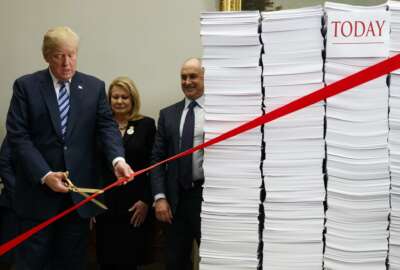

How many procurement regulations were finalized in 2017? The answer may surprise you

The Trump administration’s 2-in, 1-out regulations initiative stymied the advancement of new acquisition rules.

Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on iTunes or PodcastOne.

Here’s an interesting trivia question for all you acquisition lovers in the government: How many rules did the Federal Acquisition Regulations Council finalize during the first year of the Trump administration?

Give it some thought. Did the FAR Council make any changes from Jan. 20 to Dec. 31, 2017?

The answer is: the FAR Council issued one final rule for the entire year.

It was the decision to reverse a previous FAR rule to implement the fair pay and safe workplace executive order.

Besides that, dozens of other proposed rules were basically on hold. Now some changes occured at the agency level, but those too were few and far between.

David Berteau, the president and CEO of the Professional Services Council, said the lack of changes to the FAR and even the FAR supplements at the agency level is both good and bad.

It’s good because contracting officers and contracting officer representatives don’t need to worry about learning and applying changes.

But at the same time, it’s bad because needed changes are taking so long to happen.

A perfect example of that is the General Services Administration’s long-awaited final rule letting agency customers develop task orders under the schedules program to include other direct costs (ODCs) or order level materials (OLMs).

Industry and agencies alike have been pushing GSA to change its rules to let costs not specifically identified in the contract, such as specialized tool or test equipment, computer services or travel, but are important for the final delivery of the product or service, be allowed on schedule contracts. For example, currently under the schedules program, an agency could buy a router for their network through a time-and-materials type of contract, but if the router needed another piece of software to work appropriately, it couldn’t be included in that task order.

Roger Waldron, president of the Coalition for Government Procurement, wrote that this change is a significant step forward for the schedules.

“Customer agencies and multiple-award schedule contractors now have even greater flexibility to seek, compete, award and perform commercial-based solutions to meet agency mission requirements,” Waldron wrote in a release. “The result drives increased opportunities, competition and access to innovation from the commercial marketplace through the MAS program, reducing unnecessary contract duplication.”

Alan Thomas, the commissioner of the Federal Acquisition Service, said in a release that the final OLM rule marks another step forward in GSA’s continued efforts to modernize and transform the schedules.

“The addition of OLMs is good for government, industry and taxpayers. This much-needed important new acquisition tool provides our agency customers and industry partners with a streamlined, value-based solution that helps them meet their mission needs while saving time and money,” Thomas said. “GSA looks forward to continuing to work with our agency and industry partners through implementation to ensure a seamless transition.”

Nearly everyone is celebrating this change, but it took 17 months from proposal to completion, and it received only four comments. The final rule is basically the same as the proposed rule.

So this brings us back to the question, why, when there is near universal frustration with the federal acquisition system, are changes that would improve it taking so long?

Berteau said one obvious reason is the Trump administration’s new requirements to measure regulatory burden of a proposed rule.

“Agencies are testing out how well they can get analysis through the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs in OMB,” he said. “I don’t know how much of a delay is not having a good process to measure the burden and cost benefit analysis. The predisposition of executive order is ‘don’t issue a new regulation even if they are regulations that agencies do want to put out.’”

As agencies have to develop new analytical processes and work with OIRA on how to document the burden, Berteau said that slowed down nearly every rule. And, no one on the outside has any visibility into those processes and how long they now take.

Neomi Rao, the administrator of OIRA, said on Friday that fiscal 2017 was a “banner year for regulatory reform.” Through the implementation of the “two-for-one” executive order, OIRA says agencies saved more than $8 billion in regulatory costs, or more than $570 million per year. In addition, Rao said agencies withdrew more than 15,000 planned rules.

While it may be easy to argue against some of those 15,000 planned rules, it’s more difficult to make the case against many of the procurement rules.

If you look at the semi-annual regulatory agenda the FAR Council issued on Jan. 12, among the 16 rules in the final stage, some are badly needed to improve the acquisition process. These include set-asides under multiple award contracts, effective communication between industry and government, task and delivery order protests and clarifications of requirements to justify sole source 8(a) contracts.

Berteau said the Trump administration’s review of regulations also gave some agencies such as the Defense Department the de facto approval not to implement provisions of the 2016 and 2017 Defense authorization bills.

He said the rule to implement limited use of lowest price, technically acceptable (LPTA) is one example of how DoD seems to be slow-rolling a provision in the law it may not agree with wholeheartedly.

“I can’t tell you DoD is deliberately not implementing that rule, but the net effect is that is what they are doing,” he said.

Berteau also is concerned that the lack of final rules is creating a backlog of sorts that will impact contracting officers and program folks alike. He said this is especially concerning around the Defense FAR supplement.

“We think DoD has a plan to roll out four proposed or final or interim rules per month,” he said. “That will be difficult for industry to comment on as it will be difficult for DoD to process those comments. We are still waiting for rules from the 2017 NDAA around performance contract payments and settling undefinitized contract actions.”

Michael Fischetti, the executive director of the National Contract Management Association (NCMA), said there is good and bad to the delay in the rulemaking process.

“Contracting officers certainly would notice and so would contractors, as there is a lot of money for contract writing systems that automatically update. Over the last 12 months, nothing has changed with procurement even though people are not satisfied,” he said. “But at the same time, maybe the lack of new rules is a good opportunity for a pause to reflect on what is the right approach. Many times housekeeping does need to happen, but maybe more communication, more adoption of industry best practices and a review of socio-economic goals need to be looked at, and we need to figure out how to improve those areas.”

Fischetti added this dissatisfaction may be leading to the increased use of other transaction authorities (OTAs) by DoD and soon several civilian agencies such as the National Institutes of Health and the Federal Aviation Administration.

In short, OTAs let agencies go around the FAR and award “contracts” for prototypes or samples. Many times, the agency then can convert those “contracts” into long-term deals without any competition or oversight from auditors.

“OTAs are not a solution. There is a reason for the FAR and many people believe the FAR isn’t a problem. OTAs have been around for a long time, and now it’s the du jour solution,” he said. “Many times there are a lot of solutions looking for a problem to solve or solution that doesn’t support the problem. It’s about the quality of the workforce, people and leadership. It’s not that the government doesn’t need to be clean up on the regulations and make things more easily understandable, but the move away from the FAR is not a good thing.”

And this brings us back full circle — when there are necessary changes that aren’t made, agencies will find work-arounds and that’s not always a good thing for government and industry.

Read more of the Reporter’s Notebook.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED