Federal HR hasn’t truly recovered from mid-1990s downsizing era, MSPB finds

According to new research from the Merit Systems Protection Board, downsizing and decentralization within federal HR over the last three decades have created a void...

Agency human resources shops are still struggling to find their footing after the National Performance Review of the mid-1990s, when the federal government shed thousands of positions in pursuit of a more efficient and strategic HR business partner.

The downsizing and decentralization of federal HR over the last three decades have created a void that many agencies haven’t quite recovered from, and emerging technology has yet to fill the gap, according to the Merit Systems Protection Board.

MSPB detailed these findings in a new research brief based on its own surveys, interviews and analysis of Office of Personnel Management data.

The Clinton administration, which launched the National Performance Review (NPR) in an effort to create a government that “works better and costs less,” wanted federal human resources to have a more prominent seat at the management table. Rather than focusing on transactional HR work, the NPR envisioned a future where individual human resources specialists would help agency leadership make mission-oriented plans for recruiting, developing and managing people.

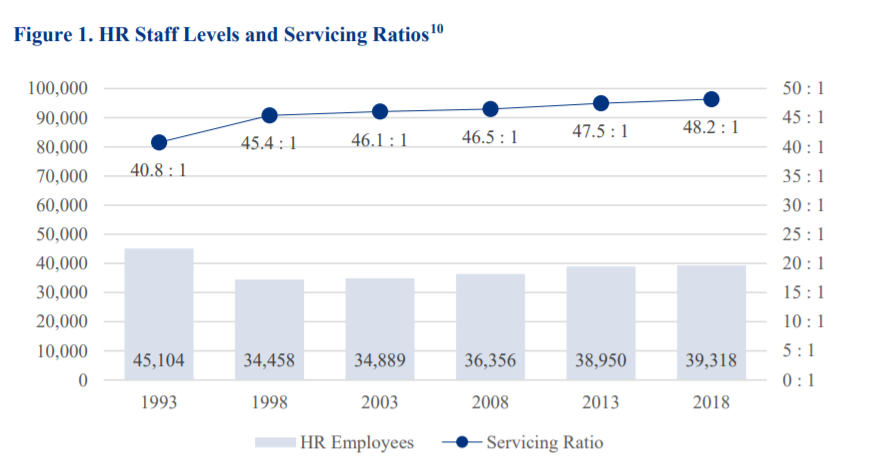

As a result of the NPR, staffing levels at federal HR offices dropped anywhere from 24-to-40% between 1993 and 1998, while the Office of Personnel Management lost more than half of its workforce, according to the MSPB.

Though agencies have slowly hired more HR specialists since the mid-1990s downsizing era, most HR specialists are servicing a greater number of their organization’s employees than they were in 1998, when the total federal human resources workforce stood at a low of 34,458.

Today, one HR specialist services about 48.2 of their agency’s employees, compared to a 45.4:1 ratio in 1998.

The federal HR workforce itself has also changed. Most civilian agencies have more HR specialists today than HR assistants, though the mix between the two is more even at the Pentagon and the Department of Veterans Affairs. HR specialists at civilian agencies are also higher-graded today than they were in the mid-1990s.

According to the MSPB’s analysis of OPM data, 56% of HR specialists in 2018 were ranked at GS-13-15, compared to 41% in 1990.

Automation and other IT advancements were supposed to help agencies shoulder the staff cuts and take on more meaningful, strategic HR work.

But IT hasn’t quite transformed federal human resources as originally intended. HR specialists told the MSPB they spend a significant time on transactional activities that aren’t necessarily strategic.

“Although automation makes some tasks easier, it has not eliminated the need for HR assistants, because it has not eliminated all the processing work that they once performed,” the MSPB report reads. “Second, many specialists said that they are now overwhelmed by lower-level tasks such as processing personnel actions and data entry. Those tasks reduce the time available to engage and consult with managers.”

Too little time for training, meaningful promotions within federal HR

The federal HR has also been slow to evolve, as few agencies are injecting fresh talent into the workforce. According to an MSPB analysis of OPM data, agencies hired the vast majority — 74% — of their new HR specialists from within government, while 26% were external hires. About 86% of the internal hires came from within the same agency.

Though the MSPB acknowledged promoting HR talent from within has some advantages, the practice is only effective when agencies have assured promoted employees have the training and the skills they need to be successful.

“Responses to our agency questionnaire also indicate that much HR staff training is neither systematic nor deep,” MPSB said. “When we asked chief human capital officers if they had a comprehensive HR training plan or program, the majority of them said they did not. A frequently cited reason was a lack of resources.”

In addition, some HR promotions have occurred far too quickly, specialists told the MSPB. HR supervisors are often too overwhelmed with their own work to argue why someone shouldn’t be promoted, paving the way for automatic, step increase promotions to continue without much thought.

Beyond downsizing and making federal HR more efficient, the National Performance Review also strove to decentralize human resources decision-making to the agencies themselves. The theory, according to the NPR, was that such decisions were best made by the people closest to their agency’s individual missions, not a centralized HR entity like OPM.

“The centralized expertise and leadership that resided in OPM do not appear to have been restored, and HR staff recruitment, selection and development are managed by individual agencies,” MSPB said. “The interviews provided little indication that agencies have cultivated deep expertise or broad thinking in their HR workforce. A common belief was that HR staff do not understand the theory or principles behind the processes; they know only that they were told to do things a certain way.”

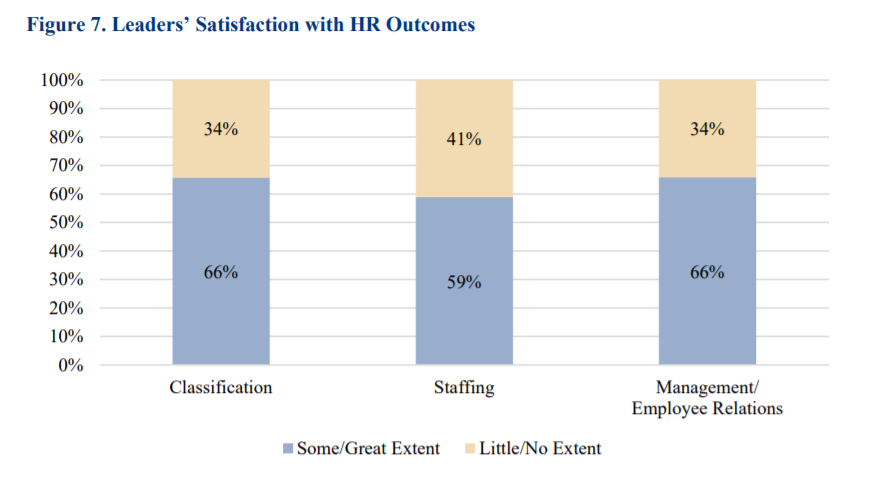

An MSPB survey found agency leaders’ perceptions of their HR service and staff were mixed.

Though most agency leaders said their HR specialists were knowledgeable, fewer departmental leaders said they were effective. While 75% of agency leaders, for example, agreed their HR specialists were knowledgeable of federal classification rules, 64% said they were effective in that particular area.

In addition, one-third of agency leaders said their HR specialists had too narrow of a view on federal personnel regulations and rules, and 48% said they knew how to find creative solutions within the bounds of the law.

“The vision for federal HR since the 1990s has been that HR staff would become consultants and advisers instead of enforcers,” the MSPB report reads. “Yet when we asked managers how effective their HR staff were as consultants, only 62% of managers thought their HR staffing specialist was effective in that capacity. During group interviews, many HR specialists stated that they had neither time nor resources to consult with managers on a regular basis.”

Agency supervisors and HR specialists also lack mutual trust and respect. At one agency, HR staff told the MSPB they believed they were obligated to give managers the answers they wanted to hear.

“These staff described line supervisors and managers who would contact higher-level HR managers until they received the answer they wanted and HR managers who would frequently overrule HR specialists’ judgments, leading to demoralization,” the MSPB report reads.

The frustration, however, carried both ways.

“For their part, many supervisors and managers believed that HR staff were needlessly inflexible and viewed them as roadblock,” the MSPB said. “Supervisors described HR staff who did not respond to their requests and complained about poor quality referral lists and a lack of consulting. Sometimes, supervisors were just told ‘no’ without any explanation.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED

Related Stories