The "women inventor rate" is rising but it's still mysteriously low, a U.S. Patent and Trademark Office study found.

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

Plucky Junie B. Jones, of children’s book fame, got to help her dad repair the toilet and see how the mechanism worked. To Junie the occasion was a “dream come true.” When my daughter was very young, we used to howl with laughter over that line. On one occasion the dream came true in reality, when I had to replace the works on one of the toilets in our own house.

My daughter grew up to be more business management-oriented, not so much into mechanics and engineering. But the “dream come true” came to mind when I read some facts the other day. Between 1790 and 1859, the United States granted 32,362 patents to men but only 72 to women. The numbers of patents ballooned as the industrial revolution proceeded. Women’s participation in the inventing fields has steadily increased, but it’s nowhere near on a par with men. It barely breaks into the double digits.

This is all from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s recent research on the percentage of patents granted to women or to teams that include a woman.

I recently interviewed Amanda Myers, acting deputy chief economist at the USPTO, about that research. The results provide an important indicator of women’s participation in science and technology. USPTO last compiled the numbers in 1999. The current report concentrates on 2007-2016, but includes data going back to 1976.

I joked that Myers herself had chosen to join the field known as the dismal science: Economics. She chuckled and said that economics seemed to best combine two of her keen interests, mathematics and history.

That’s what self realization is all about, the freedom and opportunity to pursue that which interests you, however far your talents will take you.

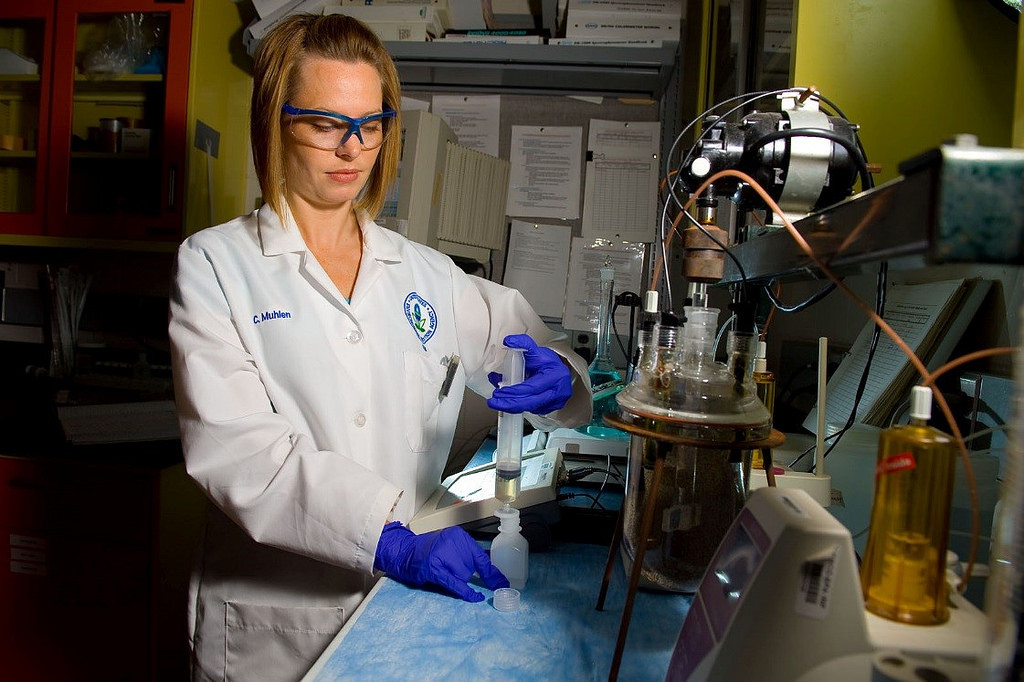

Having just interviewed a trio of prize-winning female federal STEM employees, I was interested to see what USPTO found. The study quantified what we probably already knew. Twenty-one percent of patents in 2016 went to teams that included at least one woman. The percentage of women that are inventors stood at 12 percent. USPTO calls that percentage the “women inventor rate.” That’s better than 7 percent rate in 1980. But over the decades, individual women or all-women teams have received a mere 4 percent of patents.

Women most often receive patents in the fields of chemistry and design. They do worst in mechanical and electrical engineering, and this phenomenon has stood consistently since the 1970s.

Particularly interesting were USPTO’s state-by-state findings. Delaware, where many chemical and pharmaceutical companies are headquartered, has the highest women inventor rate at about 20 percent. The District is second, which Myers speculated was because the federal government tends to foster female science participation at higher rates than industry.

Michigan, a fountain of automotive patents, was way down near the bottom on the women inventor rate scale. That seems to correlate with the electrical and mechanical engineering findings. Cars today are clusters of computers wrapped in steel, glass and plastic.

If you’re wondering who specifically harbors the highest women inventor rates, it’s Proctor & Gamble at nearly 30 percent. The company with the most women inventors working there was IBM. The assignees in that top list make everything from pancreas pills to front-end loaders.

Myers acknowledged the report raises more questions than it answers. The fundamental question remains a mystery: Why women aren’t involved more in science and technology? Likely it’s a combination of factors but to the extent it can, USPTO will release its data sets for those who want to do more research.

Thankfully the report’s authors refrain from preaching. But they’ve provided a valuable piece of insight into a puzzle that should concern anyone who supports American leadership in the science and technology.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Tom Temin is host of the Federal Drive and has been providing insight on federal technology and management issues for more than 30 years.

Follow @tteminWFED