The suspension, debarment process could be improved, but not by DoJ taking the lead

Federal contracting experts say Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Ben Ray Luján (D-N.M.) letter to the Justice Department misses the mark on how to improve the...

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

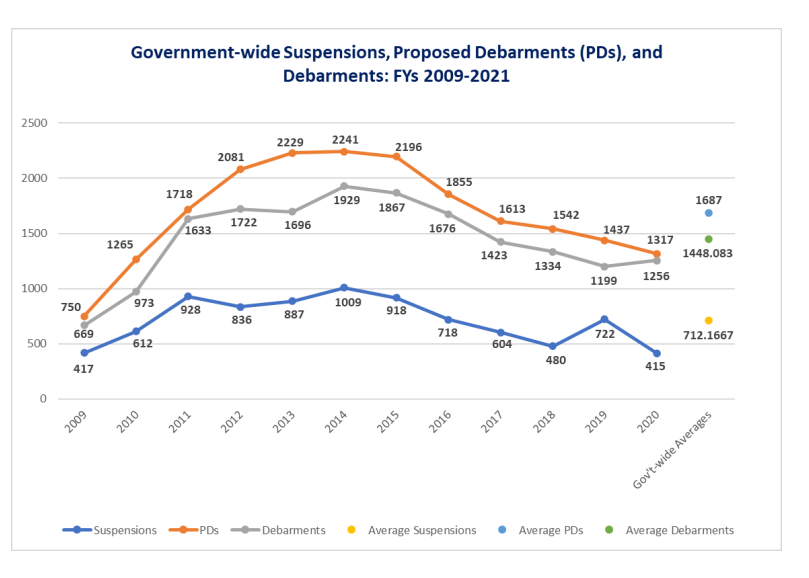

The number of contractors suspended and debarred hit a 12-year high in 2014 with 1,929 vendors or executives debarred and another 1,009 suspended from federal acquisition.

Compare those numbers to what the Interagency Suspension and Debarment Committee reported in its fiscal 2020 report released earlier this year: 1,256 companies or executives debarred and 415 suspended.

That’s a 34% drop in the number of debarments and a 59% reduction in the number of suspensions.

Now take into account the amount of money spent on federal procurement has increased to $665 billion in 2020 from $448 billion in 2014 — a $217 billion or 32% increase.

By raw numbers alone, more money going out the door and fewer contractors doing bad things that would require agencies to take these extraordinary actions may not compute.

This is some of the logic probably used by Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Ben Ray Luján (D-N.M.) in a recent letter to the Justice Department seeking it take a more aggressive suspension and debarment position.

“The department has broad authority to debar any government contractor that has committed a covered violation as long as the department follows proper referral and debarment procedures. Notably, the department can debar even companies that it does not directly do business with, and a contractor can be debarred even for conduct that does not relate to any of its government contracts,” the senators wrote in their Aug. 11 letter to Attorney General Merrick Garland and Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco. “The department’s historically lethargic use of its debarment authority sends a clear message: Corporate criminals can engage in any kind of wrongdoing, and — after receiving an occasional fine or slap on the wrist — can return to business as usual, receiving millions (and in some cases, billions) in taxpayer-funded government contracts. Corporate criminals and their top executives can rest easy knowing that no matter how egregious, how extensive, or how long-lasting their misconduct, the government will welcome them back to the contracting table with open arms. It is time for this lax approach to change. The department’s prosecutors and procurement staff should use all the tools at their disposal, including suspension and debarment, to deter corporate criminals.”

Warren and Luján offered four ways DoJ could be more aggressive, including taking on a governmentwide role for debarring contractors.

Letter is missing broader issues

The letter received a lot of attention in the contracting community. Some of it in mocking praise, where experts offered comments like “it’s great the senators are paying attention to federal contracting, but maybe they should read the suspension and debarment regulations first.”

Some of it in bewilderment about what suspension and debarment is and why agencies tend to use it.

“They are asking that Justice adopt a role that it hasn’t historically done. DoJ has suspended and debarred contractors who deal with DoJ, but what this letter is asking them to do is adopt role of super all-encompassing S&D authority for the government,” said John Chierichella, the CEO of Chierichella Procurement Strategies and a long-time federal procurement lawyer. “What that would do is put the authority into the hands of agency that may not be, and probably will not be, the agency that was the ‘victim’ of the underlying wrongdoing. DoJ is not the agency that will suffer the consequences of having a contractor excluded of providing goods and services to that agency.”

He said politicians who make these types of proposals should pay attention to the standards for suspension and debarment in the regulations.

“That is what is missing from this letter,” he added. “What I believe is that if we would follow this new policy that the senators want to impose, you would see an agency whose role is what? Prosecution. They look to punish people. That’s their role in life. They will go out and apply this broadly and they will look to punish contractors and they will not understand the people who need these companies to perform this mission.”

Other federal contracting experts echoed Chierichella’s comments, saying Warren and Luján are missing the broader rationale for suspension and debarment.

Not a punishment, but a protection

Time and again lawyers say suspension and debarment is not a punishment, but a way for agencies to protect themselves. Even the interagency S&D committee makes that point in a recent document dispelling misconceptions about suspension and debarment.

Question: Can the suspension and debarment remedy be used for punishment or penalties, or as an enforcement tool?

Answer: No. The suspension and debarment remedies are used prospectively to protect the government’s interests and assess business risk.

Robert Burton, a partner with Crowell & Moring and a former deputy administrator in the Office of Federal Procurement Policy, said generally speaking, the suspension and debarment process works well. Both as a deterrent and as a way to protect agencies.

“If a company has taken corrective action and maybe entering into a civil settlement, most agencies find it hard to punish them further because that has been done by criminal or civil authorities,” Burton said. “Since it’s not a punishment tool, does the government need to be protected from an entity after the company took corrective action and put in internal controls to prevent issues in the future?”

Chierichella added when agencies put the suspension and debarment standards in contracts, vendors took note. He said companies tend to rectify any potential or real problems to prevent themselves from receiving what many refer to as the “death penalty.”

“These regulations have been effective and companies pay a lot of attention to this list of factors that determine whether they may violate rules that could get them suspended or debarred,” he said.

Burton and others say the government has a lot of tools at their disposal to punish contractors for poor performance on a contract or for other issues.

Eric Crusius, a procurement attorney with Holland & Knight, said agencies can terminate a contract, write a negative past performance review, both of which should have a desired effect that doesn’t potentially harm the future of a company and their employees.

“The agency that contracts with the contractor often has the best insight of the contractor’s conduct and present responsibility,” he said. “Further, the contracting agency best understands the practical implications of a debarment, like is the company vital to their supply chain?”

Crusius said Justice would have no insight into those details, which could cause bigger problems for agencies.

Ways to improve S&D

The suspension and debarment process is far from perfect, experts say.

Barbara Kinosky, the managing partner of Centre Law and Consulting, said agencies too often go after small businesses because they have fewer resources to fight back.

She said the senators correctly pointed out that cases against companies like Balfour Beatty or Schneider Electric are much more difficult to win than those against small businesses.

“I have been retained, as an expert witness, in several matters that involve False Claims Act issues and suspension or debarment. I have noticed from my experience that DOJ appears to prefer proceedings against small businesses who do not have the legal budget to hire platoons of attorneys,” she said. “I suspect that Balfour Beatty has the luxury of having lobbyists on Capitol Hill, something most small businesses do not have. And let’s add to the mix, how difficult it would be for the military to find another contractor for badly needed housing. On the record it appears that Balfour, a repeat offender, should be debarred. And so should Avanos Medical who put medical lives at risk. But Avanos just reported operating profit of $46 million. So I ask the question, who is the easier target?”

Burton said if there was one area where DoJ could be more helpful around suspension and debarment, it would be how they share information with agencies.

He said there are cases where agencies need to take protective action and issue a suspension but can’t because DoJ prosecutors will not share information during an investigation.

“It’s important to understand that the idea of ‘adequate evidence’ is a low bar. DoJ doesn’t have to show everything, but some things would be incredibly helpful while not compromising an investigation,” Burton said. “The senators make a good point that there could be more activity in this whole area in respect to protecting the government. The numbers are rather surprisingly low, especially in view of problems we’ve seen with fraud regarding grant money through the American Rescue Plan Act. Agencies have been overly cautious and maybe in some instances S&D could be used more widely to protect government.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED

Related Stories