CFOs, OMB say one solution to improper payments is less ‘misleading’ definition

Cutting down on improper payments is on the list of cross-agency priority goals in the President's Management Agenda.

Stopping improper payments from federal agencies is No.9 on the President’s Management Agenda’s list of cross-agency priority goals.

But some say part of the problem lies in the definition of improper payments and public misperception of the issue.

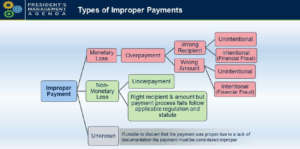

As it stands, the Improper Payments Information Act of 2002 defines improper payments as those which “should not have been made or that was made in an incorrect amount … under statutory, contractual, administrative, or other legally applicable requirements; and includes any payment to an ineligible recipient, any payment for an ineligible service, any duplicate payment, payments for services not received, and any payment that does not account for credit for applicable discounts.”

Carole Banks, deputy chief financial officer at the Treasury Department, called the term “improper payment” in itself misleading while partaking in a panel of CFOs at the Association of Government Accountants’ Internal Control & Fraud Prevention Training event Friday in Washington, D.C.

“It implies that there is something in every case erroneously happening on the part of the agency to make a wrong payment, leading to blunders or errors by the agency. And that’s how it’s being characterized in the public,” she said. “In reality though, there are a lot of improper payments that are being made, or payment errors that are occurring, not related to fraud and not because of some processing or administrative error caused by the agency.”

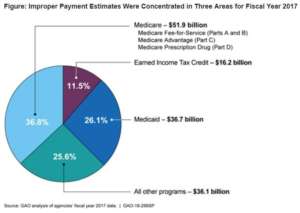

An improper payments work group of 19 of the most susceptible agencies was started in the fall. Banks said the Earned Income Tax Credit program and Department of Health and Human rank at the highest of that list, and therefore Treasury and HHS are co-leading the initiative.

Banks said the group conducted a survey of agencies and 40 percent of aggregated monetary loss by improper payments was due to statutory or regulatory limitations beyond an agency’s control that can cause payments to be misdirected — the primary root cause.

She also said the amount of cash loss is misunderstood because of improper documentation. She called this an internal control deficiency but said it still did not mean the payment was incorrect.

“So is that really and should that be really counted for as a cash loss? Did we really lose that money? The answer to that is ‘no,’” she said. “And unfortunately, the public is picking up the wrong information, the wrong amounts.”

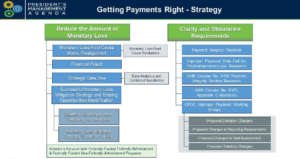

Now agencies will report two amounts, Banks said: a nonmonetary number encompassing cash and non cash-related improper payments, and the pure cash loss. She also said they public needs to be able to understand what is truly within and outside of agencies’ control, and it’s something she said agencies can change “now.”

“It’s what the public needs to see,” she said. “If they’re going to publish, they need to have the right information — they need to have the right amounts.”

Heather Pajak, a senior policy analyst at the Office of Management and Budget, said on a separate panel during the AGA training that CAP Goal 9 is primarily focused on fixing improper payments that result in monetary losses. But historically, the federal government has looked at improper payments in a broad sense.

She described three “buckets” in which to organize improper payments, the first two being monetary and nonmonetary, as Banks said, and the third being unknown. Unknown improper payments were those which lacked proper documentation.

Pajak said that when it comes to reducing monetary loss from improper payments, agencies are implementing data analytics, leveraging centers of excellence among themselves and at the state level to develop new mitigation strategies. But clarification of existing statues is also crucial, she said.

Two pieces of proposed legislation to combat the problem have been introduced but not taken up by committees: The Payment Integrity Information Act of 2018, and the Stopping Improper Payments of Deceased People Act.

The first bill would set in statute OMB’s current policy for agencies to conduct risk assessments and requires OMB to report a governmentwide improper payment estimate. The second bill would amend the Social Security Act to allow federal and state agencies to access the Social Security Administration’s complete death information, according to documents provided by AGA.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Amelia Brust is a digital editor at Federal News Network.

Follow @abrustWFED