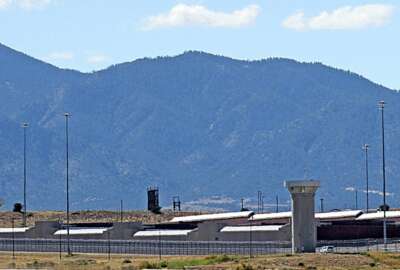

Do the names Robert Hanssen, Harold Nicholson or Walter Myers ring a bell? They have three things in common. All served as public servants in the national security apparatus, in the FBI, CIA and State Department respectively. All betrayed their country by selling secrets to U.S. adversaries. And all three live in a hellish place: The United States Penitentiary, Administrative Maximum Facility at Florence, Colorado, known popularly as ADX Florence.

One fact about ADX Florence: Cells, in which prisoners spend 23 hours a day, have a window four feet tall but only four inches wide. All an inmate can see is sky; not the Colorado Rockies, not a tree, not a road, not a building in the distance. If they could somehow squeeze through the slot, they’d have no idea where in the facility they’d land, so they could not know where to run.

The Bureau of Prisons (BOP), part of the Justice Department, operates ADX Florence and the collection of federal penitentiaries throughout the country ranging from the ADX to minimum security “Club Fed” facilities with no fences. One facility notorious for violence, Thomson Special Management Unit in Illinois, recently closed because it became unmanageable. Of course, that just scattered seeds of the problem to other prisons.

The Bureau is also distinguished for making not one, but two important lists in the last couple of weeks.

It ranked dead last in the Best Places to Work in the federal government, with an employee satisfaction index of 35. By contrast, the best sub-agency component, the Office of Negotiations and Restructuring at the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, got an index of 96.5. The PBGC itself averaged 87.6.

BOP also finds itself on the Government Accountability Office’s latest list of high-risk federal programs, a new addition to the biennial list. By coincidence, PBGC made it off the high-risk this year.

BOP has a paradoxical mission. It must incarcerate the worst of the worst in society, jailing people lacking scruples, who have committed all sorts of violence against public order or against other people. And yet, if you accept the notion that deprivation of freedom itself provides the punishment that our laws, society and culture decide is the consequence for law-breaking, then in some sense inmates join the nation’s most vulnerable people once they cross the threshold of the prison door. How it operates prisons and treats prisoners shows a government’s character no less than how it handles policing and judicial systems.

The work of prison guards — properly, correctional officers — ain’t like supervising kindergarteners. It comes with the constant potential for violent assault, even murder. Correctional officers, in theory, must simultaneously help prisoners rehabilitate and keep order in decidedly unorderly places. That’s a tall order.

Pay is low. Turnover is high. Many move on to better federal law enforcement jobs. Imagine the choice: Reporting to ADX Florence versus, say, Denver International Airport each day. At least TSA officers can stroll over to Panda Express for lunch.

The GAO’s point person on Justice, Gretta Goodwin, noted that BOP has more than 5,000 unfilled openings out of a staff authority of 40,000. This is after a hiring initiative the agency announced more than two years ago.

When a prison can’t fully staff a shift with regular officers, sometimes administrative or health people are dragooned into direct prisoner watching. Prisoners, she said, know when there’s a shortage or if someone unpracticed got assigned to the yard.

Staffing problems stem from the BOP’s general shortfalls in planning, programming, and program assessment capacity. For example, Goodwin said, the bureau is unable to provide a simple list of what it calls “unstructured activities” that accrue credits towards early release under the First Step Act. She wonders whether officials count staring at a cell wall as an unstructured activity.

Sustained leadership attention forms one point of GAO’s five-point strategy for improvement and eventually exiting the high-risk list. BOP has had six directors, including two acting, in six years. The latest director, Collette Peters, has met with Comptroller General Gene Dodaro to discuss the BOP’s problems. Presumably she’s also met with Justice Inspector General Michael Horowitz. His office late last year cited the same persistent problems as GAO has been following. BOP problems might require more money, but they require a new culture even more.

Here’s how BOP states its own mission: “We protect public safety by ensuring that federal offenders serve their sentences of imprisonment in facilities that are safe, humane, cost-efficient, and appropriately secure, and provide reentry programming to ensure their successful return to the community.”

It’s time to really do that, for the inmates, the employees and the public.

Copyright

© 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.