How 3 agency leaders try to mitigate burnout, stress for federal employees

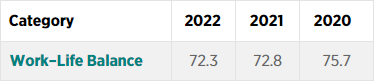

Work-life balance is one area in particular where agencies are starting to see signs of stagnation among their employees.

Many agencies are facing stagnating employee engagement scores and declining satisfaction, even among some of the best places to work in government.

With an increasingly hybrid federal workforce, work-life balance is one area in particular where agencies are starting to see signs of decline among their employees.

The Partnership for Public Service, in its initial release of the 2022 Best Places to Work in the Federal Government rankings, reported that employees’ scores for their agencies’ work-life balance decreased slightly — a trend that has continued for the past few years.

Maintaining work-life balance is important for anyone, but the overall scores can vary depending on an employee’s age. Data from the Partnership for the 2021 rankings also found that federal employees in Generation X, those currently between ages 40 and 59, had the most negative perception of their work-life balance out of any age group in the federal workforce.

Now more than three years after the COVID-19 pandemic started, human capital leaders are grappling with more long-term ways to improve employee satisfaction and engagement — and part of that means considering how to manage burnout and stress for federal employees who may feel overworked.

Improving employee satisfaction is far from simple, but for many, it starts with striking a balance between productivity and engagement.

“It’s always about managing expectations — knowing and explaining to your staff that there are going to be times when we need to exceed productivity. And there are going to be times when we may have to fail because we don’t have adequate staffing,” said Dexter Brooks, associate director for the Office of Federal Operations at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, during a GovLoop event Wednesday. “[Try] to bring in some semblance of fairness in the way that you’re doing your work so that you don’t create the burnout that we see too often.”

The onus often falls to agency managers to take the lead on finding workforce gaps — in areas like skills, technology and training — and then making corrections where needed. Asking for employees’ feedback on where there are gaps is important for reducing stress and burnout, while improving productivity.

After communicating with staff and getting feedback on where there is room for improvement, “see how much of that you can get [from your agency] — whether it’s additional money for overtime, or hiring additional people,” Eric Dilworth, deputy chief human capital officer at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, said during the event. “Get that feedback from your team and then try to meet some of those areas that they’ve identified. When you show that you’re willing to be all in for your team, they normally come together.”

For Dilworth, helping employees mitigate stress and burnout starts with figuring out how to prioritize the goals of both leadership and staff simultaneously.

“One of the first things that I do is understand my leadership’s priorities, and see how that affects my team,” he said. “I relay those priorities to my team and … get a clear understanding from them. That’s not done in just one meeting, there may be some feedback and back and forth. But then we come to a real clear understanding of what the priorities are.”

“If you don’t prioritize, you’re setting yourself up to fail,” Dilworth added. “You also cause a lot of undue stress on yourself and your team.”

For Dilworth’s team, one recent challenge was the steep goal of trying to hire 1,000 new employees in a one-year period. A lot of it came down to getting input from the team and communicating regularly about the reason behind the hiring spree.

“Communicating back and forth and getting the team’s input on how we’re going to execute that priority was key — taking their input in and really using it,” Dilworth said. “By doing those things, it really set up expectations and really had a better chance of obtaining the desired outcome.”

Regardless of how heavy the workload is, the overarching key component for leaders was communication.

“I think in government, we all understand you sometimes have to manage workloads with limited resources, so it’s always important to have a clear understanding of your productivity goals,” Brooks said.

It’s no surprise that the pandemic changed how agency leaders manage their staff. During the earlier days of the pandemic, some agency leaders were focused on maintaining a sense of collaboration, but now much further along, changes in leadership style are more long-term.

“We’re getting back to a point where we can once again connect with people in person, collaborate with them in dynamic ways and think strategically about the longer-term future of how we work and how we live — and how that’s combined,” said Katy Kale, the General Services Administration’s deputy administrator, during the event.

“We are continuing to evolve how and where we work, and there’s still work to do in that space,” Kale added. “A lot of people are turning to one another, talking about what’s next, they’re taking more trainings to give them more tools and building new muscle about how to be more efficient and lead in this new future.”

The Office of Personnel Management has taken up the challenges of hybrid work operations as well — the agency is offering free training sessions to federal employees on best work practices for hybrid environments, with a mix of in-person and virtual work.

“It’s about how do we do our jobs to the best of our ability while working in hybrid environments, while taking care of our teammates and taking care of ourselves,” Kale said. “It’s how do we combine technology and space and our talented people in the best ways, so that we can get our work done in a successful manner? Not just checking a box, but actually really making a difference.”

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Drew Friedman is a workforce, pay and benefits reporter for Federal News Network.

Follow @dfriedmanWFED