How the National Security Council could better deal with technology-based threats

A study sponsored by the Brookings Institution has several recommendations for reforming the National Security Council, reforms its urging the Biden administration...

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

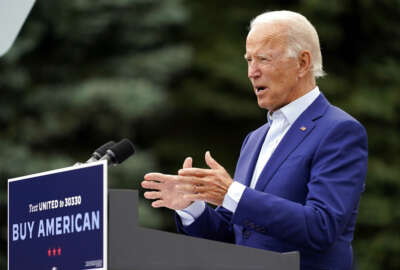

Threats to the United States have, increasingly, a technology component. That’s because the nation is ever more dependent on information technology for daily life at work and at home. Now a study sponsored by the Stanford Center for International Security and Cooperation and published by the Brookings Institution has several recommendations for reforming the National Security Council, reforms its urging the Biden administration to make. With a summary, study co-author Zoe Weinberg joined Federal Drive with Tom Temin.

Interview transcript:

Tom Temin: Ms. Weinberg, good to have you on.

Zoe Weinberg: Appreciate it Tom, thanks for inviting me.

Tom Temin: First of all, give us the sense of the background here. I mean, technology has always been part of national security threats, I guess, ever since the Soviets developed their own atom bomb. So what’s different today?

Zoe Weinberg: Tom, we find ourselves today at a point in history in which the nature of conflict is shifting so profoundly that in many ways our old tools for understanding the challenges are just misaligned with the new reality. Today, technological control, surveillance, information, access — those have really become the weapons in this next era of conflict. And we’re already seeing this play out in the form of cyber attacks, the spread of disinformation, stolen intellectual property, and the subversion of democratic institutions via social media. You’re right that, of course, technology has long played a part in shaping the security landscape. And I do think that leads some to say maybe there’s nothing new here. And to some extent, I think there’s truth to that. But in this case, the scale, the velocity, the extent of technological development is really unprecedented. And unlike in the past, many of these technologies today are widely available to the public. They’re not developed in a classified setting or military setting. So it’s both a moving target and the risks are pervasive.

Tom Temin: Let’s talk about the National Security Council for a moment, because I’m not sure people know exactly what it does except sit around and meet, and then everyone goes and gets a great consulting job when they leave.

Zoe Weinberg: So the National Security Council, the NSC, is widely considered the most powerful decision making body inside the executive branch’s security apparatus among those who are sort of government insiders. It’s charged with advising the President on military strategies, statecraft, diplomacy, and it’s responsible for coordinating between all of the government’s different intelligence and defense bodies. Brent Scowcroft, who served as national security adviser for Presidents Ford and Bush is really credited with creating the modern day NSC and positioning it as an honest broker of sorts among all of the other security related institutions.

Tom Temin: Okay, I was gonna say once every ten times they actually get things right too, so I guess you’re betting pretty well. In its present form, you are arguing that the NSC is not quite structured in the best way to take on this new technologically based, and as you point out, it’s not just coming from one or two countries, but it’s broadly available, these threats that can be aimed at anywhere by anybody, and the NSC isn’t really equipped to take on that challenge. So you’ve offered a couple of choices for how this might be remedied. Let’s talk about how the council itself could be reformed.

Zoe Weinberg: Tom, there are a lot of changes that are currently in motion in the new administration. So I think it would be a bit premature to comment there, as I suspect we’ll be learning more in the coming weeks and months and don’t currently have a full picture. But you’re right, historically, know that the NSC has not been configured to take on these challenges. We spoke to over 25 NSC staffers, other policymakers, academics about the subject, and all of them said that the NSC hadn’t quite gotten it right. And so we’ve offered sort of a menu of different possible reform options. The NSC in general is organized into different directorates that are focused on different regions or issue areas. Under the Obama administration, a new cyber directorate was created, and that was a great first step. But there’s a lot of technology related security threats that are not cyber threats. And a lot of the people we interviewed told us that efforts to cover those non cyber topics could be quantum or blockchain often end up being taken up on on more of an ad hoc basis. There also wasn’t enough technical expertise on staff. And there were few ways to sort of systematically compare notes with the private sector. So oftentimes, issues slip through the cracks.

Tom Temin: Alright. So the idea of a new directorate for the non cyber type thing, though that adds complexity then too, doesn’t it?

Zoe Weinberg: It does. We sort of thought that it was important to start from first principles and really think about what should these reforms be trying to accomplish before just creating new entities and new positions. We came up with a handful of criteria, some of which I’ll share, but one is, ensuring that the White House recognizes the urgency of emerging threats from technology. The reality is that it’s hard to maintain focus on these issues. The NSC is often fighting fires every day dealing with the most pressing security issues, whatever is making headlines on the news. And often these technology risks are looming on the horizon, they don’t always present as the most urgent. So we thought it was important for the structure to reflect a real intention to ensure that these threats don’t get lost or deprioritized. The other things we hoped that a reform would accomplish would be about bringing tech expertise to bear on these challenges, and also ensuring good coordination at both the White House and the interagency level.

Tom Temin: And then the other kind of basic policy option that you offer is to increase the threat dealing capability at the federal agency level. And somehow, then that could be coordinated through the National Security Council, but there’d be more muscular ability spread throughout the government. Describe that option for us.

Zoe Weinberg: So another strategy for incorporating emerging technology into security decision making would be to focus on building expertise across the executive branch. And in that case, maybe the NSC would occupy more of a supporting role rather than taking the lead. So under this more decentralized approach, the center of gravity on particular issues would really sit in specific departments and agencies with relevant expertise, which would allow for some ground up coordination, and may ultimately improve connectivity between the NSC and the agencies.

Tom Temin: Yeah. And then when one agency is hit that would maybe know what to do, and you wouldn’t have this scramble that we seem to have every time something goes wrong.

Zoe Weinberg: Yep, I think that’s right. And they’re also not mutually exclusive reform options. I mean, you could argue that in one approach, the emphasis is sort of on top down leadership, and on the other, it’s bottoms up. But it is possible to enact reforms along both lines, and they are complimentary

Tom Temin: in calling for a holistic review of the National Security Council, the question is whose best to do that because very few organizations are really good at assessing themselves. Is this something that Congress should undertake? Or should there be some kind of external commission to look at this? Or how do you you get the ball rolling here on reforming something like National Security Council?

Zoe Weinberg: The National Security Council itself and its configuration, there’s a lot of leeway in the White House itself. There’s only sort of limited congressional direction or guidance on the shape in the form of the NSC. So it really is the White House that’s in the best position to sort of think about how to reconfigure it. That being said, there have been efforts across government to think about how we might best position ourselves to tackle different technology areas. I worked for a period on the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, which is doing just that type of analysis, specifically for AI, but looking both at the agency and department level, as well as looking at the White House.

Tom Temin: And the interesting irony here is that the types of threats that the NSC is most capable of dealing with have actually never occurred, say, nuclear attack or some kind of a frontal attack on the United States, maybe 9/11, but that was one time in, what 75 years, whereas the issues you’re dealing with now, cyber attacks, but beyond cyber as you point out, theft of intellectual property, that kind of thing happens daily.

Zoe Weinberg: It happens daily, and it happens both against the public sector, but also in the private sector. So whereas nuclear threats are sort of limited to state conflict, I think what we’re seeing with new technology is that the threats are increasingly diffused, they’re privatized, they are transnational, they are both impacting and are executed by civilians, and that sort of equal pace. So it is a very, very different and complex security landscape.

Tom Temin: So in some ways, 9/11 is a pretty good model when you think of who was attacked and who did the attacking.

Zoe Weinberg: I don’t know that it’s the best analogy, because I think different areas of technological threats have a very different profile. So looking at our competitiveness in quantum is very different than looking at disinformation operations, which is part of the reason that we think that a new directorate focused on emerging technology should have as one of its key features and ability to just constantly be scanning the horizon for different potential emerging threats, and try to stay one step ahead of it.

Tom Temin: They might be the only group then when we’re done with this to be able to take on Facebook.

Zoe Weinberg: That might be right. And another challenge that actually was raised many times among folks we spoke to is that there needs to be more connectivity on the security side between government and private sector companies so that they’re able to sort of compare notes in an open way and talk about what they’re seeing. Some of that exists, but many folks thought that that’s something where there could really be more progress and efforts can be bumped up.

Tom Temin: Zoe Weinberg is co author of a Brookings study on technology threats and a fellow at Schmidt Futures , thanks so much for joining me.

Zoe Weinberg: Thank you, Tom.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Tom Temin is host of the Federal Drive and has been providing insight on federal technology and management issues for more than 30 years.

Follow @tteminWFED

Related Stories