CMS sees improper payments drop after ‘targeted review’ of requirements

One of the biggest culprits of improper payments in the federal government — the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services — is making progress to combat the...

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

One of the biggest culprits of improper payments in the federal government — the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services — is making progress to combat the issue.

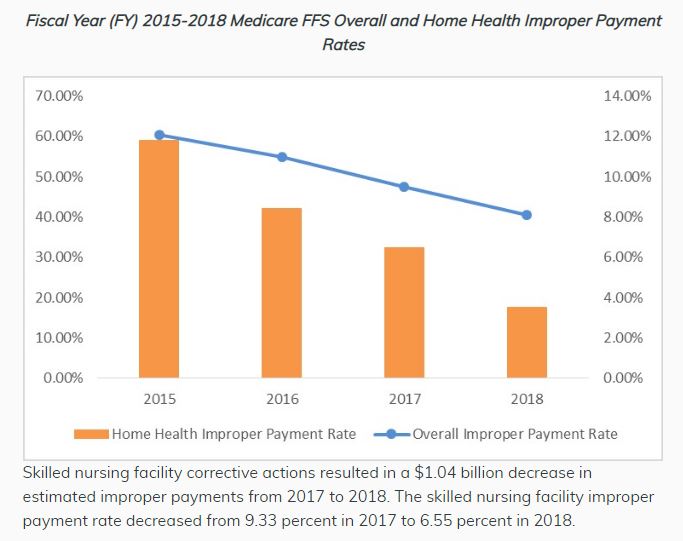

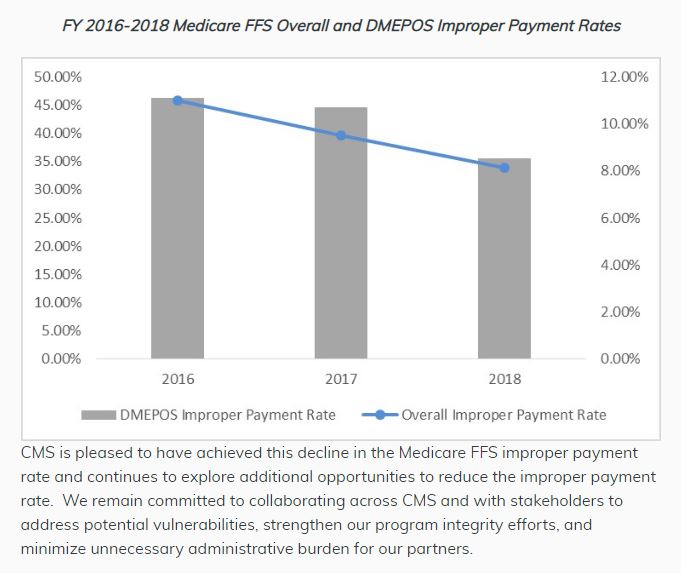

The agency recently announced that its Medicare Fee-for-Service improper payment rate is now at its lowest since 2010. The rate dropped from 9.51 percent in 2017 to 8.12 percent in 2018, representing a $4.59 billion decrease in estimated improper payments.

In addition, CMS reported improper payment rate reductions across the board for Medicare, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, or CHIP, for the first time in history.

“Our accomplishments over the past year were the result of a focused effort to target root causes of improper payments,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a blog post Friday. “CMS also implemented a targeted review strategy that focused on provider education, assistance and burden reduction. The agency’s actions emphasized prevention-oriented activities.”

“Our accomplishments over the past year were the result of a focused effort to target root causes of improper payments,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a blog post Friday. “CMS also implemented a targeted review strategy that focused on provider education, assistance and burden reduction. The agency’s actions emphasized prevention-oriented activities.”

Improper payments are a longstanding problem across the federal government, including their definition and understanding. As Verma stated in her post, improper payments are not always fraudulent but are payments that do not “meet statutory, regulatory, administrative or other legally applicable requirements.” They could be overpayments or underpayments, a point echoed by several CFOs at a September industry training session in Washington, D.C.

Nevertheless, improper payments and overall inadequate fiscal oversight have kept the Medicare and Medicaid programs on the Government Accountability Office’s High Risk list since 1990 and 2003, respectively. In fiscal 2017, Medicaid alone accounted for an estimated 26 percent of governmentwide improper payments, GAO reported.

In CMS’ notice, Verma said the decreases in improper payments were due to a “targeted review strategy” with an emphasis on provider education, assistance and burden reduction, along with prevention-oriented activities, including simplifying and clarifying policies.

Those policies include:

- Proof of delivery requirements.

- Signature requirements.

- Medical review of inpatient rehabilitation facility claims.

- Milling for immunosuppressive drugs.

- Allowing teaching physicians to verify student’s evaluation and management visit notes.

Going forward, CMS said it is considering a couple of private-sector innovations to reduce improper payments and the burden on Medicare and Medicaid providers. Among these are expanded use of prior authorization by the Center for Program Integrity. The center also plans to make documentation requirements visible to clinicians through their electronic health record, CMS said.

Root causes vary

It can be difficult to pin down exactly why improper payments occur, but according to a report from the Partnership for Public Service and Deloitte, issued Nov. 13, insufficient documentation was the cause 28.5 percent of the time governmentwide in FY 2017. Inability to authenticate eligibility accounted for 23.5 percent of improper payments, while administrative or process errors made at the state or local level accounted for 17.8 percent of improper payments.

Dave Mader, one of the report’s contributors and a former controller at the Office of Management and Budget, said dealing with different state-level programs makes staying on top of improper payments for CMS more difficult than a federal program that delivers payments directly to recipients. Medicaid, for example, has to include errors at the state or local level in their federal improper payment rate, which accounts for about 59 percent, the report found.

But Mader said CMS had done “an excellent job” of reaching out to the states on this front, citing the agency’s Medicaid Integrity Institute training program run in conjunction with the Justice Department.

While at OMB from 2014 to 2017, Mader also oversaw new requirements for agencies to identify root causes of improper payments.

“They have now I think in many, many agencies been able to identify in a particular program what exactly is driving the improper payment rates, whether it’s an actual loss to the government or it was an improper completion of a form where the individual was indeed entitled to the payment in the amount that was provided,” he said.

The nature of CMS payments can also make them susceptible to error, according to Linda Miller, a director in Grant Thornton’s Public Sector Fraud Risk Assessment practice.

Miller, a former assistant director of GAO’s Forensic Audits and Investigative Service, said several unpredictable variables can lead to improper payments.

“Really the only way to know that a doctor is overbilling, a provider is overbilling, is to be able to go and find out whether the patient’s medical history supports whatever the bill in question is for,” she said.

She also said patients may not understand insurance companies’ full explanations of benefits or the codes used by doctors in their billing. Therefore detecting Medicare fraud requires significant due diligence, Miller said.

Tracking helps but more prevention needed

Over the last decade Congress has taken several measures to combat improper payments legislatively, including with the Improper Payments Elimination and Recovery Improvement Act of 2012 and the Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015.

But Miller said the focus on estimating and reporting improper payments has overshadowed prevention efforts at federal agencies. That’s where data analytics can play a larger role, provided agencies can overcome cumbersome data-sharing agreement requirements and past hesitations about information privacy to share information, she said.

“One opportunity that is being missed, I think, across government right now is the use of analytics to identify trends and patterns that indicate suspicious activity and then being able to take action on those trends,” she said. “[The Center for Program Integrity] has a data analytics group that’s the most advanced in government and I would guess, though I don’t know for sure because there’s a lot of variables in how CMS has been able to drop their improper payments rate, but I would guess a lot of it has to do with the sophistication of CMS’ analytics capabilities when it comes to identifying provider irregularities.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Amelia Brust is a digital editor at Federal News Network.

Follow @abrustWFED

Related Stories