INSIGHT BY BELCAN

Building Adoption Of Cyber Security Practices – Crafting Cyber Culture

People are the biggest risk to the security of information technology environments: Individual users being socially engineered, complex human-run organizations that...

This content is sponsored by Belcan

Author: Jas. Powell, CTO- Enterprise IT

The Problem

People are the biggest risk to the security of information technology environments: Individual users being socially engineered, complex human-run organizations that are slow to adapt, and inconvenient rules and regulations in a world where marketing to convenience sells big. The greatest cyber security threats leverage our human failings and oddities of our culture to create pervasive and massive gaps to our defensive posture. Some proven ways to combat this involve building adoption of cyber practices into our culture. We can create opportunities to positively influence our people and processes through enabling a culture built around security. Let’s look at why people are the part of the problem, then we can examine some techniques to increase adoption of sound security practices. Once we understand the biggest risk, we can have the greatest impact by understanding how to leverage cultural adoption to increase the impact of security policies and procedures.

Speed Limits

Let’s examine the concept of speed limits. Bear with me here, we’re going to apply this to security and culture, I promise… Speeding is a major contributor to traffic collisions and can cause property damage, injury, and loss of life. Yet we do it anyway. I don’t know anyone who is committed to always restricting their speed to posted speed limit signs. In the metropolitan area where I live — even in areas where there are known speed cameras — if you aren’t going at least 5 MPH over the speed limit, there’s a likelihood that the car behind you will tailgate you out of sheer frustration. We have such disregard for speed limits that even when it is photo enforced by a robot, we are expected to go as fast as we can without getting caught by the camera. Part of my commute through Virginia includes a pace of traffic that exceeds 80 MPH on a road with a speed limit of 55 MPH. (In Virginia, driving 20 MPH over the posted speed limit is ticketed as Reckless Driving, which carries a $2,500 fine and 6 points.) As a culture, the risk of damage, bodily harm, or monetary fine are preferred to driving the speed limit.

In residential neighborhoods, the story can be quite different. For example, in the neighborhood where I live, the 25 MPH speed limit is more successfully enforced. This is because the culture of the neighborhood includes loud and often public shaming of anyone speeding to or from one of the homes (usually by people walking their dogs or specific neighbors who keep an eye out and will then come knocking on your door). The speed limit within the neighborhood has been culturally adopted. The system works. Neighbors are motivated to operate within the speed limit by the social implications of rule-breaking rather than by potential financial ramifications imposed by the law.

Relating to Information Technology

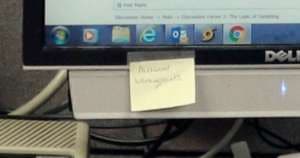

Recently there was a photo released by Hawaii’s Emergency Management Agency of an employee, and next to him was a password written on a piece of paper stuck to a monitor. The proper handling and management of passwords and system access has not been culturally adopted. As much as we shame or chuckle at those who do this, after more than 20 years of working in IT, I see the practice continue. Part of this I realize is the IT adage, “complexity adds risk,” or the old-school idea of relying on physical-layer security — and those beliefs are not always wrong. Managing the risk of a complex shared password within a secure space to a system that’s deprecated — or to which access management is difficult — isn’t always completely wrong. Taking a photo of it is. Layered access control is best, but managed risk has its place. As a security nerd though, a PSK (Pre-Shared Key) is the same thing as no key at all. It’s more of a door handle than a door lock. If there’s a rule that reads, “don’t write down your password,” it’s a sure indicator that at least someone is not paying attention to it.

Recently there was a photo released by Hawaii’s Emergency Management Agency of an employee, and next to him was a password written on a piece of paper stuck to a monitor. The proper handling and management of passwords and system access has not been culturally adopted. As much as we shame or chuckle at those who do this, after more than 20 years of working in IT, I see the practice continue. Part of this I realize is the IT adage, “complexity adds risk,” or the old-school idea of relying on physical-layer security — and those beliefs are not always wrong. Managing the risk of a complex shared password within a secure space to a system that’s deprecated — or to which access management is difficult — isn’t always completely wrong. Taking a photo of it is. Layered access control is best, but managed risk has its place. As a security nerd though, a PSK (Pre-Shared Key) is the same thing as no key at all. It’s more of a door handle than a door lock. If there’s a rule that reads, “don’t write down your password,” it’s a sure indicator that at least someone is not paying attention to it.

How we craft passwords is still broken. Culturally we understand that the current way we use passwords is insufficient still we continue old practices. The concept of a passphrase hasn’t quite reached as far as it should. How many systems don’t allow spaces in passwords or have a character limit while forcing the use of numbers and special characters? Lots. It’s easier to memorize and manage >14-character passphrase than it is 8-characters of ASCII gobbledygook. When users are forced to change passwords often, how many simply iterate them with a 1 or 2 at the end? Too many. Use of passphrases is not only not well adopted, but not even uniformly enacted.

Ten Most Common Passwords

1) 123456

2) 123456789

3) qwerty

4) 12345678

5) 111111

6) 1234567890

7) 1234567

8) password

9) 123123

10) 987654321

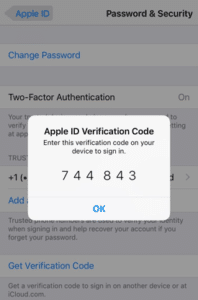

MFA (Multi-Factor Authentication) is gaining ground, but not fast enough. I love when systems default to MFA (see also TFA or Two-Factor Authentication). Just last month, I signed up for a web-based service and they sent to me a password in the body of an email, not encrypted or obfuscated in any way. This should not be happening in 2018. I must give credit to Apple and Google for really leaning into MFA in the consumer space. Well-populated services getting behind this is a great leg-up on cultural adoption of a smart security practice.

A security practic e that has not been either culturally adopted or technically enacted: Emails that contain HTML links. Do you click on it? Up to 45 percent of people are fooled by phishing attacks that use links in emails this way. Outside of the common practice of a user-triggered and expected password-reset or account sign-up email that contains a one-time use link, it is a great pet peeve of mine when companies send internal emails that include a link to an external site. Nope, I don’t care if it’s companyname.somewebservice.com. An unsolicited link in an email is not a good idea. If you’re curious how link scan be used to infiltrate and steal information, check out this article from TipTopSecurity on how it’s done. Every time it’s legitimately used to speed some internal process, it serves also to validate the practice of phishing. For me, the cyber security practice of never clicking on links within an email should be spread to the point that if an email contains a link it should lead directly to a phone conversation. “Did you just send me an external link? Why would you do that? I’d never click on a link in an unsolicited email!”

e that has not been either culturally adopted or technically enacted: Emails that contain HTML links. Do you click on it? Up to 45 percent of people are fooled by phishing attacks that use links in emails this way. Outside of the common practice of a user-triggered and expected password-reset or account sign-up email that contains a one-time use link, it is a great pet peeve of mine when companies send internal emails that include a link to an external site. Nope, I don’t care if it’s companyname.somewebservice.com. An unsolicited link in an email is not a good idea. If you’re curious how link scan be used to infiltrate and steal information, check out this article from TipTopSecurity on how it’s done. Every time it’s legitimately used to speed some internal process, it serves also to validate the practice of phishing. For me, the cyber security practice of never clicking on links within an email should be spread to the point that if an email contains a link it should lead directly to a phone conversation. “Did you just send me an external link? Why would you do that? I’d never click on a link in an unsolicited email!”

Maybe I’m over-cautious, but until email systems can completely and reliably scrub external links from emails, the practice of sending unsolicited links within emails should be shunned. HTML is a good protocol for formatting, displaying, and connecting information, but it has not moved with the times. The ability to leverage scripting and other capabilities has exposed more avenues for abuse and intrusion. Using something that allows such high risk within something so ubiquitous and critical as email is troublesome. Our anti-phishing stance of, “just don’t click on external links,” hasn’t come close to limiting the behavior. Not at 45 percent. Here the neighbors are yelling at us to stop, but almost half of us don’t. A positive step an organization could take is to manage internally hosted referral links and never allow external links in emails. Not perfect, but sets a better expectation for users to not trust external links targets that haven’t been vetted. Unfortunately, this is not a common practice.

How to Build Cultural Adoption

We’ve gone over some practices that have had trouble catching on, some things that are working but need help, and some that are catching on. While humans remain biggest risk factor and we can help create better cyber-citizens. Here are some broad guidelines on getting to a more successful implementation of cyber security practices trough cultural adoption:

- Empower the positive – Tom Mendoza, one of my all-time favorite thinkers and speakers, famously crafted the initiative Catch someone doing something right. Actively appreciate actions and behavior that is right and correct. Need not be leadership driven, but top-down enthusiasm for the positive drives culture like nothing else. More carrot than stick.

- Enable shame – There are two sides to every coin, and a raised eyebrow from a peer when you’re seen avoiding a security practice can be effective. Encourage through example and conversation the responsibility to observe practices and be involved. Walk away with your screen unlocked, get the full Spock eyebrow. Tailgate without badging-in, get a nicely sarcastic, “Really?…” What’s a carrot without a stick?

- Success and measurement – Many CISO organizations will send mass emails about new threats or precautions, but does your organization provide any messaging on how well your company is doing? What was measured and where is your company based on previous data. Who doesn’t like a good graph that shows a trend?

- Training, testing, gaming, fame – Training is good. Testing is better. Simulation is best. Having a scoreboard is epic. Execute corporate training on security, but include both testing and company-sponsored or contracted simulated phishing attacks and data breaches. Most importantly, post a scoreboard on who did best. Indulge the human competitive spirit and publicly laud those in the top 100.

- Fatigue and complacency – This is a tough one. The more breaches we hear about makes us both tired of hearing about them and emotionally numb to their inevitability. These incidents and warnings need to be brought to our attention with fresh perspectives (e.g. this article) with an eye on the complacency problem. Hypothetical examples, case studies, and telling what-if stories can help here. If you lecture someone, they might listen, but if you tell them a story, they want to be a part of it. Humanize and use narrative.

- Write a catchy tune – Actually no, don’t do that. I still have that 1-877-Kars4Kids tune stuck in my head from the late 90’s. Let’s not.

- Encourage personal adoption – Instead of only dictating new security guidelines, include reasoning as to why the new methodologies can also protect employees’ personal information at home and on the internet. This is another good place for narratives, nothing inspires change better than personal impact.

- Drive personal responsibility – Nothing hurts like a punch in the wallet. Giving each employee a quarterly MBO crafted around compliance and participation. What percentage bonus might it take to motivate a practice that will eliminate a risk that could cost a great amount of money, faith, or real security? Or we stick with the standard, “The beatings will continue until morale improves…”

Take Action

Treat each new rule, policy, or threat mitigation as an opportunity to make a successful and enduring impact. Leverage cultural adoption as a major part of every communication and implementation plan. Communicate successes and trending progress. Don’t just post a sign and let a robot watch people speed by: Get the neighborhood involved or else, risk property damage, injury, or significant monetary impact from security breaches. Or I guess, just go slow and irritate everyone.

Let’s continue the #cybersecculture conversation on Twitter, tag me @JasPowell

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.