A new survey from the Association of Federal Enterprise Risk Management (AFERM) shows more than 50% of the respondents say their ERM programs are either “highly...

The good news is agencies are getting better at managing their enterprise risks. In the four years since the Office of Management and Budget added this concept to Circular A-123, nearly every agency is gaining maturity and experiencing the impact of this approach.

But the old adage “culture eats strategy for lunch” is, once again, popping up its ugly head up.

David Fisher, the former chief risk officer of the IRS who now leads the risk consulting practice at Guidehouse, said embracing enterprise risk management (ERM) concepts continues to stand out as the key piece to getting better outcomes.

“We are sort of getting to that mid-point score now on the culture piece of things, which has improved over the years, but it still has quite a ways to go,” Fisher said in an interview with Federal News Network. “We may be spending unnecessary resources to mitigate risks that are perceived to be pretty low. We could be spending more on human capital, programmatic or cyber risks. The data is telling us to realign those resources a little bit.”

The progress in moving the federal culture to view ERM in a new way is among the overarching takeaways from the latest survey from the Association of Federal Enterprise Risk Management (AFERM). The sixth annual survey, which Guidehouse sponsored, received responses from 37 agencies, including 15 cabinet level departments, representing the broadest response base ever.

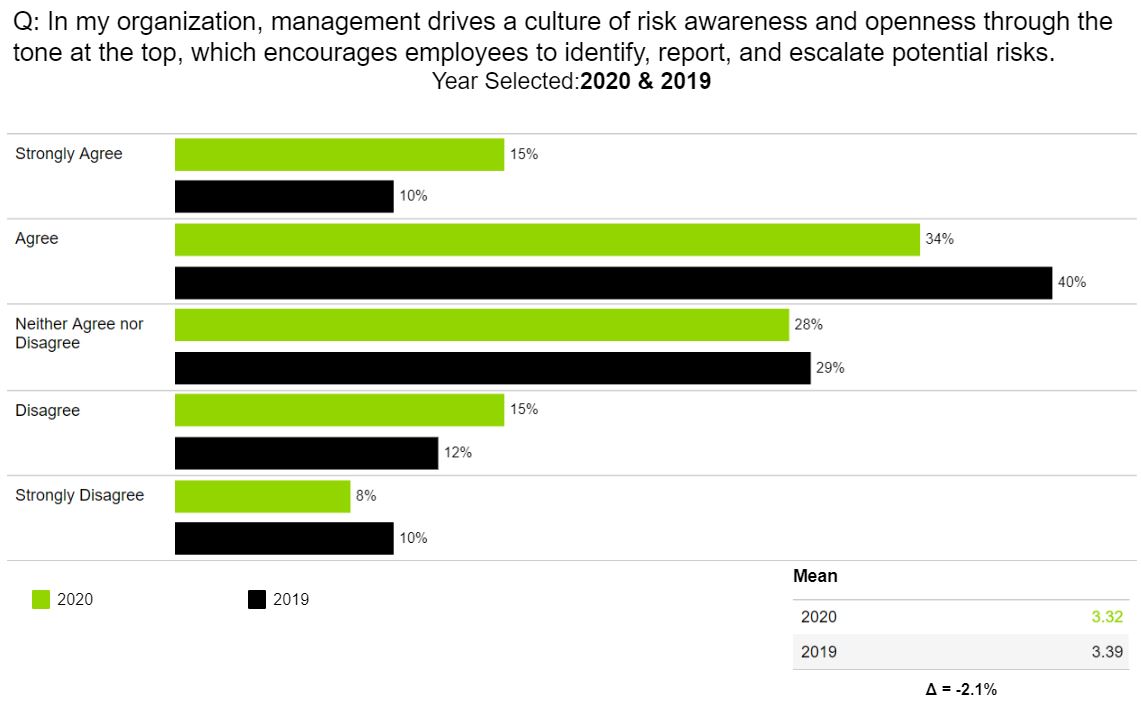

“The survey portrays culture and leadership-related challenges as being the most prominent barriers facing organizations attempting to establish and maintain a formal ERM program,” the survey states.

Nicole Puri, the president-elect of AFERM and the chief risk officer at the Bureau of the Fiscal Service in the Treasury Department, said while there were no major surprises in the survey, the one thing that stood out to her was related to culture.

“One of the barriers to success of ERM remains the difference between actual risk tolerance and public risk tolerance,” she said. “What I mean by that is what an agency is actually willing to do internally, meaning the types of decisions that they make about how they use their resources and where they don’t use their resources, and what they are willing to say publicly about it are often different. That comes into play when you are thinking about things like compliance activities. If an agency is prioritizing compliance or not getting inspector general findings over spending money on activities that can actually impact their mission. That illustrates one of the points of the survey that there is a mismatch of where resources are deployed and where perception of the biggest risks are. Compliance continues to win that battle often.”

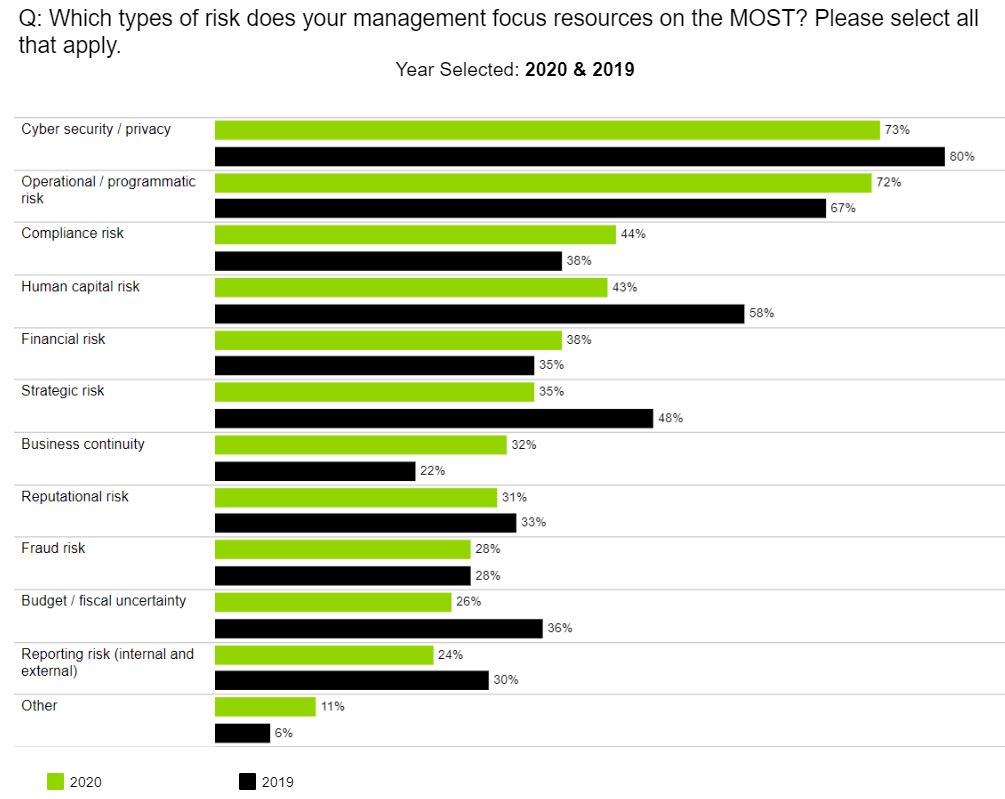

AFERM drives home that point in the survey by asking what are the biggest risks to the agency versus which ones do they spend more time worrying about.

Fisher said respondents reported for the third year in a row that cyber risk is their biggest concern. But they also pointed to compliance areas like fraud, reporting and financial risk were also getting a lot of focus despite it being perceived as a small exposure to the agency.

“We’ve seen this result for a couple of years in a row. If you are getting audited on these risks, you will spend a lot of time on them,” he said. “I spoke with the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency (CIGIE) about the results of our survey and this may be one of the things the IGs also need to take a look at as well. Maybe we should be doing some of the audits in these other areas that are maybe high risk instead of the ones we’ve done year after year.”

Puri said part of the reason for the misaligned focus at some agencies is it’s not uncommon for the ERM function to be aligned with the internal control efforts of an agency.

“What that has done is, I think, continued that focus that ERM is related to internal controls and we should practice them together, which therefore continues that compliance focus that we see,” she said. “It continues to be a factor in how we are able to move forward and mature ERM in the federal government when you still have that tie back to internal controls or more of a compliance function in general.”

Puri said tying ERM and internal controls together at first may be fine for agencies just getting started, but as they mature, the focus has to be on all the risks, not just ones that are considered compliance based.

“You need to start looking at what should you be spending money on or where are the risks coming from if they are not compliance risks?” she said. “If you want to get value out of ERM, you have to take a more strategic look.”

Puri said research in the ERM space will show 60% to 80% of all risk is strategic and 20% is financial or operational.

“You have to think about those strategic risks and trying to identify ways to mitigate those and picking the right ones, and spending less time on those that make up a smaller percentage of your overall risk portfolio,” she said. “That gets harder when you are linking that program to something that is only about financial risk and not about operational risk.”

Fisher added the survey data demonstrates the benefits of moving ERM into A-123 to create and establish an agencywide program.

But as agencies have matured, some have kept ERM in the CFO’s office and continued to focus on financial and reporting risks.

“They have had difficulty penetrating the mission side of the organization,” Fisher said. “In fact, we’ve seen some agencies who have stood up two ERM programs. One focused on compliance in the CFO areas and one focused on the mission side. Sometimes they talk together and sometimes they don’t. Some organizations are struggling with exactly how do these things fit together, so how do we make sure that while A-123 was a great motivator to get interested in ERM, how do we not just align it with traditional A-123 activities related to internal controls and go beyond that to focus on some of these mission and strategic type of things.”

In many ways, this goes back to the idea of culture. Puri said agencies that have established an ERM office led by a dedicated, experienced chief risk officer are more likely to be successful.

“It really does have an impact if you don’t have the right level of dedication. It’s going to be harder for executives at agency to see why this is important if it continues to run at a lower level. Pulling it up into the executive ranks really can have a great impact,” she said.

Fisher said AFERM and other experts believe some sort of governmentwide guidance would be helpful, whether it’s a new ERM circular or legislation or something else, to continue to push these concepts forward.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED