OMB released the final vulnerability disclosure policy (VDP) and DHS published the related binding operational directive and implementation guidance so agencies can...

The Office of Management and Budget and the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency dropped a trifecta of guidance today that will keep chief information security officers busy for the next year.

OMB released the final vulnerability disclosure policy detailing the overarching approach agencies should take to address new and long-standing cyber vulnerabilities.

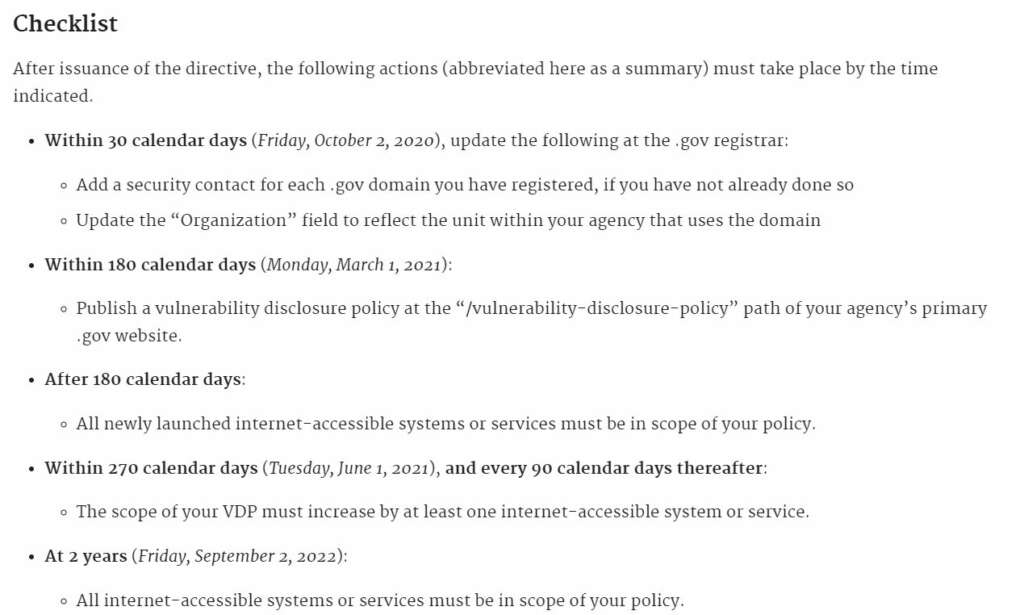

At the same time, CISA published the VDP binding operational directive and implementation guidance giving CISOs a series of deadlines and questions to consider as they are setting up their VDP and bug bounty programs.

“Federal agencies are currently incorporating two types of coordinated vulnerability disclosure (CVD) programs into their security efforts: Vulnerability disclosure policies (VDPs) and bug bounties,” said Russ Vought, OMB director, in the memo to agency leaders. “VDPs establish processes for the identification, management, and remediation of security vulnerabilities uncovered by security researchers. They are among the most effective methods for obtaining new insights regarding security vulnerability information and provide high return on investment. They also provide protection for those who uncover these vulnerabilities by differentiating between good-faith security research and unacceptable means of gathering security information.”

Bug bounties, meanwhile, are different than VDPs because they offer compensation based on established parameters to security researchers who report the vulnerabilities they find.

“While several organizations in the federal government have used bug bounty programs effectively, each agency should carefully weigh the cost, organizational competence and maturity required for a strong and sustainable program,” Vought wrote.

The VDP and bug bounty initiatives grew out of several successful efforts across the Defense Department, the Census Bureau and other agencies as a way to find and mitigate vulnerabilities using a group of trusted “white-hat” hackers.

“VDPs are a good security practice and have quickly become industry-standard. Even in government, others have harnessed the benefits of working with security researchers before,” said Bryan Ware, the assistant director for cybersecurity at CISA, wrote in a blog post. “More recently, we released guidance to election administrators for setting up their own VDPs (something that community is starting to do). At CISA, we believe that better security of government computer systems can only be realized when the people are given the opportunity to help.”

The policy, BOD and implementation guidance are the first steps for agencies to take advantage of these tools in a standardized way. DoD kicked off the first bug bounty effort in government in 2016 and the approach and use of these tools have been ad hoc over the last almost five years.

Starting with the policy, OMB said a VDP should address five areas, including a clear reporting mechanism, timely feedback and ensuring system owners know about problems found within 48 hours.

CISA build on that part of the policy in the BOD and implementation guidance.

In the directive, CISA directs agencies to issue a VDP policy by March 1, within 180 days, that addresses nine items, including the specific systems that are in scope, the types of testing allowed and where the report should be sent.

The implementation guidance breaks down the policy further.

“Though there are common themes in different organization’s vulnerability disclosure policies, there is no one-size-fits-all approach. The required actions in this directive are merely the mandated elements of your policy; they are the minimums required, not the ceiling,” the document states.

CISA says a policy ought to:

“Your policy should be written in plain language, not legalese. It need not be long. The tone should be inviting, not threatening,” CISA stated.

The implementation guide and the BOD also offers insight into other pieces to the VDP, like how to develop data and incident handling procedures, the need for agencies to let individual bureaus have their own VDP program and the use of contractor or third-party services.

CISA also plans to launch a VDP-as-a-service next spring under its Quality Service Management Office (QSMO). GSA released a solicitation in early August for a vendor to provide the platform and services.

OMB and CISA released draft versions of the policy and BOD in November and asked for agency and industry feedback. CISA said it received more than 200 recommendations from 40 different people or organizations.

Ware wrote that the comments asked about whether mobile applications would be part of the VDP—which they are now. Several comments asked about target timelines to fix vulnerabilities.

“Fixing a vulnerability is not always push-button, and requiring deadlines might create perverse incentives where a lower severity-but-older vulnerability takes organizational precedence over newer-but-more-critical bugs. Deadlines might also cause rushed fixes,” Ware wrote. “The final directive makes clear that the goal of setting target timelines in vulnerability disclosure handling procedures is to help organizations set and track performance metrics; they are not mandatory remediation dates.”

For the bug bounty program, OMB kept it much simpler, telling agencies to use these tools as they see fit, and requiring the General Services Administration, the Commerce Department and OMB to decide if there is a need for a centralized capability.

In the BOD, CISA also addresses bug bounty programs in a small way, telling agencies that they can serve as motivators to get a wide range of people participating.

“You may choose to add financial incentives to the discovery of certain issues or on specific systems,” the BOD states. “Even if you don’t choose to offer rewards — and healthy competition between agencies on the coolest vulnerability reporting swag would be a wonderful outcome of this directive — you may elect to include language in your VDP that makes clear your reward stance, which facilitates shared expectations from the start.”

Once agencies have the VDP platform in place, CISA expects them to update it after 270 days initially and then every 90 days thereafter and add at least one more system to the review process.

“This directive is different from others we’ve issued, which have tended to be more technical — technological — in nature. At its core, BOD 20-01 is about people and how they work together,” Ware wrote. “That might seem like odd fodder for a cybersecurity directive, but it’s not. Cybersecurity is really more about people than it is about computers, and understanding the human element is key to defending today and securing tomorrow.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED