Recent upticks in Defense spending have meant a larger portion of the budget pie goes to contractors. But R&D contracts still haven't recovered from sequestrati...

The last few years of increases to the Defense budget have been, in general, good news for contractors. But it’s an uneven picture.

In particular, Pentagon spending on research and development still hasn’t recovered from the cuts imposed by the 2011 Budget Control Act even as spending on products and services has risen significantly.

Those findings are part of the latest annual analysis of DoD contract spending data by the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Overall, CSIS found contract spending has risen 35% since 2015, the low point of the Defense drawdown. That figure includes a 4% increase between 2018 and 2019.

But when it comes to R&D spending, the recovery has been much, much slower. In 2019, the department spent about $30 billion on R&D contracts. That’s well below what it spent in 2012, and even adjusting for inflation, about the same as pre-9/11 level spending.

“The bigger picture in this recovery is that products have had the lion’s share, and services have come on in the last couple of years,” said Andrew Hunter, the director of the Defense-Industrial Initiatives Group at CSIS. “R&D did well in FY19 in percentage terms, but it really was the first year that we saw substantial growth in R&D contracts.”

And spending growth in the later stages of the R&D process has been especially anemic, the new analysis shows.

Historically, Hunter said, the most expensive portion of DoD’s R&D accounts has been the System Development and Demonstration (SDD) phase, after technologies have already been prototyped and are being put through their paces. But SDD spending has been essentially stagnant for the past five years, even as the Defense budget has grown significantly.

“It’s now one of the smallest categories within the R&D portfolio, and it has not been growing. It’s a small and shrinking share,” Hunter said. “What we see is the department moving away from the classical Defense acquisition approach with a heavy emphasis on what we used to call engineering, manufacturing, and development. One of the questions is whether this is going to stay a sort of dormant, stagnant sector of the R&D account. And if it doesn’t, what does that tell us about where we’re headed in the acquisition system?”

Where the R&D budget has seen growth is in the prototyping phase. Spending on the Advanced Component Development and Prototypes portion of the budget has shot up 73% since 2015. And Hunter said that doesn’t include DoD spending on other transaction agreements (OTAs), which are predominantly used for prototyping.

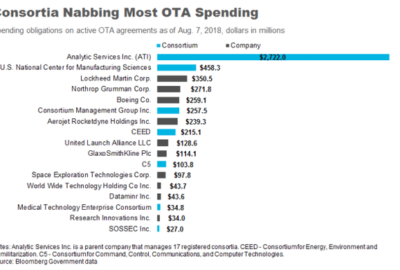

The new analysis also makes clear the extent to which DoD’s use of other transaction agreements has skyrocketed since 2015, when Congress gave the department new authorities to use OTAs. OTA spending rose 712% between 2015 and 2019, hitting a total of $7.7 billion; 82% of that figure went toward research and development.

But the data shows the military services and Defense agencies have increasingly been using OTAs to buy products and services, too, with $9 billion in spending in each of those categories last year.

“Things like cloud computing and AI could potentially register as OTAs for services,” Hunter said. “And for products, we’re starting to see things like launch systems, and other potentially in the future helicopters and vehicles procured under OTAs. That growth is notable even though they’re still overwhelmingly used for R&D purposes.”

Hunter said he believes the majority of that OTA spending is going to nontraditional companies, since the Defense Department still prefers to use traditional contracts anytime it’s dealing with a large Defense contractor who can navigate the rules of the Federal Acquisition Regulation.

But it’s hard to know for sure, because the majority of OTA dollars are being awarded to industry consortiums, not directly to companies. Theoretically, a “significant” share of the work inside those consortiums is supposed to be done by “nontraditional” Defense companies.

“But it’s hard to know how much is ‘significant.’ Is the nontraditional the recipient of the OTA, but maybe there’s a bigger company that stands behind them? Is the nontraditional part of a team? The actual OTA holder may be a prime contractor,” Hunter said. “[Within the consortiums,] it’s hard to tell who’s doing the actual work, because we know the consortium is not doing the work.”

Even though R&D spending still hasn’t caught up with historical norms, overall, an increase in the Defense budget has been good for contractors.

The data show spending on Defense contracts has grown 31% since 2015. And as of 2019, as a share of the Pentagon budget, contracts made up 55% of the department’s total budget authority. CSIS found that’s the third highest level in the past 20 years.

“It tends to oscillate between the high 40s and the mid 50s, and the fact that we’re at a relatively high historical share suggests to me that we could be starting a move in the other direction, and the pendulum could swing back,” Hunter said. “If budgets flatten or potentially go down, contract obligations could revert to the mean, which would mean a larger reduction in contract obligations. That is what happened when we had sequestration. The budget drawdown as the share of budget going to contracts fell significantly — industry bore a larger share of the cut than other costs within the Defense budget.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jared Serbu is deputy editor of Federal News Network and reports on the Defense Department’s contracting, legislative, workforce and IT issues.

Follow @jserbuWFED

Exclusive

Exclusive