7 steps to raise the bar on your agency’s enterprise risk management strategy

A new playbook from the Chief Financial Officers Council and Performance Improvement Council aims to help agencies stand up enterprise risk management programs, as...

Agencies have a new “playbook” to help them embrace and manage a broader, top-down view of risk within their organizations.

The playbook, which the Chief Financial Officers and Performance Improvement Councils released July 29, outlines a framework that agencies can take to stand-up an enterprise risk management (ERM) program.

The mandate came in the form of the Office of Management and Budget’s long-awaited update to Circular A-123.

In the past, agencies took a “check-the-box” approach to managing their financial and internal controls. But ERM forces organizations to think more broadly about risk and how it could hinder — or help — an agency’s ability to meet its mission.

Todd Grams, a managing director at Deloitte, said OMB is trying to help agencies use those internal controls as a way to mitigate and make decisions around risk.

“Government programs are becoming more complex, while resources are becoming harder to come by,” he said. “What ERM can do for agencies is help them better manage their risks, which will reduce the chance of a crisis occurring, allowing leadership to focus more on their mission, their strategy [and] their objectives.”

For most agencies, ERM is still at a relatively immature stage, though some agencies have stood up programs on their own. Grams said agencies are beginning to take initiative and move in the right direction.

“We’d just like to see velocity of that direction pick up,” he said. “I think A-123 is going to help to do that.”

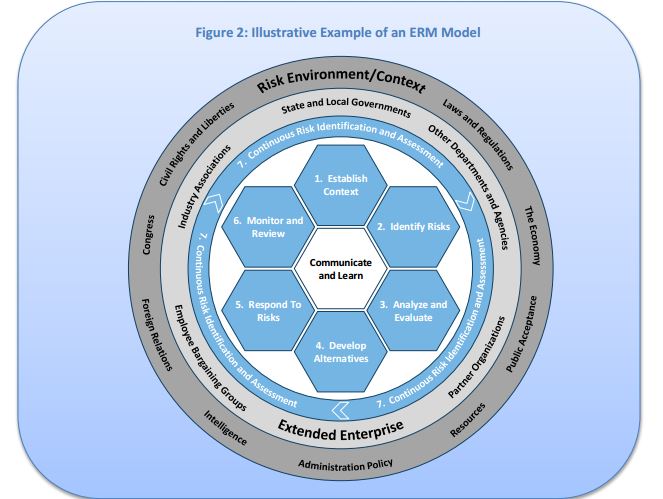

It’s ultimately up to each agency to decide how it will implement ERM, but the playbook suggested a seven-step model.

1. Establish context: think about the agency’s mission and operations, the people and stakeholders who rely on them and how failure may impact them.

2. Identify risks: Managers and subject matter experts should take the lead on finding and keeping a list of potential risks.

3. Analyze and evaluate: Review the root causes, sources and probability that the risk may happen. Consider inherent risk that may already exist within the agency.

“Taking intelligent risks at the right time can actually help an agency better achieve their mission goals and objectives,” Grams said.

4. Develop alternatives: Come up with response options to “accept, transfer, share, avoid or mitigate major risks.” Weigh the pros, cons and cost implications for each option.

5. Respond to risks: Decide how to allocate budget resources to respond. Keep track of the major milestones and ensure that the agency is following the response plan.

Each agency will likely have its own preference for an ERM leader depending on the size of the organization and its mission, Grams said.

“You really do need a point-person who owns the ERM program,” he said. “They don’t own the risks. The risks have to stay with the programs in which they are.”

6. Monitor and review: Keep track and update agency progress in addressing risk.

“This review should occur semi-annually at a minimum,” the playbook said. “As part of this ongoing process, risk personnel should work with senior leadership to determine if originally identified risks still exist, identify any new or emerging risks, determine if likelihood or impact has changed and ascertain the effectiveness of controls or mitigants put in place.”

Agencies are expected to develop some sort of risk “register” or dashboard to communicate the status of their risk activities, the playbook said.

7. Continuous risk identification and assessment: The whole process should happen in iterative stages throughout the year, not all at once.

And agencies should integrate risk planning into the other, existing procedures they have on performance and budget management.

Culture, leadership

The playbook acknowledged that implementing an enterprise risk management strategy will be a significant culture change for some agencies.

That culture change is perhaps the most difficult part of implementing ERM, Grams said. But it’s also the most important.

“When you start the ERM program out…make sure that people understand it’s there to help,” he said. “If you share your risks, if you’re transparent about your risks, then there’s a chance that more people, resources, IT dollars, whatever, can be brought to bear to help address that risk, and that you’re not out there on your own. It’s not a ‘gotcha’ exercise. It’s not an oversight exercise trying to figure out what you’ve done wrong.”

Grams said the goal is for employees to feel encouraged and recognized for bringing up risks to an agency’s leaders.

Communication between agency risk leaders and their stakeholders is also key.

A-123 does not require that agencies hire a specific chief risk officer to manage ERM, but it does make it clear that they should have one senior official held accountable to the program, along with an appropriately sized team to help stand up ERM.

“If an agency does not have a CRO or intend to hire one, it should also carefully consider where the core team fits in the agency to make it most effective,” the playbook said. “While agencies should be careful about building an ERM empire, the size of the ERM team should reflect the needs of the organization to support effective risk management.”

The playbook also suggests that large cabinet agencies have their deputy secretaries take on the responsibility as a “risk management chair,” to lead monthly meetings on the department’s ERM activities.

The personality of the risk leader is crucial as well, Grams said.

Standing up a new program in government is difficult, and agencies will need to choose a leader who can own and influence ERM implementation.

“It’s also good if that person in the organization that they’re running has strong relationships already established in the agency and that they’re well-respected,” Grams said.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED

Related Stories

With A-123 update, OMB knits together risk management, internal controls