Exclusive

Hundreds of federal employees teleworking overseas set to receive pay bump under NDAA

A provision in the 2023 NDAA will establish a locality pay equivalent for hundreds of civilian federal employees working under the Domestic Employees Teleworkin...

Hundreds of federal employees are about to see their paychecks go up, and it’s not just because of the 2023 pay raise.

The Civil Service Federal Employee Serving Overseas Pay Equity Act will establish a locality pay equivalent for some 265 active civilian federal employees, mostly State Department employees, working under the Domestic Employees Teleworking Overseas (DETO) program.

The DETO program is offered to spouses of military and Foreign Service officers to continue their federal careers after being stationed overseas. But employees in the program, colloquially called DETOs, didn’t receive locality pay, or any type of equivalent, prior to the new legislation, which was included in the 2023 National Defense Authorization Act.

Locality pay gives most federal employees on the General Schedule an extra boost to their paychecks, based on where they work and live. The 54 current locality pay areas, however, only cover feds working within the geographic United States. The law previously said DETOs could not be given locality pay, regardless of the local living conditions abroad.

With Congress addressing the locality pay issue for DETOs, the State Department is able to further tap into telework as a tool to improve the morale of Foreign Service officers and their family members looking to join the federal civil service.

Michael Phillips, deputy assistant secretary of the State Department’s Bureau of Global Talent Management, told Federal News Network in a statement that civil service DETO pay “has been a long-term pain point in the DETO program,” and applauded Congress for ensuring pay parity between civil service and Foreign Service DETOs.

“This is an important step in promoting equity, opportunity and flexibility for our workforce. We will continue our efforts to support and grow the DETO program, as a key component of our efforts to recruit and retain a diverse and talented workforce and to help keep families strong and united,” Phillips said.

The NDAA now requires civil service members under a DETO agreement to be paid the lower of two options: either what they would have been paid in the U.S., or what a member of the Foreign Service at an equivalent level is paid.

Rep. Joaquin Castro (D-Texas) originally introduced the standalone bill, and Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.) led the effort on companion legislation. Ultimately, the bill garnered broad bipartisan support.

“Every year, we lose too many of our best and brightest public servants because of the financial strains of overseas assignments,” Castro said in a press statement. “With the passage of the Civil Service Federal Employee Serving Overseas Pay Equity Act, military and foreign service spouses will no longer be financially penalized for serving their country from abroad.”

The federal government now has 60 days to implement the changes from the bill, meaning DETOs will likely see the effects of it in their paychecks sometime in March.

“Our nation’s armed forces and overseas public servants, as well their families, make sacrifices day-in and day-out for our country,” Van Hollen told Federal News Network in an email statement. “We should be doing all we can to support them when they’re abroad — and that includes ensuring fairness in spousal pay. This common-sense fix will help do just that.”

A yearlong push for pay equity

Both DETOs and federal advocacy groups saw the passage of the legislation as a victory. It’s a change many advocates have pushed for, for at least the last year.

One of those advocates is Wendy Rejan, a State Department Foreign Service officer and military spouse. She helps lead the State/USAID Military and DoD Family Employee Organization.

“We were thrilled to see pay equity for civil service DETOs signed into law by the president recently,” Rejan told Federal News Network. “We appreciate the bipartisan support from Congress on this issue. It will have a huge positive impact on military and DoD families and help our community maintain dual federal-military careers and keep families together.”

American Foreign Service Association (AFSA) President Eric Rubin said two State Department employee organizations — Working in Tandem and Balancing Act — along with the spouses of Foreign Service officers led an “intensive push” in 2022 to address the locality pay disparity for DETOs.

Working in Tandem focuses on supporting two-career couples in the Foreign Service, while Balancing Act leads on work-life balance issues in both the Foreign Service and civil service.

“If you have a civil service spouse and you’re in the Foreign Service, and your spouse goes overseas with you, they’re lucky if they were able to arrange to telework from overseas to their U.S. domestic job,” Rubin said.

Foreign Service spouses face many of the same employment challenges as military families. The biggest challenge common to both is the requirement to move to a new post every few years. Foreign Service officers change posts about every two-to-three years.

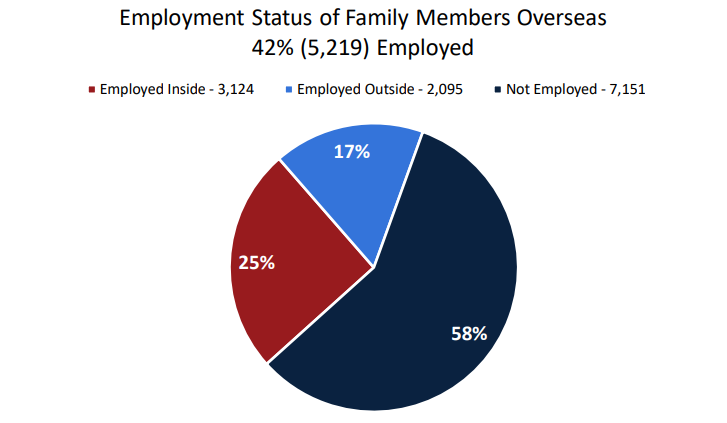

Frequent moves and the challenge of finding work in a new country make it hard for Foreign Service families to stay employed. State Department data from fall 2022 shows that about 58% of the 12,370 Foreign Service family members living overseas are unemployed.

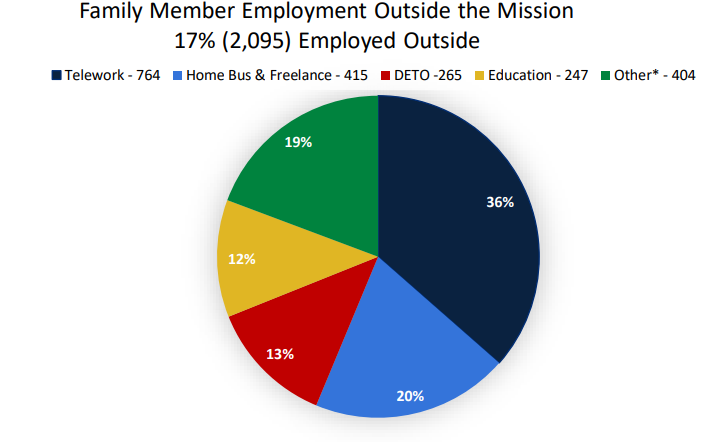

About 25% of Foreign Service family members are employed “inside the mission,” in jobs at their post overseas. Nearly 2,100 individuals — about 17% of all Foreign Service family members — hold jobs outside of the U.S. diplomatic mission. Within that 17%, the data shows about 764 individuals rely on telework to hold a job, 265 of which are DETOs.

Celine Erickson, president of the Associates of the American Foreign Service Worldwide (AAFSW) said the State Department’s data shows a “significant share” of adult family members are DETOs.

“It is growing across the broad spectrum of all embassies globally,” Erickson said. “This year’s NDAA has serious potential to really improve the lives of many federal employees, especially for our community at-post overseas.”

Erickson said AAFSW supports the locality pay adjustment for DETOs in the NDAA.

“It’s all about ensuring that diplomatic spouses and dependents are not penalized for serving the United States alongside their family members in the Foreign Service,” Erickson said.

AFSA Director of Advocacy Kim Greenplate said annual State Department authorizations in the NDAA give Congress an opportunity to quickly introduce reforms and changes to the department’s workforce.

Congress included State Department authorization in the fiscal 2022 and 2023 NDAAs, but had excluded this re-authorization language for a nearly 20-year streak prior to that.

“This only took a year, which is certainly one of the faster timelines I’ve seen for something that does cost the U.S. government taxpayer dollars,” Greenplate said. “It does make the case for when there’s a problem, and it needs addressing, and Congress sees the merits of it and wants to act, it can get done, and it can get done quickly. But there always needs to be a legislative vehicle for us to move it.”

Telework opens the door to career stability

DETOs, and teleworking overseas in general, didn’t originate with the COVID-19 pandemic. The DETO program dates back to 2009, and is intended to provide more secure career options for spouses of military or Foreign Service members who were stationed overseas.

Although the majority of DETOs work at the State Department, any federal agency can set up its own DETO program. There are DETOs, for example, working at the Federal Aviation Administration and the Commerce Department.

The rise of telework and remote work opportunities at agencies since the start of the pandemic has led to a significant expansion of the DETO program. The number of DETOs has almost tripled in the last two years, increasing by about 165%, from about 100 to 265 total employees.

“Teleworking is now not just common, but it’s part of the whole normal package,” Rubin said. “It’s not easy to be a federal employee these days, but this is the kind of concrete help that I think will make a real difference.”

The State Department, prior to the pandemic, reached an interim agreement with the Defense Department, letting DETOs married to military spouses work from military housing overseas.

Before the creation of the DETO program, though, spouses of Foreign Service officers and military members who were stationed overseas often had to quit their federal jobs when they moved.

“Maybe if they were lucky, they could find something in an embassy or in the local market. But those positions tend to be lower paid, and without that continuity that someone would hope for in a career,” Michelle Neyland, a State Department employee in the DETO program and advocate of the legislative change, told Federal News Network. “[With the DETO program,] it became more possible for these spouses to instead get hired as civil service officers throughout the U.S. government using their professional skills … That created more stability in their careers.”

The DETO program lets employees continue on their career track, regardless of where their family is posted. Agencies also get to hold onto their employees. But at the same time, without locality pay, many DETOs, often Eligible Family Members (EFMs) at the State Department, were left feeling unsatisfied in their positions.

“[As EFMs,] we are supporting our Foreign Service or our military spouses, supporting the mission of our country, packing up our whole house, and the stress that comes along with that,” Neyland said. “Then as soon as we got to post, we opened up our paycheck and it had just dropped. It was not a good feeling; it was very demoralizing. Sometimes [employees in the] civil service DETO program who are supervisors actually earned less money than the people they supervised.”

But now with the new legislation, many hope that it will lead to better employee satisfaction, as well as improvements in federal recruitment and retention overseas.

“Hundreds of Foreign Service and military families will benefit from this immediately, and tens of thousands of spouses stand to benefit in the future,” Neyland said.

‘You can’t afford to work’ with pay disparity

Prior to the legislation, DETOs’ pay would drop once employees moved abroad and continued working in their current positions. It’s the only federal employee cohort facing this specific type of pay disparity.

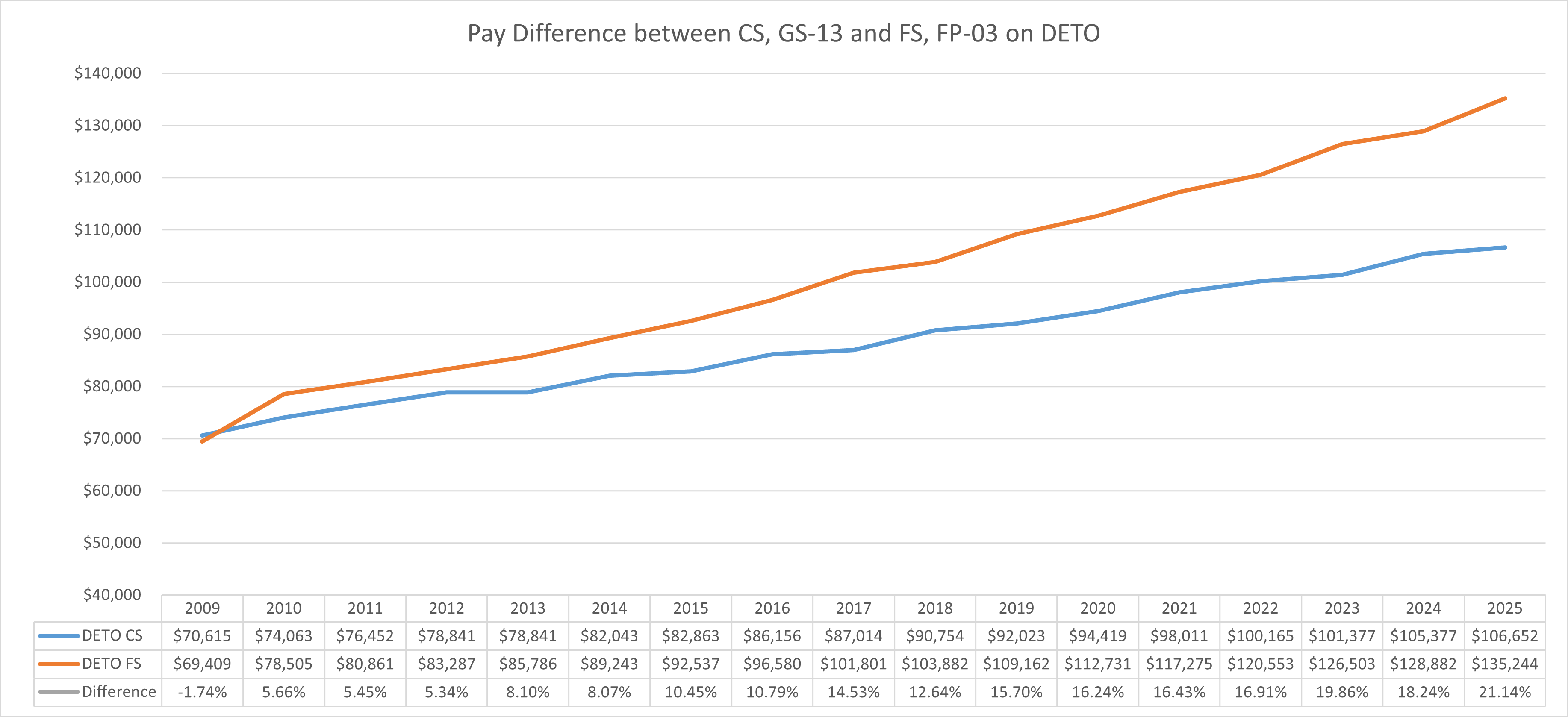

The pay disparity between federal employees working in the same position in the U.S., versus overseas, can be significant.

“We’re potentially looking at 30% in some cases,” Rubin said.

About 90% of current State employees in the DETO program are from the Washington, D.C. area. That means when they move abroad, they lose that D.C. area locality pay boost, which is currently 32.49%.

For example, the pay gap for a GS-13, step 1, employee with Washington, D.C. locality pay, versus a DETO in the same grade and step, but not receiving locality pay, has about a $25,000 difference in base salary.

In another example, under the current DETO program, an entry-level human resources assistant making $36,488 in San Antonio, Texas, would see their salary fall to $31,083 if they followed their spouse on an overseas assignment, according to a press release from Castro.

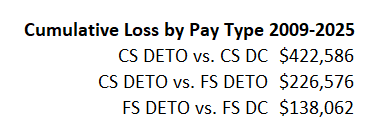

The exact disparity in pay depends on the compared groups of employees. For example, prior to the locality pay equivalent, DETOs in the civil service would make about $422,000 less than their counterparts working in D.C., when cumulatively adding the lack of locality pay each year from 2009 to 2025.

The disparity can have exponential differences over time, too. The lack of locality pay could, for instance, cause a larger impact on retirement savings over the course of one’s career.

Foreign Service officers receive a 25% pay bonus for working in high-risk, high-threat posts, but DETOs don’t receive any additional pay, “even though they were facing the same danger as their spouses,” Rubin said.

“It was really not just an equity issue, but it was discouraging people from working for our country overseas,” he added.

In contrast to the previous lack of locality pay DETO program, Foreign Service officers do receive a locality pay equivalent, through Overseas Comparability Pay (OCP). It’s intended to bring Foreign Service officers up to equivalent pay for the Washington, D.C., locality pay area.

But OCP has been implemented gradually, and so far, only includes two-thirds of the full pay adjustment. The locality pay adjustment for those employees is currently set at 21.2% of base pay, or two-thirds of Washington, D.C. locality pay.

Without locality pay for the DETO program, many of the employees considered leaving for other jobs, or leaving the workforce altogether.

“If these employees are able to find other positions that are going to be more accommodating of them, in terms of working overseas in some type of teleworking environment, then these agencies could very well lose these employees,” a Castro staff member said in an interview with Federal News Network.

Rubin added that the locality pay issue hit especially hard for Foreign Service families stationed in major cities with a high cost of living, such as Geneva or Tokyo.

“If you have little kids and you’re teleworking, you probably need child care, and the cost of health care in a place like Geneva is a lot more than in D.C. where it’s already pretty high. And you may just make the calculation that you can’t afford to work, and then we lose somebody who’s already had experience and training and all of that,” he said.

Gender equity, morale, retention and more

The lack of locality pay or an equivalent was also a gender-related issue, since the majority of DETOs are women. Historically, in heterosexual marriages, it has usually been men who take military or Foreign Service postings abroad, and their spouse would go with them, though that has somewhat changed over time.

It’s estimated that about 67% of current civil service employees in the DETO program at the State Department are women. The program lets these women, who may have otherwise had to end their careers, continue teleworking in the same job abroad.

“[The lack of locality pay] undermines the financial security of your family and it undermines your long-term security, because [it impacts] retirement contributions,” a Castro staff member said. “[The DETO program] is one of the few avenues for military spouses to have this stable job.”

The difficulty of becoming a DETO for Foreign Service spouses led to them finding other opportunities for work. It’s a contributing factor to a decline in Foreign Service morale.

AFSA, in a 2021 retention survey, found that Foreign Service members who left prior to reaching retirement age ranked “family issues” as their top reason for leaving.

Rubin said conversations with Foreign Service spouses and State Department employee groups revealed that a lack of employment opportunities for Foreign Service families stood out as a significant component of these family issues.

“This is just one of so many things that have made it hard for people to join and stay in the Foreign Service and serve our country overseas,” he said.

Greenplate said AFSA brought the issue to Congress — particularly Castro and Van Hollen — and sought a legislative fix as part of the State Department authorization contained in the NDAA.

“We took that to heart. This is where our members want us focused, on opportunities for family employment and family issues,” Greenplate said.

Erickson said an easier pathway to becoming a DETO reduces the instances where Foreign Service families are separated because of work, and will allow the State Department and other federal agencies to tap into a broader pool of talent.

“The better the family feels, the better the work is going to be done. That’s why it’s important to support these kinds of initiatives,” she said. “With this new legislation, I think there will be [fewer] missed opportunities, because there are going to be more adult working family members now.”

And the issue is not only about employee morale, but also recruitment and retention at federal agencies.

“If somebody is thinking of joining the Foreign Service, and has a spouse in the civil service, being able to say, ‘if your office agrees, and you go overseas, you’ll get paid the same differentials, locality pay that I get overseas, wherever we go,’ that may make that couple decide that the Foreign Service is feasible,” Rubin said.

Federal employee morale in general has gone down significantly over the past decade. The State Department peaked in 2010 with a 70.8% engagement and satisfaction score in the Partnership for Public Service’s annual Best Places to Work in the Federal Government rankings.

The department in 2021, however, received a 63% engagement and satisfaction score, and has been stuck in the lowest quartile of agency rankings in recent years.

“We used to be at the top of the surveys of Best Places to Work in the Federal Government, highest morale. We definitely are not now, in the past several years at least,” Rubin said. “This is a statement by the Congress and the administration of support for our people. It’s small, but when people see this, they say, ‘Actually, maybe they do care, at least a little bit. And maybe we can fix things that are broken.’ And that is potentially very important in convincing people either to join federal service, including the Foreign Service, or to stay.”

The previous lack of locality pay was also an issue related to diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility (DEIA). One of the underserved communities that President Joe Biden identified in his executive order promoting DEIA in the federal workforce is military spouses.

By establishing a locality pay equivalent under the 2023 NDAA, it’s a move in support of the EO aiming to advance equity for underserved communities, including to advance pay equity.

Some challenges remain for the DETO program

Obstacles still remain for Foreign Service family members looking to become DETOs.

Federal jobs that need access to classified information require DETOs to go through a lengthy and backlogged security clearance process.

Federal employees working with classified information overseas are also required to work out of U.S. embassies and consulates, rather than work from home. However, the State Department charges tenant agencies for office space their employees need to occupy overseas.

“There has to be space, and there isn’t always extra space. But the cost is very high,” Rubin said, adding that the cost can exceed $100,000 a year per employee. “If somebody is doing classified work and can’t work from home, it could be a nonstarter.”

State Department requires certain security measures if people are working for the federal government from their residences, but Rubin said generally the department has been supportive in making those arrangements possible.

“Every agency does have the right to decide whether they’ll allow it, and since COVID, they’re much more willing to allow it, in general, as are so many other employers. In my experience, people usually get approval, but not always,” Rubin said.

‘Embracing the digital transformation’ of work

Federal agencies comfortable with remote work and telework since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic have been able to recruit new employees beyond the Washington, D.C. area or other major metro areas.

But Foreign Service spouses are still an untapped pool of talent for the government, even though private-sector employers are recruiting them for telework-friendly jobs.

AAFSW for more than 30 years has shined a spotlight on the talents of Foreign Service spouses who are committed to ambitious projects, even when they aren’t currently in the labor market.

The Secretary of State Award for Outstanding Volunteerism Abroad typically showcases Foreign Service family members who make volunteer work a full-time focus, but are not formally employed.

Winning projects often reflect the professional background of the recipient. Last year’s award winners included a former engineer and a former financial services executive.

Erickson said the SOSA awards showcase the entrepreneurial mindset of Foreign Service family members and a commitment to public service. The State Department’s data, she said, shows the private sector is already tapping into this pool of talent, but not the government.

“We have so many talents at post ready to work, and that’s embracing the digital transformation of the workplace [and] teleworking,” Erickson said.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Drew Friedman is a workforce, pay and benefits reporter for Federal News Network.

Follow @dfriedmanWFED

Jory Heckman is a reporter at Federal News Network covering U.S. Postal Service, IRS, big data and technology issues.

Follow @jheckmanWFED

Related Stories