Updated: Industry group asks Senate Appropriations Committee to rein-in FFRDCs

The Professional Services Council, an industry association, asked the Senate Appropriations Committee to limit the type of work Federally-Funded Research and De...

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to reflect the fact that Noblis is not connected to MITRE or FFRDCs. A Noblis spokesman provided a statement from Noblis CEO Amr ElSawy, “Noblis strictly adheres to all government regulations regarding conflicts of interest and has implemented a systematic process to identify and avoid all OCIs in the work we do. Our objectivity is the key to Noblis value to our clients and is the basis of the excellent reputation for ethics and integrity that we have worked hard to build and have earned with our clients.”

Updated July 5, 415 p.m., this story now includes clarifications from MITRE.

The House version of the fiscal 2020 defense authorization bill tells the Defense Department to work with federal funded research and development centers (FFRDCs) for 11 different projects.

These range from a study of the barriers to entry into the Armed Forces for English learners to an independent assessment of the force structure and roles and responsibilities of special operations forces, to a study on how to improve the competitive hiring at DoD.

Over the last half century, FFRDCs have played an important role in helping agencies address some of the biggest challenges. In 2015, the latest data available, 12 agencies awarded 42 FFRDCs more than $11 billion in research and development funding, which accounted for almost 9% of all R&D funding across the government.

FFRDCs are so attractive to agencies for several reasons including the fact that the government establishes and approves these organizations, provide capabilities that do not exist elsewhere and are expected to be independent advice to agencies. These organizations also are supposed to provide advice and studies, but not bid on services to implement their findings.

Over the last decade, the line between FFRDC and service provider has blurred too often, leaving some concerned that these organizations have an unfair advantage to bid on work they have.

The Professional Services Council (PSC), an industry association, raised these concerns to Senate Appropriations Defense Subcommittee lawmakers in a letter last month.

“DoD benefits from FFRDC efforts in basic research for which there is insufficient return available to support private sector investment. DoD also benefits from certain ‘trusted agent’ support from FFRDCs. These are among the legitimate functions for which FFRDCs were established,” PSC writes in the letter obtained by Federal News Network. “However, too often, these same FFRDCs are being awarded sole-source, non-competitive contracts by DoD to perform work that private sector, for-profit U.S. companies can do equally well or better, while saving scarce funds through full and open competition. This violates the intent of the Competition in Contracting Act (CICA) and undermines the real and valid purposes for which FFRDCs exist.”

At the same time, other experts say FFRDCs are restricted from bidding on resulting work from their research, but can serve as a technical resource to the government and to contractors during the implementation phase.

Conflict of interest concerns raised

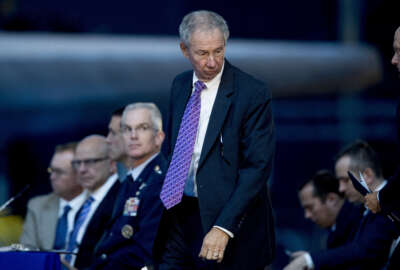

David Berteau, the president of PSC, said in an interview that the appropriations committee increased DoD funding by 3% in 2019 for research and development, but didn’t give the department or the FFRDCs any additional employees but that is not the case for 2020. Berteau said the House defense appropriations bill included an increase in the number of employees that FFRDCs hire and he said that could exacerbate the current situation of conflicts of interest lines being blurred.

“The immediate issue we see is with return of threat from China and other nations and the emphasis on innovation across DoD from Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering Michael Griffin, DoD needs technical expertise to address those investments in innovation,” Berteau said. “We believe there is that capacity in the FFRDCs if they stop doing the other things that they weren’t meant to do.”

John Weiler, the CEO of the IT Acquisition Advisory Council, said MITRE is the biggest culprit in this blurring of lines, pointing several instances where the FFRDC provided research and then bid on the services to implement the research creating a conflict of interest.

MITRE operates FFRDCS in areas such as homeland security systems, national cybersecurity and national security engineering.

Weiler claimed there are several examples of MITRE double dipping to do the research and then winning the technical production contract that creates a conflict of interest.

Weiler said the Army, Air Force and Navy’s distributed common ground system is one of those where MITRE supported both the systems engineering effort as well as the oversight by the service’s acquisition shops.

“Congress directed the Army to review commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) data analytics and cloud offerings in wake of failed DCGS-A, and the Program Executive Office, Intelligence, Electronic Warfare and Sensors (PEO IEW&S), whom also hired MITRE,” Weiler said. “MITRE did a study which concluded that no commercial products could meet the need again, which followed a similar study years ago leading to the failed Army Red Disk program. Palantir filed suit in federal court and proved there were commercial products.”

Weiler also said there are other examples of conflicts of interest where MITRE’s seemed to have played both sides of the effort—the Defense Information Systems Agency’s security mobility program and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services healthcare.gov development.

A MITRE spokeswoman said in an email to Federal News Network, “As the nation faces an ever increasing set of national security challenges, we thought it would be good context to explain that the work we are assigned to do for the DoD is the result of a strong governance process run by the DoD to focus MITRE on a unique set of national security challenges facing this country. This DoD process has been independently reviewed by the Government Accountability Office in the past with favorable results.”

The spokeswoman added that MITRE’s efforts are closely aligned with Griffin’s priorities.

“We constantly strive to ensure our work programs are consistent with the Federal Acquisition Regulations and the mission, purpose and scope of the specific FFRDC,” she said. “The taxpayers and those defending this country deserve nothing less.”

FFRDCs need to stay in their lanes

Berteau said PSC, which didn’t mention MITRE directly, fully understands the value FFRDC’s bring to the table.

“They matter a lot particularly around their ability to do science and technology research that is not dictated by always getting a return on investment. It is critical to have a trusted agent side-by-side with the government as it develops requirements,” he said. “It’s about FFRDCs stop doing things they shouldn’t be doing to free up resource so they can tackle the nation’s science and technology challenges to stay ahead of other nation states.”

PSC told the committee that FFRDCS are encroaching into technical work and other functions that should be open only to for-profit companies.

“This encroachment into legitimate private sector business opportunities by government-protected non-profits hurts small businesses by prohibiting them from even competing,” the letter states. “In addition, the cost of FFRDC personnel is much higher. While this might make sense when providing unique talent to DoD, it does not make sense when other companies can do the work with the same proficiency at much lower costs.”

PSC said Congress has taken steps in the past to constrain FFRDC’s alleged encroachment.

“Most recently, section 8024 of the fiscal 2019 Department of Defense appropriations conference report included language to prohibit FFRDCs from certain activities and unauthorized growth,” the letter states. “PSC respectfully requests that these provisions remain in the 2020 Defense appropriations act and that those provisions be coupled with reductions in staff years of technical effort (STEs) from the levels in 2019’s Section 8024(d) and with decreases in appropriations from the levels in Section 8024(f) back to 2018 levels.”

Additionally, PSC asked lawmakers to direct DoD to report to the committees on the “proper roles of FFRDCs in providing essential, unique support to DoD, particularly as they have expanded their engagement well beyond the core missions they were created to perform.”

The Senate defense 2020 appropriations bill is not yet out of committee. The House’s version, which passed the out of the appropriations committee in May, has two FFRDC provisions. One would “prohibits the use of funds appropriated in this Act to establish a new federally funded research and development center (FFRDC), pay compensation to certain individuals associated with an FFRDC, construct certain new buildings not located on military installations, or increase the number of staff years for defense FFRDCs beyond a specified amount.”

The other provision would prohibit funding “to establish a new Department of Defense FFRDC, either as a new entity, or as a separate entity administrated by an organization managing another FFRDC, or as a nonprofit membership corporation consisting of a consortium of other FFRDCs and other nonprofit entities.”

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED