Senate mulls subpoena after White House cybersecurity coordinator declines to testify

The Senate Armed Services Committee is considering a subpoena for White House cybersecurity coordinator Rob Joyce.

Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on iTunes or PodcastOne

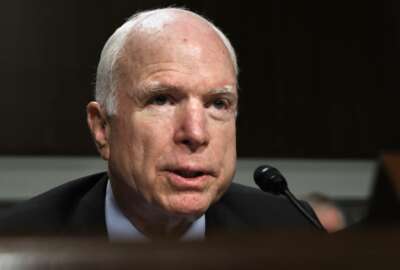

The chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee said Thursday that his panel will enter into deliberations about whether to issue a subpoena to the Trump Administration’s cybersecurity coordinator after that official, Rob Joyce, was blocked by the White House from testifying at an open hearing on federal responsibilities to defend the nation from cyber attacks.

Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz). said the administration had declined to permit Joyce to testify, citing executive privilege, since he is a member of the National Security Council and not a Senate-confirmed official.

McCain acknowledged that the White House’s position was consistent with the practice of past administrations who have sought to protect the president’s right to shield his own advisors from testimony. But he said an exception should have been made in this case, because Joyce is the only official in a position to speak to a whole-of-government approach to cyber threats, including whether the administration has a coordinated doctrine for deciding when digital attacks by nation states amount to acts of war or has a coherent strategy for responding to them.

“We have [subpoena] authorities that I don’t particularly want to use, but unless we are allowed to carry out our responsibilities to our voters who sent us here, we’re going to have to demand better cooperation and better teamwork than we’re getting now,” he said. “The committee’s going to have to get together and decide whether we’re going to sit by and watch the person in charge not appear before this committee. That’s not constitutional. We’re coequal branches of government.”

McCain and other members of the committee have pressed both the Obama and Trump administrations for years to deliver a more coordinated interagency strategy for national cyber defense. As if to emphasize the point, several members directed their questions to an empty chair prepared for Joyce at Thursday’s hearing alongside witnesses from the Defense Department, the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security.

“I personally did not see this having to be an adversarial discussion,” said Sen Mike Rounds (R-S.D). “I saw this as one in which we can begin a cooperative effort take care of the seams that we believe exist between the different agencies responsible for the protection of the cyber systems within our country.”

Rounds was among several senators who criticized the administration for delivering, as part of its written materials for the hearing, a chart of federal cyber defense roles and responsibilities for that has not been updated since 2013.

Christopher Krebs, the acting undersecretary for the Department of Homeland Security’s National Protection and Programs Directorate pointed out that federal agencies had made several changes in defining their cyber defense lanes that aren’t fully reflected in the “bubble chart,” including last year’s issuance of Presidental Policy Directive 41 and the National Cyber Incident Response Plan.

“But I share your frustration,” said Krebs, who has been in his current role for only eight weeks. “I think we have a lot of work to do, and I think this is going to require both the executive branch and the Congress working together to continue understanding exactly how we need to address the threat.”

But much of exasperation members of the Senate expressed on Thursday surrounded not just the mechanisms the government does or does not have in place to defend the nation from cyber threats, but a vacuum of information around basic definitional matters, like precisely what would constitute an attack that warrants a federal response in the first place.

More specifically, many of the questions surrounded whether alleged Russian-sponsored incursions into U.S. voting systems rise to that level.

“Tampering or a changing or interfering with state election databases, being critical infrastructure, would in fact be an attack upon our country,” said Sen. Bill Nelson (D-Fla.). “Can we stipulate that that would be the case?”

“Let the record show there was silence,” said McCain, after an awkward pause during which none of the witnesses volunteered their agreement.

Krebs said that in addition to designating election systems as critical infrastructure, DHS planned to stand up a sector coordinating council within the coming weeks to help coordinate public-and-private sector defenses of voting machines in future elections.

Latest Cybersecurity News

And last week, the department, working with 27 states and the Election Assistance Commission, established a government coordinating council to share best cyber defense practices amongst federal authorities and state election administrators after coming under criticism for failing to share adequate information about cyber attacks before a broader disclosure to state officials on Sept. 22.

“We’ve broadened the aperture, let the responsible officials know, and we gave them additional context around what may have happened,” he said.

Under the federal government’s current approach to election security, the Defense Department is willing and able help in several ways, but only in a supporting role, said Kenneth Rapuano, the assistant secretary of Defense for homeland defense. Those include assistance to governors via each state and territory’s National Guard and playing a supporting role to DHS, but only when requested.

“The focus is our protection teams out of the Cyber Mission Force, and those are skilled practitioners who understand the forensics issues, the identification of the challenges of types of malware and different approaches to removing the malware from the systems,” he said. “It takes a direct request for assistance from DHS to the department, and we have authorities all the way down to COCOM commanders, specifically Cyber Command [to provide that assistance].”

But senators were clearly frustrated by what they view as an insufficiently muscular federal effort to defend election systems and the other 16 categories of critical infrastructure DHS has defined thus far.

Although in each case they are highly decentralized systems, their operators cannot be expected to protect themselves without significant federal help, especially when their cyber adversaries are centralized and capable nation states, said Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass).

“I don’t think anybody in this room thinks that the commonwealth of Massachusetts or the city of Omaha, Nebraska, should be left by themselves to defend against a sophisticated cyber adversary like Russia,” she said. “If the Russians were poisoning water or setting off bombs in any state or town in America, we would put our full national power into protecting ourselves and fighting back. The Russians have attacked our democracy. I think we need to step up our response, and I think we need to do it fast.”

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jared Serbu is deputy editor of Federal News Network and reports on the Defense Department’s contracting, legislative, workforce and IT issues.

Follow @jserbuWFED

Related Stories