NIST will finalize new publication NISTIR 8276 that will include eight key principles for protecting IT supply chains and release the draft to update SP 800-161...

The rising call to protect agency technology supply chains isn’t new. Back in 2012, the Senate Armed Services Committee released an eye-opening report on counterfeit electronic products in the Defense Department.

The Pentagon has been aware of counterfeit and supply chain problems dating back decades, but saw a huge upswing in these parts infiltrating its national security systems starting in 2005.

The recent SolarWinds cyber breach brought to light not only how complicated this challenge is but the need to stop staring at the problem and take real action.

Over the last few years, agencies have done a lot of thinking and planning with the development of the Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC) standards and the creation of the Federal Acquisition Security Council (FASC) to name a few, but real change has been hard to come by.

Jon Boyens, the deputy chief of Computer Security Division at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, said a 2018 report by the Ponemon Institute found 66% of companies do not have a comprehensive third-party inventory. The 2019 Ponemon report found the average cost of a supply chain attack was $7.5 million and more than 50% of all respondents reported a breach in the two years.

“Even now, when we talk about supply chain risk management, it’s kind of a level set. It means different things to different people. Some people still do not get the relevance of it or they look at different aspects very adversarial,” Boyens said at a recent supply chain event sponsored by FCW.

This is why many believe the SolarWinds supply chain breach finally will get the government and industry to act more decisively and quickly.

Rep. John Katko (R-N.Y.), the ranking member of the Homeland Security Committee, explained this desire to take real actions and not just stare at the problem in a Jan. 19 letter to the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency in the Department of Homeland Security.

“I remain concerned that the Federal Acquisition Security Council is not making rapid enough progress to operationalize its ability to leverage its authorities from the SECURE Technology Act,” Katko wrote to acting CISA director Brandon Wales. “It is our understanding that CISA is currently developing the analytical framework that will help guide how risk judgements are considered by the FASC. As a member of the council and the designated information sharing agency of the FASC, it is incumbent on CISA to ensure that all recommendations take into account the wide range of potential attack vectors to the supply chain. Recent revelations about the cyber campaigns against SolarWinds and other entities have reinforced the foundational importance of secure software for overall information and communications technology (ICT) supply chain risk management. Accordingly, specific attention should be given to software assurance and software development lifecycle considerations as part of the analytic framework behind FASC recommendations.”

The FASC has been more than two years in the making. President Donald Trump signed the Federal Acquisition Supply Chain Security Act of 2018 into law as part of the Secure Technology Act. The council finalized its strategic plan, its charter and issued an interim rule detailing how it will share supply chain risk information and recommendation removal or exclusions of specific products or technologies.

Katko asked for CISA to give the committee its timeline to operationalize the information sharing framework no later than Feb. 1.

His letter also demonstrates the need for the FASC, CISA and many others around government to move more quickly to address supply chain challenges.

A Government Accountability Office report from December shined a brighter light on this issue of doing something rather than just talking about it.

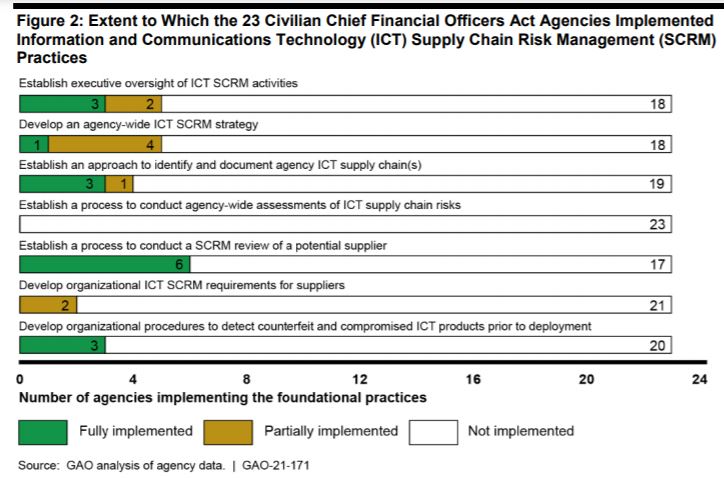

Of the seven best practices to protect the technology supply chain, GAO says few of the 23 civilian CFO Act agencies implemented them.

“[T]he potential exists for serious adverse impact on an agency’s operations, assets and employees. Nevertheless, the majority of the 23 agencies had not implemented any of the seven selected foundational practices for managing ICT supply chain risks,” GAO stated. “These practices included establishing executive oversight of ICT SCRM activities, developing an agencywide SCRM strategy, and establishing a process to conduct agencywide assessment of ICT supply chain risks. Among those agencies that had implemented any of the practices, none had fully implemented all of them.”

Boyens and others say while agencies are taking steps in the right direction, the government needs to implement key practices and principles to make progress more quickly.

NIST is outlining those eight key principles in a new publication NISTIR 8276. Boyens said he expects NIST to finalize the document in the next two to three weeks as it’s currently in the formal NIST review process. The agency released the draft 8276 for comments in February 2020.

He said among the key principles NIST will include are recommending agencies establish a former SCRM program to help decide which requirements will flow down to which suppliers, how best to assess and monitor the supply chain and create relationships with and manage key suppliers.

“Sometimes a lot of the political and economic aspects get into SCRM and blurry the water a little bit, which is why trustworthiness is so important. Do I have a level of confidence that makes me think the other entity is trustworthy,” Boyens said. “A lot of that can be basic due diligence. How does the business conduct itself? Are they reliable? What are the confidence building mechanisms we can use? We rely heavily on standards and conformity assessment procedures to get us to that confidence level.”

NIST also will release the updated draft Special Publication 800-161 for supply chain risk management in the next month or two. The agency hasn’t updated the publication since 2015.

“In that publication, we are putting in key practices for cybersecurity aspects of supply chain risk management from a government perspective,” he said. “It’s mostly likely going to have a lot of aspects of NISTIR 8276, but it will be tailored to the U.S. government and our constraints.”

Boyens said it’s clear agencies can’t be 100% sure that they are receiving a trustworthy system. Instead, agencies need to make sure they are resilient and continue mission functions in the event of a breach.

“System security engineering is a key component to that, building resilient architecture and systems. That is where a lot of this is fundamental in cyber supply chain risk management,” he said.

CISA also has been active in the supply chain risk management space through its ICT Supply Chain Risk Management Working Group, which released its year two report in December highlighting six initiatives it worked on during 2020.

Among its deliverables in 2020 were the creation of a vendor SCRM template, which are a standardized set of questions to communicate ICT supply chain risk posture and analyze comparative risk among all types and sizes of organizations, to enable increased transparency in managing ICT outsourcing risks, and a threat evaluation working group. That committee conducted an assessment of threats to and from products and services, evaluating those threats with a scenario-based process. It also created a risk and mitigation resource by leveraging threat groupings and applying the National Institute of Standards and Technology Risk Management Framework described in NIST SP 800-161.

Bob Kolasky, the director of the National Risk Management Center at CISA, said at the FCW event that the task force will release its second version of the threat evaluation guide in the next week or two.

“The task force identified a couple hundred reference threats to the supply chain, including exploitation, physical and cyber threats,” he said. “The guidance will serve as a reference for risk managers so they can identify where their priority threats are and match them with vulnerabilities to their systems.”

He said government, industry and others downloaded version one of the guide 14,000 times in the year since the task force released it.

Few would argue that working groups and guidance aren’t important and help lay the ground work for good work, but agencies and industry should know what the problems are by now when it comes to supply chain risks and should start fixing them.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED