WH cybersecurity coordinator seeks more ‘naming and shaming’ of hackers

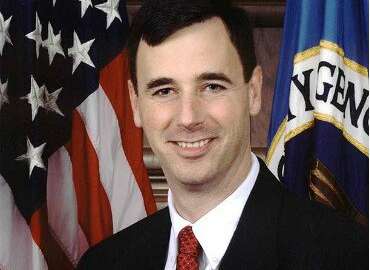

White House Cybersecurity Coordinator Rob Joyce said Monday that the federal government plans to strengthen its cyber deterrence policy this year through some of...

Looking back on an “unprecedented year of threats” that included WannaCry and the Equifax breach, the White House’s cybersecurity coordinator said Monday that the federal government plans to strengthen its cyber deterrence policy this year through some of its closest international partners.

In order to play a more offensive role in cybersecurity and give hackers more reason to believe they’ll be caught red-handed, White House Cybersecurity Coordinator Rob Joyce said the federal government needs to be able to hunt down digital paper trails that may exist overseas.

To do that, Joyce said he’s urged lawmakers to craft legislation that would make U.S. companies responsive to foreign subpoenas, and allow the federal government to pull offshore data from U.S.-based companies.

“While we’re all concerned about cybercrime and the security of our networks, we’re also really concerned about other countries around the world really creating this convoluted patchwork of laws and regulations that impact our ability to move data,” Joyce said at the ICIT Winter Summit in Arlington, Virginia.

While some foreign governments restrict the free-flow of information across the internet in more overt ways, like blocking public access to entire websites, Joyce said the federal government has also encountered more benign hurdles when it comes to obtaining cyber threat information.

“If we bring a warrant through the courts to Microsoft and say, ‘I need information about this hacker involved in this commercial espionage,’ Microsoft is happy to supply the data that they hold in the cloud in the U.S. But if some of that data is in a cloud in Ireland, they turn around and say, ‘I don’t have the authority to reach into Ireland and pull that data back,’ even though it’s Microsoft’s proprietary data,” Joyce said in an example outlining the problem.

On an increasingly fragmented internet, where malicious actors continue to see more reward than risk in targeting U.S. government systems, Joyce said cybersecurity officials need more information sharing to track down and punish individuals or foreign governments for hacking.

“It really is about shooting their motivation and mentality that says, ‘I can get away with this.’ And from the U.S. government’s stance, we have a series of tools we can use,” he said.

Those tools include diplomatic levers such as indictments and arrests, sanctions and other “naming and shaming” methods.

“Today, doing bad things on the internet generally brings you more value than the expected cost. People are not worried about getting caught. Countries are not worried about the impact of doing malicious things on the web.”

If lawmakers on Capitol Hill do introduce a new information-sharing cybersecurity bill, Joyce said foreign governments won’t have carte blanche in obtaining sensitive cyber information from U.S. companies. The deal currently under consideration would give the attorney general and secretary of state the authority to review the legal standing of each request from foreign governments. The rollout would likely begin with close international partners like the United Kingdom.

“The big thing about this is that our legal structure is now not responsive to the way the plumbing of the internet is wired,” Joyce said.

White House looking to shared services solutions

Looking at cybersecurity across the federal government, Joyce said his office has looked more at shared services to centralize the cyber workforce, much like how some agencies share human resources and payroll services.

From a security standpoint, Joyce said a shared services model prevents any agency program, no matter how small, from being the path of least resistance for hackers to break into.

“I can have the Bureau of Land Management run their email server, but the chances are that’s a one- or two-man shop really responsible for that,” Joyce said.

The problem, however, is attracting top cyber talent to that kind of office, when larger agencies and the private sector continue to compete for the same pool of IT workers.

“But I still need that protection inside those government networks because one chink in our armor means somebody’s inside the fence, and then they start to move and propagate and get to other places that I care a lot about. So with that, what we’re trying to do is to push together some of the common defenses of the government and make much larger teams,” Joyce said.

Coming soon: Trump’s FY 19 budget proposal

More than half a year into President Donald Trump’s cybersecurity executive order, Joyce said agency leaders and their deputies have taken more ownership of the cyber risk vulnerabilities that exist within their organizations, and are looking for Trump’s fiscal 2019 budget request to reflect the White House prioritizing of cybersecurity spending.

“We’ve talked about some of the cyber intrusions we’ve had and we’ve talked about the issues of looking forward at the budgets to make sure that we have their attention, to prioritize their resources as they’re making decisions,” Joyce told reporters on Monday.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jory Heckman is a reporter at Federal News Network covering U.S. Postal Service, IRS, big data and technology issues.

Follow @jheckmanWFED

Related Stories