Current and former counterintelligence officials say there is no known evidence so far that a victim of the Office of Personnel Management's cyber breaches has ...

It’s been nearly two years after the Office of Personnel Management first announced that hackers had stolen personally identifiable information from 21.5 million people in two separate cyber breaches, and counterintelligence officials say it’s still unclear just how the adversary may use that data, if at all.

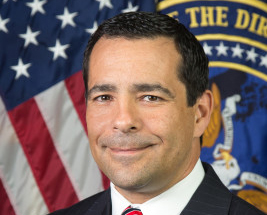

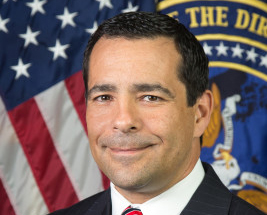

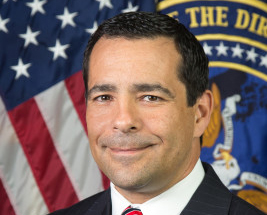

Instead, the biggest harm from the OPM breaches has been the public’s erosion of trust in the agency and in government at large to protect personal data, said Charlie Phalen, director of the National Background Investigation Bureau (NBIB).

“It’s a big deal in the sense that we need to renew the faith of the American public that we can protect that information,” he said during an Apr. 10 discussion of the long-term impacts of the OPM data breaches at the Intelligence and National Security Alliance’s Counterintelligence Threats Summit in Arlington, Virginia. “By and large, that’s the biggest piece. It is less of a big deal holistically in terms of dangers to people. The problems that will be encountered will be individuals in the wrong place at the wrong time if this is exploited in some shape or form.”

Counterintelligence officials haven’t named a specific entity responsible for the breaches but broadly link the hacks to a foreign adversary.

“There’s been no concrete evidence that anyone has, to date [and] to my knowledge at this point in time, been targeted as a direct result of this OPM [breach],” Mary Rose McCaffrey, vice president of security for Northrop Grumman and former CIA security director, said. “There’s a lot of supposition. There’s a lot of assumptions out there.”

“The reality is that we’re going to have to deal with this ambiguity for a very long time,” she added.

Bill Evanina, the director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center and the National Counterintelligence Executive, said the intelligence community and OPM are currently assessing the damage from the OPM breaches. They’re collecting information, conditioning and analyzing it to formally determine the damage, he said.

Instead, agencies should continuously educate their employees on cyber hygiene basics. Many security and counterintelligence experts, including Evanina, say the biggest threat federal employees face is the risk of falling for spearphishing attacks and clicking on links with just one or two characters out of place.

“They’re going after the weakest link,” McCaffrey said. “You can never stop educating. Tomorrow it will be something else.”

Though counterintelligence and security officials have little information about the long-term impacts of the OPM breaches, experts say impacted individuals shouldn’t be paranoid. They should take basic precautions when they post on social media, travel abroad and connect with new people online, yet those measures are no different than the steps every other American should take to protect their personal information.

“My best sense of what the long-term impacts of this is that this information in the hands of the adversary might help them learn more about me, might help them get a little bit of an edge on me, might help them sort through data, but all in all, if I take the same precautions tomorrow that I would have taken three years ago with traveling, with dealing with my business, with my life, with contacts, I don’t think I would do much very different[ly],” Phalen said.

He said he feels “fairly comfortable” that OPM’s current information system is “protected as well as it can be.”

As NBIB director, Phalen is now working with the Defense Information Systems Agency and other stakeholders to develop the specifications of a completely new security clearance information system.

Ultimately, that system should have some sort of continuous evaluation or vetting capability, something that tracks an employee as he or she moves through the workplace, Phalen said.

“We’re taking two [business process reengineering] BPR studies, one we did with OPM and NBIB… and a separate one that was done by DoD looking at the background investigation programs and matching them up and seeing some remarkable similarities,” he said. “These form the basis for how we need to think about how a process works today, how it can be improved and build something for the future that will withstand any change and direction that we take with a process. Whether it becomes continuous vetting, or we still have five-year periodic reinvestigations, some variant in between or something completely off the map, this thing needs to be able to collect, move, store and make useful the data that we’ve collected.”

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED