Another look at the different worlds of federal workers

In locations with fewer federal workers and/or fewer high grade jobs, promotion opportunities for employees in lower grade jobs are more limited than that of...

This column was originally published on Jeff Neal’s blog, ChiefHRO.com, and was republished here with permission from the author.

My most recent post addressed the differences between being a fed in the D.C. area versus the rest of the United States. Having lived and worked for many years in Florida, Tennessee and Ohio before moving to the National Capital Region (NCR), I observed biases against and in favor of both field and headquarters feds. One commenter reminded me that there are other groups of federal workers that cannot be easily described with the field and headquarters labels and that my last post was silent on that. It is a valid point, so I decided to take a look at other ways groups of federal employees might be different from one another, this time focusing on grade level.

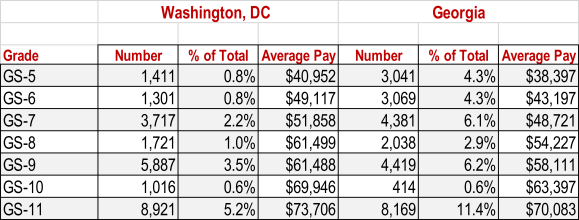

As I said last week, one of the most striking differences is grade level and the pay that comes with it. Last week I focused on high grades. This week I’m looking at lower to mid grades. If we compare D.C. to a state (e.g., Georgia) that is about average on grade distribution, we see that there are tiny numbers of lower grade employees in D.C., with just over 6,400 employees (3.8 percent) in grades 5, 6 and 7. In Georgia, 10,491 employees (14.7 percent) are at GS-5, 6 and 7. Those numbers are important. In D.C., the median home or condo price is more than twice that of Atlanta, which itself is more than twice that of Georgia as a whole. Rent prices are also about one-third higher in D.C. than in Atlanta. The cost of living in D.C. is among the highest in the country, but those often-forgotten GS-5 employees have to pay to live here. Whatever benefits may come from living in a city such as D.C. (and there are many), lower-graded federal workers in the NCR and other high cost areas often struggle to pay rent or are forced to live farther away and commute long distances to work. It is surprising to see how many feds in the NCR commute as many as two to three hours each way. Imagine spending six hours a day in your car, just so you can have an affordable place to stay.

The situation is a bit different in Georgia and other states that are not known for high costs. Pay for a GS-9 comes in at about the same as the median income for the state. Even though there are far larger numbers of lower and mid-grade employees in those locations, they are able to have a much better standard of living.

There is more to grade level that just pay, even though pay makes a huge difference. In locations with fewer federal workers and/or fewer high grade jobs, promotion opportunities for employees in lower grade jobs are more limited than that of employees at the same grade in the NCR. Some employees in lower graded jobs are just passing through those grades (entry level hires for higher graded jobs).

For the folks who do not have that ticket, such as people in clerical jobs, the opportunity to advance is related to how well they do their jobs, education and training, turnover in higher grade jobs, and often plain old luck. In researching this post, I found some striking numbers. For example, clerical jobs generally do not require formal education beyond high school, yet 21 percent of federal clerical employees nationwide have a bachelor’s degree or higher. Four percent have a master’s degree or higher. The numbers are the same in Georgia, but are a bit lower in D.C., where 17.3 percent have a bachelor’s degree or higher. The degree or lack of it does not mean those workers are any less important or any less bright, but it may mean promotion opportunities are more limited for those without degrees. It also means there are a lot of people in government who have education that will qualify them for jobs in career fields where there are excellent opportunities to advance. A degree is not always required for higher grade jobs, but half of GS-11s in Georgia have a bachelor’s degree or higher, and 80.4 percent of GS-13s have a bachelor’s or higher. In D.C., 65.7 percent of GS-13s have a bachelor’s degree or higher. The disparity between D.C. and the rest of the country is most likely because of the demand in the NCR. There are so many federal jobs and so many vacancies that employees without a degree have a better chance of getting ahead.

The differences in grade levels may have some other, less visible, effects. Employees at higher grades are typically privy to more information about what is going on in an agency. They are more likely to be in the meetings where decisions are discussed and made, and because of the nature of their work, more information flows their way. Access to information can be an important aspect of moving up. It also appears that employees in higher grades make their views known more often. Let’s use the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey as an example. The response rates for employees in GS grades 1–6 is 31.8 percent. It increases to 45.0 percent for those in GS grades 7–12, and goes all the way up to 58.5 percent for GS grades 13–15. The response rate for employees in other pay plans —the largest of which is the Federal Wage System — comes in at 38.3 percent. Response rates to the FEVS also differ by education level, with employees with a high school diploma or less responding at a 37.6 percent rate, those with some college responding at 38.9 percent, and those with a bachelor’s degree coming in at 49.5 percent. Employees with more than a bachelor’s degree have a 52.6 percent response rate.

One other interesting data point on the field vs. headquarters divide with respect to the FEVS is the response rates. In the 2017 FEVS, headquarters employees had a response rate of 42.5 percent, while field employees came in at 57.6 percent. The much higher response rate in the field may indicate a lot of things, one of which is that those folks are hungry for their voices to be heard. Note that “headquarters” means more than the NCR. There are lots of people who are called “headquarters” who would not think of themselves as being in a headquarters organization. I will go into more detail on that in a future post.

All of that may mean that the views of employees in lower grade positions and in the field may not be heard to the same degree as the higher graded employees and those in headquarters. That may mean that agency programs that are intended to improve morale and engagement miss the concerns of large groups of people.

However, we look at it, the federal workforce comprises a wide variety of people in virtually every part of the U.S., with varying levels of education, pay, access to information, and involvement in decision-making. Trying to lump them into one big group does not work, even when that group is an individual agency. That means a new pay system that meets the needs of high grade employees may be terrible for lower graded employees, and vice versa. A solution that works for engineers may not work for contract specialists, and solutions that work in the NCR may not work in Albany, Georgia. When we attempt to solve problems in government, including civil service reform, we must be willing to walk away from one-size-fits-all and align the talent management processes and systems with the talent we are trying to hire, develop and retain.

Jeff Neal is a senior vice president for ICF and founder of the blog, ChiefHRO.com. Before coming to ICF, Neal was the chief human capital officer at the Homeland Security Department and the chief human resources officer at the Defense Logistics Agency.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.