DOJ IG Horowitz reviews a decade of Bureau of Prisons crisis oversight

Having best places to work, means some employees endure the worst places. And the worst of all, according to the rankings for 2022 compiled by the Partnership f...

Follow the rest of Federal News Network’s series, The Worst Place to Work in the Federal Government.

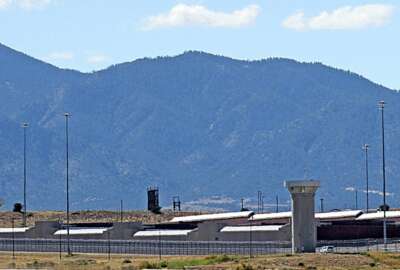

Federal Drive with Tom Temin launches a week-long series: The Worst Place to Work in the Federal Government. Having best places to work, means some employees endure the worst places. And the worst of all, according to the rankings for 2022 compiled by the Partnership for Public Services, is the Bureau of Prisons (BOP), a component of the Justice Department. It’s overall index of 35, compared to 55 for the Justice Department itself, is the lowest of any agency. And it dropped a statistically significant five points from the year earlier. Temin’s series starts with an overview of the BOP’s workforce challenges, with a discussion with Michael Horowitz, the Inspector General of the Justice Department.

Interview Transcript:

Tom Temin And just review some of the work in recent years you’ve done on Bureau of Prisons generally.

Michael Horowitz So we’ve done a series of reports about the Federal Bureau of Prisons, about challenges they have with their infrastructure and maintaining their infrastructure. There are a lot of aging prisons across the country. We’re talking about federal prisons now. We’ve done a number of reports about cameras in the BOP and the importance of effective cameras to prevent contraband from coming into the prisons, to prevent staff on inmate abuse, to prevent inmate on staff abuse, inmate on inmate abuse. Because when cameras aren’t there, problems arise. Contraband, big problem in the prisons and how to keep the contraband from coming in. Just a few of them.

Tom Temin And they all in some ways can impinge on the workforce because if the infrastructure is crumbling, that means the workplace is crumbling not just for the inmates, but for the people that have to go there every day.

Michael Horowitz That’s exactly right. I mean, whether you’re staff or inmates, you want to go to a building that doesn’t have holes in the roof, for example, or crumbling walls or bad infrastructure, just generally. Gyms, gym floors, broken, other things that are problematic, just one thing after another. People want to work in a place that’s a safe place to work.

Tom Temin And a lot of the issues come back to the staffing shortages, which is a management, I guess, shortcoming in being able to fill the positions that they’re budgeted for and authorized by Congress for. This came up in a report on recent one. You just did a federal correctional institution at Waseca. What is that? Where is it and what’s the issue there?

Michael Horowitz So Waseca is a all female institution in Waseca, Minnesota. Actually, the facilities where the inmates are housed was a former dormitory for University of Minnesota campus that was sold to the Federal Bureau of Prisons. And we did our first ever unannounced inspection. We showed up on a Monday morning at 8 a.m. We called the warden in the staff through to know we were coming at noon to do an inspection and we spent the week looking at the facility. We looked at we chose a female institution, all female institution, because we’ve have a huge problem with sexual assaults in prison on female inmates. We went to see how the prison was being run. The good news was it was generally well-run. The warden was very cooperative. The staff there was cooperative. The problem was the infrastructure, for example. We went in the kitchen. There was a hole in the ceiling and the roof, food had spoiled. The doctor’s offices had to be shut, at various points, because of infrastructure ceiling issues. Gym floor had been damaged. Things that we saw, we went to the dorm, basement dorms, pipes running along the ceiling, barely above the head of the top bunk, inmate, wrapped in plastic because they’d been leaking.

Tom Temin And this must be a minimum security type of facility if they even have those pipes within reach and that kind of thing.

Michael Horowitz That’s correct. And we chose Waseca because when we looked at our risk scoring model, Waseca was actually on the lower end, and since it was our first ever unannounced inspection, we thought, let’s choose a lower risk facility, one that likely didn’t have significant issues. Yet we saw the infrastructure issues and we saw huge staffing issues.

Tom Temin Yeah. Tell us more about the staffing issues. That is not enough corrections officers to cover the shifts properly.

Michael Horowitz Not enough corrections officers. One third of the positions were vacant, but not just corrections officers, doctors, health care professionals, mental health professionals, those were down 25-plus percent. And so you had this broad problem, and what it triggered was a cascading series of problems because you can’t leave a facility without sufficient correction officers. So what did it mean? Well, it mean, they put they pulled the facility staff and the educational staff off their regular duties to fill the correctional duties. They didn’t do that on the health care because those were already short staffed. So you ended up with facilities that needed fixing, having facility staff doing the other job, the corrections job. And you had education staff doing the corrections job. What did we find in the education space? Long waitlist for education and training programs.

Tom Temin Which gets back to the statutory requirement on the BOP for providing programs to help reduce recidivism.

Michael Horowitz And that’s exactly right. The First Step Act, a bipartisan bill passed in the prior administration, during the Trump administration, was all about training and and fighting recidivism and helping get inmates out of jail early through the right training. There were long wait lists and we weren’t confident that people were getting the kind of training they need.

Tom Temin Wow. And what did the staff tell you? Did you talk to line staff, people like the corrections officers and also the teachers and medical staff?

Michael Horowitz We did. And as you might expect, there was a frustration there. People want to do the jobs they were hired to do. Correctional officers want to have fellow correctional officers helping them staff the prison. They obviously appreciate the fact that education staff and facility staff come and work with them. But there’s a certain recognition that you can’t keep doing that, that you have to fill the jobs. And of course, education staff were hired to be educators, not correctional officers. And facility staff were there to fix the prisons. They weren’t pleased to have prisons crumbling around them. They couldn’t have time to fix.

Tom Temin Yeah, no wonder. I mean, imagine being someone who is there to teach or to administer in some other way and all of a sudden you’re on the floor and that happens across the prison system, not just at the low security ones.

Michael Horowitz It’s been an issue we’ve heard about for years, what’s called augmentation in the prison language, and we’ve heard about it. And this is one of the reasons we wanted to be on the ground. We wanted to see how much of that was there going on. And so we had an example, at least that this one prison of what it was.

Tom Temin We’re speaking with Michael Horowitz, inspector general of the Justice Department. And you mentioned there has been issues of improper sexual activity. As we speak, a former warden has spent his first weekend in prison for sexual abuse in California at a minimum security situation, plus five other staff members. How widespread is this and what’s your sense of the effect that that has on staff members that don’t participate in that kind of activity?

Michael Horowitz It’s a very significant issue. This is what you mentioned occurred at the Federal Correctional Institution in Dublin, California. The warden, by the way, the chaplain there, was convicted of sexual assault on female inmates, multiple other staff, as you mentioned. We have the cases are still going on. We are still investigating. That’s not the end of our work at that prison. But what does it say to an institution when the warden and the chaplain are both involved in sexual assaults on female inmates? And by the way, that’s not our first chaplain case in the last few years. We had a chaplain case in the Berlin facility in New Hampshire for contraband smuggling, not sexual assault, but contraband smuggling, which is another problem we’ve seen. And I think it’s fair to say that when you have thousands of honest, hardworking BOP employees who go to work every day wanting to do the job, wanting to make sure that they are not only making the facility safe and secure, but for many of them helping inmates rehabilitate. That’s the purpose that we want as well. Not just punishment, but rehabilitation. You can imagine if you go to a prison and your day job and you end up working alongside or in an institution where the warden or the chaplain is doing that sort of thing, or your fellow correctional officers are doing that sort of thing, that’s a debilitating place to be.

Tom Temin And as we mentioned at the top, the scores seem to drop precipitously when the COVID came in because you had just unprotected people with other unprotected people all mixing it. Officers work in close proximity to the inmates very often when they’re out of the cells. I mean, it can be literally crowded. No vaccines. They were slow to get personal protection gear in there. What what’s the sense of that whole situation? Are they past that and what kind of work did you do there?

Michael Horowitz So we we did two widespread surveys of staff in two different periods of time to see in 2020 or 2021 how they were reacting and reporting what their perceptions and observations were. And we actually just did our first ever inmate survey to see how inmate observations were and look at the two of them to see if we were seeing and hearing the same concerns. And as you indicated, you don’t do social distancing in a prison, right? It’s a crowded place. BOP facilities are generally close to capacity or beyond capacity. And so there’s not a lot of room to socially distance, as we all came to understand, trying to do that in 2020. And so you saw a lot of challenges for the BOP. They they didn’t have a playbook for this. They didn’t know exactly how to move forward with it. And so you had frustrations by staff having varying rules, availability of vaccines, questions about mask mandates or no masks, the questions for the issues for inmates as well, and the challenges there. How do we segregate out? How do we create a separate facility for COVID positive inmates and try and keep COVID negative inmates, COVID negative?

Tom Temin Sure. So you’ve had a drumbeat of reports over the years, as has the Government Accountability Office. And by the way, later in the week, we’re going to hear from Gretta Goodwin, the GAO resident expert, you might say, in the Bureau of Prisons. We also have a former inmate that’s going to be on the show who made it not only out of the supermax, but returned to productive life in society to this very day. Where is management in all this?

Michael Horowitz So that’s been the challenge, I think, frankly, for the BOP is to have sustained focused management on these issues at the leadership levels. I’ve been IG for 11 years. The new BOP director, Collette Peters, who came on board in August of last year, is the eighth confirmed or acting head of the agency since I’ve been there in 11 years. You don’t have sustained leadership. You’re going to have trouble coming up with the right budgeting, the right requests to OMB, the right engagement with Congress on these issues, let alone driving a culture into the organization. There are 121 wardens across the BOP. You need to have a team in place at the leadership levels. I mean, having a constant churn at the very top makes it very challenging. But what we’ve seen historically is a lack of a systematic approach to thinking about what kind of staffing do we need BOP-wide, what kind of infrastructure money do we need? Our infrastructure report showed that BP was asking for a tiny fraction of what it actually needed, even though it knew what it needed. We see staffing shortages in the health care area, mental health issues. The problem here is if you don’t have the right staffing for mental health, inmates don’t get better on their own. They probably get worse. Just drives costs up. You don’t fix facilities. Anybody who owns a house knows if you let a house continue to rot and be damaged, it doesn’t fix itself, right? It gets worse. Mold comes, other things happen.

Tom Temin Should the Bureau of Prisons directorate be a term appointment?

Michael Horowitz Well, it’s certainly something that’s worth considering, because having this change every couple of years isn’t working. There’s there’s really no ability to have sustained leadership. If every time there’s a new administration or something comes up, you end up with a new BOP director.

Tom Temin And in the day to day management on the ground, how do you deal with the fact that some prisoners are irredeemable, even though the majority might want to better themselves to get out and stay out?

Michael Horowitz Well, you have this question and this challenge I often talk about, which is in the federal prison system, there are very few inmates who will not get out of jail at some point. There are very few life sentences in the federal system. Whether you think sentences should be stronger and harsher or more lenient. Everybody can agree, at some point, inmates are getting out of jail. Everybody should agree that we want inmates to come out of jail, reformed to some degree, not made worse, but made better afterwards. And we want to cut down recidivism rates. And that’s the challenge and that’s the problem. If you have a disaffected staff there because they’re not getting the support they need, they’re not getting the staffing they need. They’re not seeing inmates get the medical care they need, the mental health treatment they need that cascades to everybody.

Tom Temin I mean, incarceration should be the punishment, but it shouldn’t be a sentence to further deterioration of your health and well-being. Mentally, physically, the incarceration itself constitutes the punishment.

Michael Horowitz Right I mean, it’s a dual purpose. It’s punishment, but it’s very importantly, rehabilitation. You want people to become more productive when they come out of jail, not angrier or suffering greater mental health issues because no one treated them. You often think about this. We hear about this every day, unfortunately, terribly now, about people with mental health problems on our streets. Well, when they’re in our jails, federal jails, for example, they’re in the federal government’s custody. There’s an ability to help and treat them. That’s a scenario that should be happening.

Follow the rest of Federal News Network’s series, The Worst Place to Work in the Federal Government.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Tom Temin is host of the Federal Drive and has been providing insight on federal technology and management issues for more than 30 years.

Follow @tteminWFED