A rainbow over Juneteenth

Improvement may come more from individual self reflection than in some grand gesture.

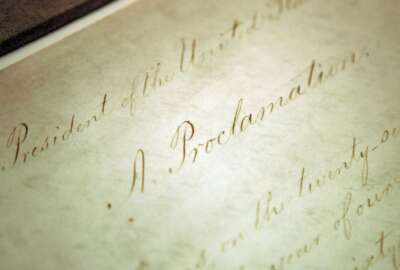

If social media existed in the 19th century, then “Juneteenth” would be September 22nd. President Lincoln finished the Emancipation Proclamation on that day in 1862. Or maybe we’d have Janteenth on New Year’s Day, the day the White House made it public in 1963.

News traveled slower back then. That’s why the celebrations occur today, the date on which the effects of the proclamation reached the most distant point of the by-then defunct Confederacy. No one had smart phones on which to receive tweets from Washington.

Like Leviticus or the Magna Carta, the Proclamation is full of legalistic language. But its importance to the advance of human dignity was, and is, unmistakable.

This morning I drive to work. I left my Harley in the garage because of the unsettled weather forecast. I was wishing I’d ridden, for right next to I-270 in lower Montgomery County appeared an enormous and vivid rainbow. Well, that’s a sign, I thought.

The other drivers seemed, as they do every morning, grimly hell-bent on getting to their destinations. I wished I’d had one of those car-roof megaphones to shout, “Slow down and look at the rainbow, people! There’s hope!”

Notwithstanding the challenges before the country at this moment, I think it’s important to remember that, since the Emancipation Proclamation, society hasn’t been static.

Take schools, for example. My parents attended D.C. public schools when they were statutorily segregated. My own high school class of approximately 650 had exactly seven black students. One lived in our town, the daughter of a federal judge. The other six were bused in daily under a Massachusetts program that still exists called METCO. One of these students showed me how to do the black national handshake. My kids went to a Montgomery County high school in which white students were the largest plurality but not a majority.

Moreover, a long series of legislative efforts, starting at the federal level and replicated at the state, have long outlawed discrimination on the basis of race and many other human factors.

Yet even as the legal background moved light years — from the Dred Scott Decision to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009 — why do issues persist? Why the variance between law and policy on one side, and practice on the other? That’s the essential question of the day.

If I had the answer, I’d tell you. But my sense is that it lies in people’s individual hearts and what they bring to the job as hiring authorities, supervisors or mentors.

The federal government operates under the perception of many minority employees that the systemic racism cited for other parts of the economy exists there also. The Senior Executives Association cites the smaller percentage of black civil servants at the SES rank relative to the overall federal workforce percentage that is black. More troubling, perhaps, than the differential is its persistence.

I spoke with Margaret Williams, the vice chair of the SEA and a federal senior manager who aspires to an SES post. As a black woman, she says she’s seen all of the good and bad. She believes change will come from a combination of ongoing analysis of hiring and promotion data — and from reinforcement of the many existing policies with respect to federal workforce diversity.

On the larger turmoil, Williams commented, “Maybe this is good for the world. It’s caused us all to take a pause.”

Look up, and you might see a rainbow.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Tom Temin is host of the Federal Drive and has been providing insight on federal technology and management issues for more than 30 years.

Follow @tteminWFED

Related Stories