New data in the Government Accountability Act’s fiscal 2020 report to Congress on bid protests shows that vendors received some sort of corrective action 51% ...

If you got the odds the Government Accountability Office is giving vendors on bid protests in Las Vegas, you’d be rich and famous, and probably under investigation by the FBI for insider trading.

Imagine winning 51% of your bets on sports games or horse races? Those are the odds GAO is giving contractors who submit a protest to their office.

New data in GAO’s fiscal 2020 report to Congress on bid protests shows that vendors received some sort of corrective action 51% of the time.

“The reasons agencies take corrective action are diverse, but certainly they are over worked and understaffed so they have less time to follow protests through. I think they see corrective action as way to dispense with a protest and give contractors some relief,” said Eric Crusius, a procurement lawyer and partner with Holland and Knight. “With all the money flowing through the government because of the pandemic, protestors are able to find reasons to protest more frequently. As money leaves doors more quickly, there are more opportunities to find mistakes made by agencies. We’ve seen a lot more corrective action over the last year to the point where I’m almost surprised when it doesn’t happen.”

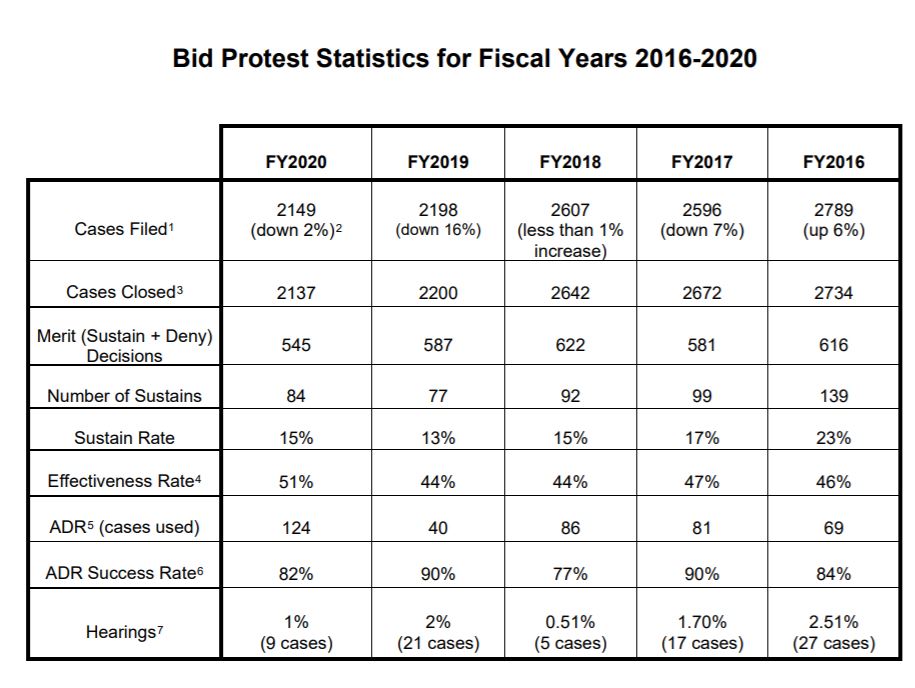

GAO says the effectiveness rate, which measures how often an agency takes corrective action or the protest is sustained, jumped to 51% from 44% in 2019 and 2018, respectively. The agency says the sustain rate is 15%, which is up from 13% the year before too.

Shane McCall, the managing partner of Koprince Law, said he sees agencies making decisions about taking corrective action fairly quickly after the contractors file the complaint, especially if GAO rejects the government’s dismissal request.

“Sometimes you worry they will take corrective action to blunt the attack of the bid protest but it may not address the root problem,” McCall said. “Sometimes you’d wish it would go to decision versus having to file the same protest even after corrective action.”

Just looking at some of the high-profile acquisitions in 2020—the Defense Department’s DEOS and JEDI and the General Services Administration’s 2GIT, to name a few—the agencies didn’t take the protests to decision and decided to correct flaws in their evaluations or solicitations. Now not all corrective action means vendors get the changes they sought and many can point to agency corrective actions that never breached the surface of the problem.

Crusius said this may be because agencies are taking a path that is less risky so as not to have to pay attorney’s fees if a protest goes to a hearing or even alternative dispute resolution (ADR).

GAO said ADR was another growth area in 2020. The number of cases using ADR jumped to 124 last year from 40 in 2019 and 86 in 2018, respectively.

Rob Burton, a former deputy administrator in the Office of Federal Procurement Policy and now a partner with Crowell and Moring, said GAO has been pushing ADR aggressively and encouraging examiners to engage in more of it.

“What’s not good about ADR is you don’t get a written opinion for precedent. A lot of clients would prefer to have more formal resolution of matter,” he said. “But ADR generally is pretty good with an 82% success rate, which means both parties resolve cases to their satisfaction.”

Basically, the odds that a protest will be successful in some way are greater than at any time in the last five years.

Barbara Kinosky, the managing partner of Centre Law and Consulting, also pointed out that GAO said in the report to Congress that all agencies followed their recommendations. This is the first time this has happened in years as well.

“I do think we will see the effectiveness rate continue to increase,” Kinosky said. “Part of the reason is we are all working from home and the extra hours in the day give people the opportunity to look at records in more detail and they were more able to pick up things like ambiguities or potential problems in procurements.”

At the same time, however, the number of protests dropped for the second year in a row. Burton and other experts say there are several reasons for the decrease.

“Part of the reasons for the number of protests dropping is DoD’s task order threshold went to $25 million from $10 million in 2019. I think this did have an impact because it was a big jump for DoD and more and more work is going through task orders,” Burton said. “Agencies also are doing more enhanced briefings as required by the 2018 defense authorization act. That obviously can’t hurt, and as more agencies do good debriefings, the number of protests will go down.”

Paul Debolt, the chairman of the government contracts group at the Venable law firm, said enhanced debriefings help vendors understand agency decisions and addresses long-standing problems of not doing a good job articulating the award rationale.

“A lot of the questions are focused on concerns they have about the initial information about why the agency made the decision they did,” he said. “As long as the agency is thorough and relatively transparent in award decision there are a lot of companies who decide not to protest. The other thing that factors in to a protest is whether the disappointed offeror is the incumbent. Based on my experience, if a company is the incumbent and the contract is significant enough, they will look pretty hard at filing a protest. But if an incumbent didn’t get the award and the agency can articulate their reasonable basis, many will walk away and not throw good money after bad.”

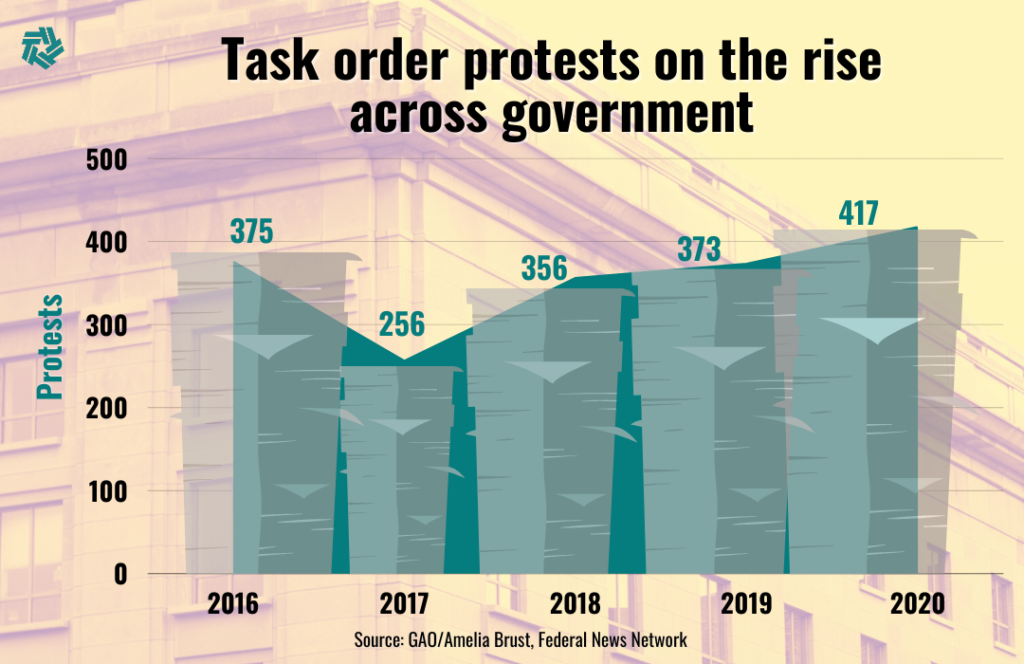

The other data point to note is the 15% increase in the number of task and deliver order protests to GAO last year.

Legal experts couldn’t point to a specific reason for the increase, other than agencies are spending more money through multiple award and governmentwide acquisition contracts than ever before.

Crusius said the reason these types of protests haven’t increased even more dramatically may be because vendors have an ongoing relationship with agencies under these types of contracts and they don’t want to sour it.

Finally, one last data point from Crowell and Moring’s Burton.

He pointed out that GAO held hearings for just 1%, or just nine cases, out of more than 2,149 cases filed in 2020. That is way down from 2011 (8%) and 2009 (12%) when many more cases received hearings.

“I think this shows the bid protest process is pretty much a paper process, a review of paper records. I’m not sure if GAO just doesn’t feel like they need oral testimony and can just make a decision based on the administrative record,” Burton said. “It’s only in complex cases and usually something that has to do with cost and price that GAO thinks hearings would be beneficial. I think there are plenty of cases where live testimony has a role to play. The analogy I would use is in the civil or criminal court system. They seem to understand the value of having testimony and witnesses. I’m not sure why GAO is different in that regard.”

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED