Secret Service to punish agents after unauthorized peeks at congressman’s file

Secret Service Director Joseph Clancy says the agency is in the process of disciplining agents involved in the scandal, but some lawmakers and watchdogs say the...

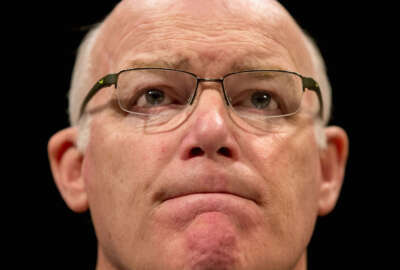

The Secret Service director, appearing deeply embarrassed, apologized again Tuesday for actions of agents working under him and told Congress that dozens were being disciplined for their efforts to discredit a congressman investigating misconduct inside the agency.

“A hearing like this puts a definitive stamp on our failures,” Joseph Clancy told members of the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Subcommittee on Regulatory Affairs and Federal Management, and the House Homeland Security Subcommittee on Oversight and Management Efficiency. “I’ve heard the comments made today — ‘reprehensible, disturbing, embarrassing.’ I agree with everything that has been said here today and my workforce does as well.”

According to the Homeland Security inspector general, more than 40 Secret Service employees, including supervisors, were involved in an attempt to embarrass Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R-Utah), the chairman of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, following a hearing in which Clancy testified before Chaffetz’s committee. They found, opened and shared Chaffetz’s failed application for a Secret Service job in 2003, an IG report found. One employee was accused of leaking the file to the media.

The Homeland Security Department has proposed 3 to 12 days’ suspension for approximately 42 employees who fall under the General Schedule, Clancy said. DHS has yet to announce disciplinary measures for the senior executives involved. Those could range from a letter of reprimand to removal, he said.

Some lawmakers suggested that the department was too lenient and slow to punish employees for the incidents, which occurred in early spring.

“Should we be looking at the law and making sure agencies have enough power to hold people accountable?” said Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.)

“I think the excepted service would allow us to speed up the proposals and the discipline process. I know sometimes we are delayed in the process,” Clancy said, adding he also would like to act more quickly.

Clancy said the department was meting out punishment based on a new table of penalties that is in line with other agencies. He said the department also considered employees’ work histories.

“Some of these people have spent 28 years with no discipline in their history. Some of them self-reported. They’re obviously all very remorseful. We do look at the whole picture, the whole person and their career,” he said.

Agents ignored multiple warnings that personnel records should be accessed for authorized purposes only, said Inspector General John Roth. They should have known that handling Chaffetz’ file violated the Privacy Act, DHS and Secret Service policies, he said.

Related Stories

But some of them did not think it was wrong because they saw the information stored in the database as Secret Service property.

“They called it ‘our database,'” Roth said. “Others didn’t understand that it was wrong until after they did it and they said, ‘Gee, I probably shouldn’t have done it.'”

Gary Durham, then the special agent in charge of the Indianapolis field office, wanted to know why Chaffetz had — in his view — been tough on Clancy during the March hearing, Roth said.

“He, out of idle curiosity, accessed the database himself to discover that Chairman Chaffetz was a former applicant. He did nothing with the information,” Roth said. “There are a number of examples like that.”

He could not determine whether Secret Service agents had accessed other individuals’ files improperly.

Unauthorized access to sensitive files a governmentwide problem

Unauthorized access of files is the most common information security problem governmentwide, said Joel Willemssen, the managing director of information technology at the Government Accountability Office, who testified alongside Clancy and Roth.

“Too many people have access to things they don’t need access to. It’s not part of their job description. They don’t need to know but yet they have access,” he said.

Agencies can safeguard data from unauthorized access through both audits and algorithms, which can be done automatically, he said.

The Secret Service is not the worst example of unauthorized access to sensitive information, he said. In particular, the Veterans Affairs Department, Social Security Administration and Education Department pose the greatest concern because their databases hold a vast amount of personally identifiable information on Americans, he said.

No agency controls access to information well enough to serve as a model for others.

“That’s somewhat depressing,” said Sen. James Lankford (R-Okla.)

Willemssen agreed, noting that recent breaches of Office of Personnel Management databases had underscored the problem. On an optimistic note, he said, they had propelled the White House to make information security a governmentwide priority, which multiple warnings from GAO had failed to do.

“When we first announced the information security area as high risk, I was told, ‘You’re Chicken Little; the sky is falling,” he said. “I don’t hear that anymore.”

Secret Service closes database at risk

Clancy said he was confident that Secret Service agents had gotten the message. The agency was sharing disciplinary information with all employees. Furthermore, it had solved technical problems by migrating personnel records to a new database that allows administrators to better control access, Clancy said.

Chaffetz’s file had been stored in a 32-year-old system called the Master Central Index. Employees who could log onto the system had access to all of the data it held, regardless of whether or not they needed it. Now 95 percent of those employees have lost their access to applicants’ files, Clancy said. The files will be purged from the database every two years, he said.

Lawmakers said they were concerned that the Secret Service was treating this as an isolated incident, rather than one in a string of problems involving Secret Service agents. Recently, agents have been accused of falling asleep while on duty, appearing drunk at security incidents and attempting to solicit sex from a minor.

“Every incident that we know of, there seems like there wasn’t an adult in the room, there was no one who provided that voice of saying, ‘Hey guys, this is not the way to do this. We have a responsibility that’s higher,'” said Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D-N.D.). “It seems like all of this has happened with a great impunity. It’s either, ‘You can’t touch me’ or ‘It’s OK to do this.'”

Clancy, who worked for three years in the private sector after a long career at the agency, said he was trying to break up its insular culture. Traditionally, agents have held key positions regardless of their expertise. The new chief operating officer is a civilian, he said. Other leaders, including the chief financial officer, chief technology officer and chief strategy officers, have come from the outside too, he said.

The agency is also hiring new agents and officers to reduce the amount of overtime that employees now work. That should improve morale, he said. The scrutiny of agents’ misdeeds has also helped raise morale by sending a message that misdeeds will not be tolerated, he said.

“Unfortunately, it takes these significant errors — misconduct — to resonate sometimes with our people,” he said. “But I have to say one thing: Less than 1 percent of people are involved in this misconduct; 99 percent are doing the right thing and working very hard.”

The Associated Press contributed to this story.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.