equipment — mostly made up of vehicles obtained from DRMO — remains unaccounted for.

The 2014 NCIS investigation did not attempt to build a criminal case based on the missing vehicles, partly because the lax oversight and recordkeeping procedures that let security employees easily obtain them from DLA in the first place also made it nearly impossible to track them or conclusively prove where they wound up, the official said.

Other evidence and testimony shows that the security workforce often drove the vehicles home after having outfitted them with police lights and sirens. Some of them bore fictitious license places that the security staff moved from vehicle-to-vehicle or manufactured on their own, since the Navy’s Facilities Command (NAVFAC) refused to sanction or license them.

They also worked diligently to shield the vehicles and other property from view, fearing that the unauthorized equipment might be taken away, the NAVSEA investigation found.

Despite that, one of the shipyard’s internal auditors began to notice sometime in 2011 that the 1120 employees seemed to have numerous undocumented vehicles in their possession that they could not justify. Based on its mission, the security department was only authorized to have the small sedans it leased from NAVFAC.

The yard official “believed that it was illegal to stockpile the property and that, if it was not being used, the requirement was to turn it in.” After the group was told in no uncertain terms that it would have to get rid of its unauthorized fleet, the same auditor returned for a follow-up visit later in the year and concluded it appeared “that vehicles were being moved around to give the impression that they had been returned.”

Besides the vehicles, the 1120 group had good reason to fear that the law enforcement equipment and weapons they had collected would be taken away if they were discovered. That’s because clearly-articulated Navy policy in place since at least 2003 says that the Navy Police Department is the only organization that’s allowed to act as an armed law enforcement force at the service’s bases, absent a specific waiver from the Chief of Naval Operations.

“The intent was to establish a police force within [the security department] at some point down the road” after seeking CNO approval, one unidentified 1120 official said during an interview with investigators. But formal permission was never requested nor received, and investigators say the officials conceded they could point to no evidence of inadequate protection by the legitimate Navy Police.

In addition to $10.4 million wasted acquiring various property, the IG concluded the security department misspent another $10.6 million on personnel.

Investigators said the manpower estimate was only a ballpark figure, partly because they could not account for several of the 1120 employees’ actual work activities for the previous five years. The $10.6 million estimate is based on comparisons with the size and spending of the security workforces at the Navy’s three other public yards.

The Norfolk yard, the IG said, had used the unusual authority it had to approve its own budget to balloon its workforce to twice the size of any of the other yards, “both in terms of total personnel and the number of high-graded employees.”

Some of the misspent funds went toward what the investigation deemed unnecessary law enforcement training, including at the government’s Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, the Georgia facility most federal law enforcement agencies send their agents to.

In explaining why those expenses — including some for narcotics investigations — were authorized, one 1120 official told investigators he didn’t see it as a problem that the courses had no connection with the security department’s actual duties, and that part of the goal was to help employees build individual development plans (IDPs) that helped them get their “dream jobs” in the government.

“So, for an example, if I had somebody that said, ‘Hey, my goal is to [get a job with] the Border Patrol, and I think I need to go learn Spanish,’ we were supposed to at least see if that was a possibility,” investigators quoted the manager as saying.

Asked whether astronaut training for a security specialist would have also been acceptable: “Well, if your IDP had your dream job as the astronaut for the government, so I guess NASA — I think

they’re government employees — then, yeah.”

NAVSEA heavily redacted its investigative documents before disclosing them to media organizations. Many of the report’s findings and recommendations were blacked out, as were the names of all of the witnesses and the subjects of the investigation.

But multiple sources said the investigation centered on at least three individuals: Mark Perry, a former deputy director of security; Glenn Hawthorne, a former security director; and Rob Marcum, another employee who investigators believed was primarily responsible for obtaining the vehicles from DRMO and serving as a “wrench turner” to outfit and maintain them.

Even if none of the security group’s activities amounted to criminal activity, the NAVSEA IG concluded they were only one piece of what it deemed of a culture of mismanagement and poor oversight at the Norfolk Shipyard.

The report alluded to another investigation NAVSEA had concluded at the same yard earlier in 2014. Its existence has not been previously disclosed and the report does not describe the findings in detail, but investigators substantiated 14 other previous allegations relating to wider management issues, including:

Those prior findings made the matter of the unauthorized police force all the more troubling, the IG wrote, suggesting it was part of a pattern of near-nonexistent oversight by a series of seven different uniformed shipyard commanders.

“The timing, coupled with the sheer scale and volume of the violations raise serious concerns about management oversight, specifically, how the violations were permitted to occur over the span of 11 years without senior leader intervention,” the report said. “Although the lack of senior management engagement and oversight may not have risen to the level of a violation of law, it highlights the leadership environment that has existed under multiple NNSY Commanders and among senior NNSY leadership.”

In a statement to Federal News Radio, NAVSEA officials said they had taken a series of steps since 2014 to rectify the issues the IG identified at Norfolk.

As to property accountability, officials said they had barred any employees from the shipyard security department from checking out any more property from DLA’s DRMO facility, adding that the IG conducted another thorough audit of the security department in 2016 and found that it had become a “model organization” by that time.

“All administrative personnel actions, including letters of caution, oral reprimands, briefs, and retraining in areas such as time and attendance, purchase cards, procurement authorizations and the DRMO process have been completed,” Alan Baribeau, a NAVSEA spokesman, said in a statement. “The shipyard also overhauled its asset management program, which was recently recognized as the model program by NAVSEA, and completed all required actions stemming from the investigation. This included conducting a full inventory of all remaining assets and reducing the assets controlled by the security office.”

As to the $4.1 million in equipment that remains unaccounted for, “The Command Evaluation and Review Office will pursue any future leads regarding missing items as they come to light,” the statement added.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jared Serbu is deputy editor of Federal News Network and reports on the Defense Department’s contracting, legislative, workforce and IT issues.

Follow @jserbuWFED