FedRAMP’s banner year leads to more ideas to speed up, improve the processes

The Center for Cybersecurity Policy and Law, a nonprofit focused on federal cyber policies, released a white paper with three recommendations for how to improve...

You have to wonder if Ashley Mahan and her co-workers running the Federal Risk Authorization and Management Program (FedRAMP) ever feel like they can make anyone happy.

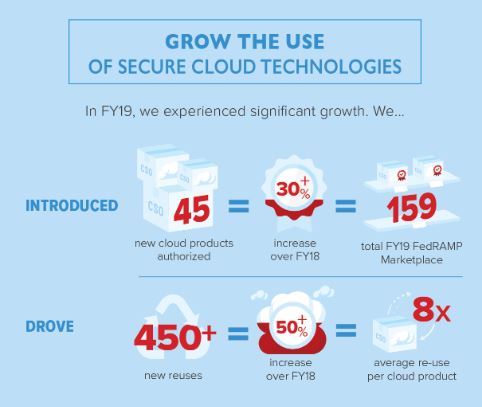

Despite a record fiscal 2019, which saw a 30% increase in the number of cloud services authorized and 50% increase in the number of cloud products reused across the government, industry, Congress and agency customers want more.

Oversight and Reform Subcommittee on Government Operations Chairman Gerry Connolly (D-Va.) and Ranking Member Mark Meadows (R-N.C.) saw their FedRAMP Authorization Act of 2019 pass the House on Feb. 5. The bill is now before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee. Among the things the bill would require is for agencies to provide a “presumption of adequacy” to vendors that have already gotten FedRAMP-certified at other agencies.

Agency chief information officers and other technology executives publicly praise FedRAMP, but privately don’t trust the authorizations in the way the Office of Management and Budget originally hoped they would. Just take a read of this December 2019 Government Accountability Report, which found 15 agencies reported that they did not always use the program for authorizing cloud services, for a bit more evidence of this public-private disconnect.

And now a non-profit led by former Office of Management and Budget and National Security Council executives have issued a white paper with recommendations to move FedRAMP to the next level—as a risk management and continuous monitoring program.

The Center for Cybersecurity Policy and Law, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting education and collaboration among industry and policymakers on policies related to cybersecurity, say the program, which OMB and the General Services Administration launched in June 2012, is no longer the best approach for the current security needs of today.

“It is unsuited to the growth of emerging technologies like internet of things (IoT) and artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML) and is not dynamic enough to incorporate new innovative products,” the white paper states. “These deficiencies are a result of FedRAMP’s limited resourcing and ability to keep pace with agency and cloud service provider (CSP) demand for review and authorization, agencies’ limited reuse of authorizations to operate (ATOs), and the compliance focused, manually driven certification and maintenance process that underpins the interaction between agencies and CSPs. These deficiencies create an opportunity to revise FedRAMP in a manner that reflects a maturation of the government’s risk-management approach and improves IT modernization outcomes.”

Read more: Reporter’s Notebook

The group’s three recommendations focus on how to improve not just FedRAMP, but federal cybersecurity more broadly:

- Redefine federal IT risk management, including FedRAMP, to place continuous, incremental and automated monitoring at the heart of the process.

- Consolidate and standardize the process for risk acceptance across the federal government.

- Enable the federal government to leverage the full scope of emerging innovation in the cloud computing and information technology markets.

Ross Nodurft, who works with the Center for Cybersecurity Policy and Law, said in an interview with Federal News Network that the center has been working with the FedRAMP team at GSA and have a commitment from them on how to move forward from a tactical perspective.

“Our plan going forward is to continue to socialize the recommendations and ask for feedback about how to do it tactically,” Nodurft said. “Both the cloud service providers and agency folks have a lot of different ideas of how to do it. What we need to do is push this paper into the conversation at the agency level. We will ask at a more tactical and granular level how the practitioners think the best way to move forward is. We have ideas ourselves, but we want to make sure we are continuing to engage in that conversation.”

One way to do that is to take the subjectivity out of FedRAMP. Yes, there are standards that every CSP must meet to receive authorizations, but how agencies interpret the certifications is many times where the problems exist.

Nodurft said one way to take out the subjectivity is to mandate standardized configuration settings, which would also help the automation tools to confirm the CSPs are meeting the security requirements of the system.

“It takes the human judgement out of compliance, and that is a big part of it,” he said. “We also have to create the policy environment that builds the trust pathways. We have to look at shared services. We have to look at systems that are similar across agency environments and we have to identify the standard configuration settings and point to them and say ‘it’s OK for you to adopt the work done by one agency and by one authorizing official.’ We have to work with oversight officials whether it’s from an inspector general to identifying good practices or OMB tweaking a policy to say ‘you shall do this more,’ or whether it’s Congress holding up and highlighting good use cases for agency ATO reuse and tracking how much of that reuse is happening, it has to be top down and we have to take as much as the human decision making process out of it to speed this up.”

Speed always has been a bugaboo for FedRAMP. When the program first started, it would take 12-to-18 months to get a CSP through the process. Now, it’s down to 9-to-12 months, and in the case of FedRAMP Accelerated, much quicker.

The center, however, says in its report that the speed of change in the threat landscape as well as the emerging technologies require a better approach.

“Through the mechanisms we have now for interagency discussion, there is an opportunity to identify those use cases, hold them up and say ‘agencies you shall do this when you can, default to reuse first,’ which is a shift in the risk ownership, or we can be softer and say, ‘we encourage you to do this. We’ve recognized people who have done this well and here are the current best practices,’” he said. “We have to continue to promote this and drive agency thinking. I think they should take a hard look at both approaches.”

Nodurft said the first recommendation is about bringing speed to the process by placing the continuous, automated and incremental monitoring at the heart of the process.

“Under that, we had four sub-recommendations. We need to identify those FedRAMP controls that can be automatically assessed for all systems. We need to continue efforts to develop fully automated standards for security assessments,” he said. “We need to update the FedRAMP secure assessment framework to make it consistent with the NIST cybersecurity framework. We need to develop dashboards for the real time monitoring in government cloud environments.”

FedRAMP’s evolution continues

Joe Stuntz, director of federal and platform for Virtru and a former OMB chief of the cybersecurity and national security unit, said the white paper frames the challenge correcting around redefining IT risk management.

“FedRAMP gets a lot of feedback as the public face of Cyber and IT risk management in government, but many of the challenges of the FedRAMP program are due to risk management requirements and especially the ATO process so only addressing FedRAMP will not lead to faster and more effective authorizations of technology for federal agency use,” he said. “The focus on reuse and possible shared services is good, but these initiatives will run into the fundamental challenges around ATOs and risk acceptance. This paper can’t solve these broader challenges and the incentives involved that lead to more risk avoidance, but by improving FedRAMP, it will hopefully drive change in the broader risk management processes.”

Read more Technology news

To be fair, Mahan and her colleagues have not sat idly by and watched the world around them change. FedRAMP listens to industry and agency customers, implements updates and continues to evolve the requirements. The best examples are the FedRAMP Accelerated process for systems that do not require moderate or high levels of security. It also recently began work with the National Institute of Standards and Technology and industry to develop the Open Security Controls Assessment Language (OSCAL), a standard that can be applied to the publication, implementation and assessment of security controls.

Nodurft said the development of the OSCAL standard is something that could produce the near-term improvements for agencies and CSPs alike.

Over the long-term, Nodurft said the real goal is to change how agencies accept risk. He said since the 2015 cyber sprint, the overall trend for agencies has been to accept less risk.

“We need to continue to push the innovation message and continue to hold up the people who are embracing the innovation and the risk that goes along with the innovation and not penalize them for doing that,” he said. “That is extremely important for this conversation.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED

Related Stories

FedRAMP, MGT Act reforms on Rep. Connolly’s radar after August recess