Bigger is not better for OPM

The Office of Personnel Management's data breach has people questioning the competence of OPM’s staff and leaders, and asking why OPM exists in the first plac...

This column was originally published on Jeff Neal’s blog, ChiefHRO.com, and was republished here with permission from the author.

The Office of Personnel Management is getting the kind of attention that most federal agencies never want. The data breach has people questioning the competence of OPM’s staff and leaders, and asking why OPM exists in the first place.

So many people have been affected, and in such a personal and lasting way, that business-as-usual is simply not a viable option. So what does something other than business-as-usual look like?

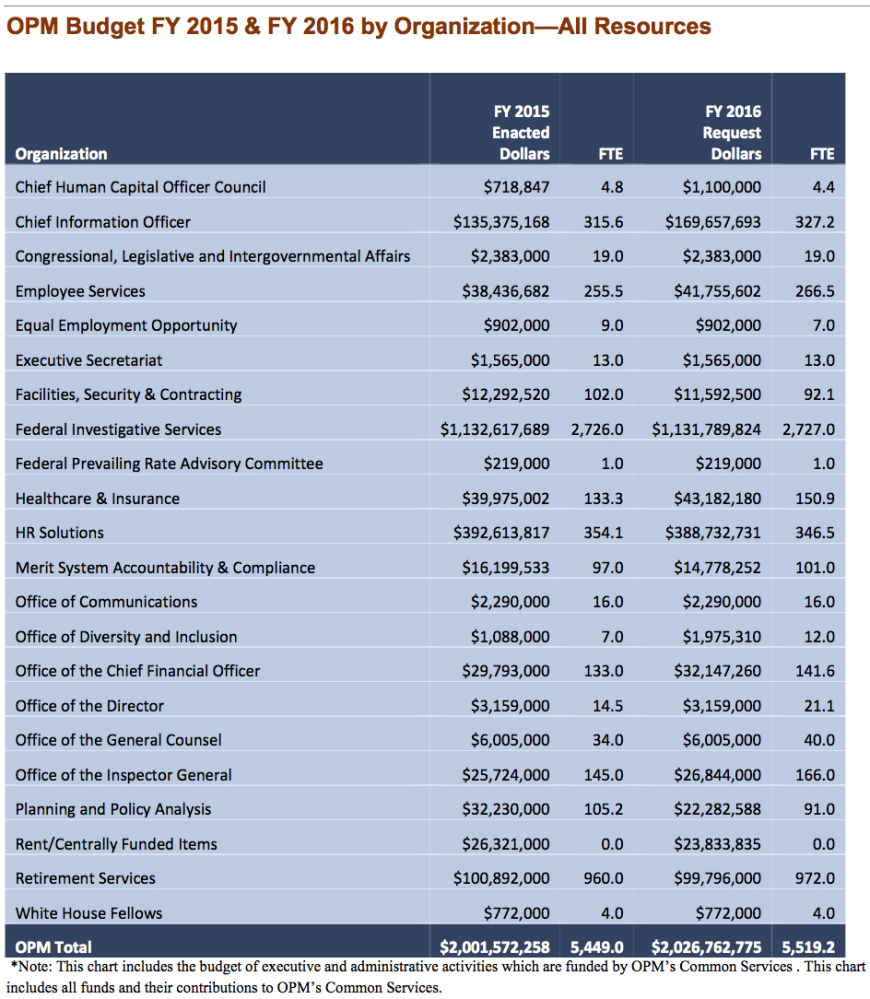

OPM says its mission is “…to recruit, retain and honor a world-class workforce for the American people.” Although OPM is small when judged by the standards of Defense, Homeland Security, VA and other Departments, but with 5,500 employees and a budget of $2 billion, it is considered to be a “large” federal agency.

A deep dive into those numbers offers some surprising insights. When combined with a look at OPM’s history and how it operates, I believe it shows a clear path forward for OPM that can return the agency to credibility and effectiveness in its core mission.

The Numbers

That $2 billion in OPM’s 2015 budget contains a surprisingly small amount of appropriated money. More than $1.6 billion is from the OPM revolving fund and $118 million comes from Trust Fund accounts.

The revolving fund includes revenue and expenses related to background investigations, USAStaffing, USAJobs, consulting services, and other services for which OPM charges a fee to agencies.

The majority of revenue and expenses in the revolving fund are associated with background investigations. Trust dollars come from the Civil Service Retirement and Disability, Federal Employees Health Benefits, and Federal Employees Group Life Insurance Funds.

Most surprising is the number of dollars and employees associated with background investigations. More than half of OPM’s money ($1.13 billion) and employees (2,726) are involved in background investigations.

The Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 provided that “the function of filling positions and other personnel functions in the competitive service and in the executive branch should be delegated in appropriate cases to the agencies to expedite processing appointments and other personnel actions, with the control and oversight of this delegation being maintained by the Office of Personnel Management to protect against prohibited personnel practices and the use of unsound management practices by the agencies.”

The core mission of OPM is crafting regulations and policies to implement the merit system and to oversee agencies’ hiring practices. In addition, OPM administers federal pay, retirement and health and life insurance systems.

Those roles are so critical that I believe it is essential to have an independent agency to carry them out. That does not apply to many of OPM’s other roles. In fact, OPM is offering so many services now that they make up the majority of the agency’s budget and staff and it is difficult to see how it can excel in all of them and still devote sufficient executive time and attention to its core mission.

Part of the problem is that OPM has gotten trapped in a fee-based arrangement where they have to sell services be able to support the core mission. Congress could help by adequately funding a smaller and more focused OPM through appropriations, rather than asking them to rely so heavily on fees.

Just Say No

When he returned to an Apple, Inc. that was on the verge of bankruptcy, Steve Jobs famously said “We had to decide what are the fundamental directions we are going in and what make sense and what doesn’t. Focusing is about saying no.” He went on to explain that saying no makes a lot of people unhappy, but the results of focusing are worth the pain.

It is time for OPM to start focusing by saying no to the roles that are not part of their core mission. Here are a few good places to start:

Say no to background investigations. The idea of having OPM conduct background investigations seemed sound. They are related to hiring and consolidating the work would probably be more efficient. Sounds great, but now more than half of OPM is handling background investigations. And we see that having background investigation data for 90% of the government in one place creates a huge target for hackers. The outcome is likely to cost far more than we ever saved by consolidation. OPM’s should get out of background investigations entirely and the work should either be decentralized into the large Departments and Agencies or, because of the intelligence value of the collected data, assigned to an agency more focused on intelligence or law enforcement.

Say no to selling software, unless it is necessary to further the core mission. Shared services are a sound idea but not when commercial off-the-shelf products are available. OPM is currently the largest provider of talent acquisition software for the federal government. USAStaffing is used by agencies representing more than 70 percent of the federal work force. The fact that there are good, fully federalized, commercial products available from companies like Monster, Acendre and Economic Systems has not stopped OPM from investing time and money in developing software and competing for market share. There is no compelling reason for the government to remain in this market. The exception is OPM’s USAJobs system. Although there are excellent job board systems available commercially, the need for all of the talent acquisition systems to work seamlessly with the government’s job board makes a government-owned system make sense. Otherwise we could find ourselves in a position where the company that provides the job board could make their software work better with it, thereby forcing the other companies out of the federal market. USAJobs is a great example of the need for appropriated money. OPM currently has to charge every agency a fee for the system. It would be far more efficient to simply put the money there to begin with rather than going through the gyrations of putting it in other Departments and agencies and then making them write a check.

Say no to selling services when it creates an organizational conflict of interest. In addition to background investigations, OPM sells consulting services in a variety of areas. It does some of that through the private sector and some using OPM staff. Most of the work that is done using the private sector (through firms like my employer and others) is through OPM’s Talent and Management Assistance contracts. Federal agencies have used them successfully for years and they have been one of the goto sources for federal agencies. The replacements for the TMA contracts are moving to GSA as part of a new partnership between OPM and GSA. That is an excellent move by both agencies – it puts a contracting agency in charge of the contracts. Where there is an organizational conflict is in areas where OPM is responsible for regulations, policy, and oversight, but sells related services using its own employees to do the work. Although OPM attempts to separate their policy and oversight work from their fee-for-service activities, it is hard not to be influenced by the need for continued revenue. For example, when I was DHS Chief Human Capital Officer, during one CHCO Council meeting a former OPM executive expressed concerns that what the CHCOs wanted for a new policy would affect OPM’s business for one of its fee-based services. Former Director John Berry made it clear that he would not make policy based on potential loss of fees, but the fact that the issue was raised shows that the concern is legitimate. Work that presents a potential conflict should be moved, along with the associated staff, to another agency that provides shared services. OPM should provide fee-based services only where it makes sense to do so, such as administering the White House Fellows program. I have to admit I’m on the fence on services related to advertising jobs for agencies. While I could make the argument that OPM writes regulations and conducts oversight for staffing functions, employment services have been part of the mission since the beginning of the Civil Service Commission. The difference is that now agencies have to bring their checkbook to get the services.

Say Yes to a Revitalized OPM

If OPM sheds the roles that are not necessary to carry out its core mission, it can begin to offer some real benefits that would help it “recruit, retain and honor a world-class workforce for the American people.” Among the things OPM is ideally suited for and should say Yes to are:

Say yes to analytics. Everyone learned that OPM has massive amounts of data on the federal workforce. They also have data on hiring, separations, retirement, and virtually every aspect of the federal workforce. While OPM uses some of that data to inform its policy development, workforce analytics should be a key offering. For example, by linking data from the hiring process with performance results, OPM data could help agencies identify the hiring methods that produce the highest performing employees. The opportunities to turn that data into usable information are tremendous. OPM could provide detailed data sets to agencies that they could use to conduct meaningful analytics.

Say yes to classification reform. OPM could dramatically simplify job classification by reducing the number of job series and simplifying classification standards. Doing so would also make OPM’s job of keeping the remaining standards up to date far easier. There is no need for legislation to do that. OPM has the authority to start doing it today.

More Commentary from Jeff Neal

Say yes to more hiring reform. The initial movement toward hiring reform begun by President Obama was a great first step, but much of it was focused on telling agencies they had to do better in running the hiring process. However, much of what makes the federal hiring process so cumbersome is driven by regulations rather than law. OPM should identify everything that it can do to make its own regulations more effective.

Say yes to a new approach to performance management. Very little of what drives people crazy about federal performance management is driven by the law. OPM has tremendous authority to craft and implement new regulations that would simplify and dramatically improve performance management.

Say yes to customer service. OPM should also consider a reorganization of the remaining work to focus on key mission areas and to develop a more strategic approach to integrated policy development and oversight. Its current structure does not appear to produce well-coordinated policy guidance that takes the entire employee life cycle into account. Doing so would help revitalize their advisory services work so agency HR staff have easy access to the people who write regulations and policies. In the past, OPM was a superb source of insight. There are still a lot of talented and knowledgeable HR experts at OPM, but their current structure makes it more difficult for agencies to find the right person to ask for help.

Some of the people I have talked with regarding OPM say the agency should never agree to shrink from 5,500 employees to 2,500. They say that makes OPM a more likely target to be consolidated into another agency, such as GSA or even into the Office of Management and Budget. That may be true, but if we believe people are such an important resource, and talent management is such a critical issue, having an effective, independent agency to manage people programs is too critical to make it a tacked-on feature of some other agency. A newly focused and high-performing OPM could help the federal government move beyond its current outdated approach to talent management without having to ask Congress to change the laws regarding hiring, classification and pay. I believe OPM still has the potential to be the talent management agency the government needs. The benefits to the people and to the government are too great to avoid acting solely because of internal government politics.

Jeff Neal is a senior vice president for ICF International and founder of the blog, ChiefHRO.com. Before coming to ICF, Neal was the chief human capital officer at the Department of Homeland Security and the chief human resources officer at the Defense Logistics Agency.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.