The infrastructure bill includes money for reducing infrastructure

When you think infrastructure, you probably think of new and replacement. But the big bill enacted late last year also has money for removing infrastructure.

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

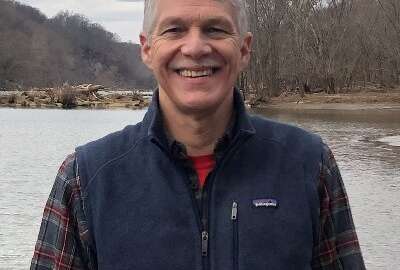

When you think infrastructure, you probably think of new and replacement. But the big bill enacted late last year also has money for removing infrastructure. Specifically, river dams. For how and why this is the case, the Federal Drive with Tom Temin spoke with Tom Kiernan, the president and CEO of the non-profit American Rivers.

Interview transcript:

Tom Temin: Mr. Kiernan, good to have you on.

Tom Kiernan: Great to be with you, Tom. Thank you for having me.

Tom Temin: And let’s begin with the mission of American Rivers, you advocate on behalf of rivers in what way?

Tom Kiernan: Well, we’ve got three main goals to protect wild rivers, to restore damaged rivers and to conserve clean water. So it’s about having healthy rivers that we and wildlife can enjoy, and also to have clean drinking water.

Tom Temin: All right, and restoring rivers then, in some cases, requires removing dams. And tell us about the infrastructure bill and how that enables removal of dams.

Tom Kiernan: We have hundreds of thousands of dams in this country, only about 3% of them actually produce hydro-power, produce electricity. So 97% of all the dams don’t produce electricity, and many, many of them are outdated or abandoned. And they are causing significant harm to the rivers, it prevents fish from migrating up and down the river, prevents clean water from moving down the rivers and allowing the river to be healthy and resilient. So there is fortunately $800 million in the bipartisan infrastructure law that was passed and signed by the president for removing dams. And the federal government is stepping forward to partner with state governments and local groups and companies to begin removing a lot of these outdated, abandoned, very harmful dams.

Tom Temin: Yeah, almost every rural town you go through, you know, has a river, because that’s where towns were built. And there’s a little dam there in the middle of town next to the bridge, and I’m seeing how it’s hundreds of thousands that you mentioned. But what’s the process by which a given dam, which is not a federal facility, could be slated and everyone agrees to remove it? How does that happen?

Tom Kiernan: It’s not easy, it is pretty complicated, we do end up needing to get whether some local permits, or state permits, or in some cases, dams are owned by the federal government. So you’ve got to work with a lot of partners and local stakeholders. But at the end of the day, you end up with a river that is alive, that is resilient, we are having as we’re seeing every day now more floods and more droughts, given climate change. And the best thing to do is to have a river that is functioning, that is healthy, that is flowing, that has its wetlands or its floodplains. So removing a dam, it’s kind of like think of the rivers in the country as your vascular system, your arteries and veins in your body and the dams as kind of coronary artery disease blocking them. So the best thing to do for the health of the country is to remove these blockages, these dams on so many of our rivers. And so that’s what American Rivers and our partners are doing throughout the country. And we’re pleased with Congress and the president for that $800 million to help support this dam removal renaissance, if you will.

Tom Temin: And you mentioned some of these dams are quite old, I mean, that they used to call infrastructure at one time, the term was internal improvements, I think was the word in the United States. And they must have been built for a purpose.

Tom Kiernan: Yeah.

Tom Temin: Tell us about why some of them may have been built, and why they no longer are needed.

Tom Kiernan: It’s a great point, Tom, because a lot of these dams were built, maybe for irrigation purposes or to power, especially in the Northeast textile mills, well, the mills are long gone. But the dam is still sitting there, because it’s frankly, just abandoned, it’s sitting there and nobody has taken it down. So the dams likely were built for good reasons back in the 1950s, or whenever, and that reason has long passed. So it’s important that we invest in clean rivers and natural rivers. So that’s kind of the new infrastructure, if you will, and that is removing these dams that are harming the rivers. And they’ve long since outlived whatever purpose they had back then. You know, some people will see a dam and, and in some cases, there is interesting, important history to it. But in a lot of cases, the best thing to do for the community, for recreation, for health of the river and for clean drinking water, we get 70% of our drinking water from rivers. So the best way to ensure clean drinking water is to remove these outdated dams and allow the river to be clean and allow the fish to migrate so that they, too, can have accessible healthy habitat.

Tom Temin: We’re speaking with Tom Kiernan. He’s president and CEO of American Rivers. And you’ve done a great job of describing the river flows. What is the money flow from what Congress appropriated into whose hands does it need to get and how does it get there for the eventual removal of dams?

Tom Kiernan: There are a number of different federal agencies involved. So some of the money Congress appropriated went to or is going through the Fish and Wildlife Service, some of its going to NOAA, some of it, a little bit of it to EPA, or the Bureau of Reclamation or the Corps of Engineers. So it kind of is going to a number of these different agencies and groups like American Rivers. Also state governments are working with the federal government to now prioritize which dams to remove.

I should say, we have removed about 2,000 dams in the last 20, 30 years, we removed 57 dams this last year in 2021. So we are looking to increase the rate of dam removal because as I said, we’ve got hundreds of thousands of dams causing a lot of damage throughout the country. So we do need to pick up the pace, and frankly look for more involvement of the American public and policy leaders. Because with climate change, we need healthy, resilient rivers to better manage the floods and droughts that are coming.

Tom Temin: And another practical question in many towns and locales, small cities, I’m thinking of like Ellicott City, Maryland, for example, a lot of infrastructure of commercial type has built up next to control rivers. How do you mitigate what could happen to them when suddenly, the dam that gave rise to that development is removed?

Tom Kiernan: What’s interesting, one of the things we also work on is restoring wetlands and restoring floodplains upstream of some of those urban centers. And one of the best ways of controlling flooding downstream is to have wetlands that are functioning and floodplains that are functioning upstream. Because what happens if there’s a big rainstorm, one of the best ways of holding that water back is with wetlands and floodplains, those soggy areas actually store an awful lot of water. And then what they do is they slowly release it during the summer, when you’ve got all these concrete, whether it’s a dam, or concrete levees or barriers, that actually allows the water to come ripping through all at once, and flood towns and cities. So it’s the natural infrastructure, the wetlands, the floodplains that do the best, frankly, most cost-effective job at retaining water so that we don’t get flooded out downstream. And, you know, water managers, we’ve learned this over the last several decades that just building more concrete and more dams, actually is harmful, not helpful. So we’re kind of now relying on Mother Nature to slow down the water and to reduce the damage from flooding and drought.

Tom Temin: And does dam removal, the whole field, include also removal of those rivers that are encased in concrete, like in Los Angeles?

Tom Kiernan: You know, it’s funny to say that, we are working more and more with communities like Los Angeles with the Los Angeles River that is, you know, in many cases, just kind of a concrete culvert or a concrete sluice way, and restoring some of the natural systems and what’s also wonderful to see the communities, the people living next door then can get out there walking along the river or fishing even or even swimming in it where, you know, if it’s just concrete tube, you’re not fishing, you’re not swimming, it’s not pretty, it’s not relaxing. So replacing those concrete rivers, restoring with a natural environment makes ecological sense, better water quality, but also for the communities. You know, we live stressful lives these days, and it sure is a lot more pleasant to walk along a relaxing, wooded riparian area next to a river and people are seeing that personally stress reducing to enjoy a natural river through their urban area.

Tom Temin: So if I want to lay down some rubber on a dry concrete riverbed, I better do it soon.

Tom Kiernan: If that were your goal, we would again though, hope people would support natural systems, natural rivers, because it’s what’s best for all of us. Both for nature, but very much for communities.

Tom Temin: No Grease reenactments, please. And just a final question, in all of this removal is the Hoover Dam safe?

Tom Kiernan: There are big dams that are producing a lot of electricity, you know, the Hoover Dam is not going anywhere. It is there. It is safe. However, you mentioned Hoover Dam and Lake Mead and Lake Powell. We are at record low levels on those lakes because of the drought in the Southwest. So here again, we do need to care for that, in that case, the Colorado River and work to restore its headwaters, and better manage it. Our rivers, I mean they are the lifelines, the lifeblood of our continent. And we’ve got to do a better job taking care of our rivers because again, we rely on them for, yes for wildlife and habitat but 70% of our drinking water comes from these rivers so we’re going to get mighty thirsty if we don’t do a better job of taking care of our rivers.

Tom Temin: Tom Kiernan is President and CEO of American Rivers. Thanks so much for joining me.

Tom Kiernan: Thank you, Tom. Good to be with you.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Tom Temin is host of the Federal Drive and has been providing insight on federal technology and management issues for more than 30 years.

Follow @tteminWFED