Grassley: DoD audit plan ‘doomed to failure’

Amendment set for Senate debate this week would focus DoD's attention on fixing weaknesses in "feeder systems" that supply vital financial data.

At least since the passage of the 1990 CFO Act, Congress has been hounding the Defense Department and every other federal agency to get their books into a condition that can be scrutinized by outside auditors.

But now that it’s finally come time for DoD —the lone holdout — to actually conduct the first full-scope audit in its history, at least one senator thinks it would be a terrible idea for the department to follow though with that plan, because the Pentagon simply isn’t ready.

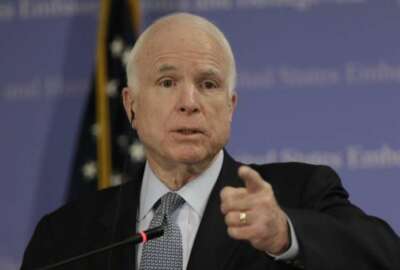

Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) has long been a critic of the department’s failure to achieve audit readiness, but also believes that trying to force one through now would be a monumental waste of time and money, since literally no one expects the department to earn a clean opinion on the audit that’s scheduled to get underway next fiscal year.

The costs, he told colleagues on the Senate floor Tuesday, far outweigh the benefits.

“These audits, which are touted as the largest ever undertaken, could top $200 million,” he said. “Spending so much money on audits that are doomed to failure would be a gross waste of tax dollars.”

That doesn’t mean the department should fold its tents and give up on auditability, Grassley said, only that it should focus its resources on fixing the financial management weaknesses that make a clean audit so difficult – namely, the “feeder systems” that DoD’s more modern enterprise resource planning systems rely on for their data about financial transactions, some of which have been in operation since the 1960s.

“Fix them, and then the rest should be just a piece of cake,” Grassley said.

An amendment scheduled for consideration during this week’s Senate debate on the annual Defense authorization bill would zero-in on the feeder systems and appears intended to drive toward a more thorough consideration of the costs and benefits involved in requiring the department to undergo an audit before it can pass one.

The language, co-sponsored by Grassley, Ron Johnson (R-Wisc.), Joni Ernst (R-Iowa) and Ron Paul (R-Kenn.) requires DoD to report to Congress on what it’s done to test and verify the accuracy of the data in those legacy systems, proffer projected dates on which each element of the department will earn a clean audit opinion, and submit regular reports on much money DoD is spending in its pursuit of audited financial statements under its current approach.

The Defense Department doesn’t disagree with Grassley’s contention that feeder systems are a massive and persistent obstacle to clean audit opinions.

In the most recent update to its financial improvement and audit readiness plan, issued in May, the DoD comptroller’s office said it was “nearly impossible to ensure data are completely and accurately feeding” between those systems, which still lack the basic capabilities needed to undergo a successful audit and, in many cases, require manual workarounds to satisfy audit demands.

But it’s been DoD’s longstanding opinion that the best way to uncover and fix those weaknesses is to put the department’s entire financial management infrastructure through its paces under the eye of independent auditors.

That view was reaffirmed by the current administration in May, when David Norquist, now the DoD comptroller, testified at his Senate confirmation hearing that the department had spent enough time doing limited-scope audits in preparation for the full audit that’s yet to come.

“This approach has diminishing returns,” he said. “I recognize it will take time for the department to go from being audited to passing an audit. Everything you have heard about the size and complexity of the department is true, and this legitimately makes any endeavor, like an audit, harder. But that is not a reason to delay the audit. It is the reason to begin.”

From Grassley’s point of view, DoD has already tried that approach – and failed. Norquist’s current plan is on “shaky ground,” he said.

While several DoD elements, including some within the Defense Accounting and Finance Service, the Army Corps of Engineers and the Defense Information Systems Agency, to name a few, have already earned clean opinions, the Marine Corps was supposed to have become the first military service to pass a partial audit.

With some fanfare, DoD officials announced that the Corps had achieved a clean opinion on its statement of budgetary activity in 2014, but the DoD Inspector General had to revoke that opinion after it became clear that the Marines’ documentation left out a significant amount of DFAS-managed transactions in Treasury Department suspense accounts.

Under DoD’s current audit plan, the Marines are once again scheduled to lead the way. During this fiscal year, they became the first of the military services to undergo a full-scope independent audit, not just an SBA audit. The results are expected by the end of the calendar year.

But Grassley is not optimistic about the outcome, either for the Marine Corps or for DoD as a whole until the department fixes what he views as its “deal-breaking” weaknesses.

“This is where we’ve been before,” Grassley said. “You say you’re audit ready, but you’re light years away from a clean opinion. It takes you to nowheresville. Why go there when you know what you’re going to find? The end result has been mostly waste: $32 million for five premature [Marine Corps] audits. DoD is big, big, business for these auditing firms, and what do we get? No clean opinions.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jared Serbu is deputy editor of Federal News Network and reports on the Defense Department’s contracting, legislative, workforce and IT issues.

Follow @jserbuWFED

Related Stories