Security clearances, cyber doctrine top list of Warner’s national security crises

The backlog of security clearances in the federal government makes it harder to perform classified work, while the lack of a cyber doctrine makes it harder to...

As vice chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Mark Warner can talk at length about national security crises. And when he does, two particular subjects are currently near the top of his mind: security clearances and cyber warfare.

During a June 22 Northern Virginia Technology Council event at George Washington University’s Science and Technology Campus, Warner said the security clearance backlog is currently around 740,000 people, and that the average clearance takes 540 days.

“We have to do a better job of security clearance,” he said. “This issue, which has dramatically grown since about 2014, this is a national security crisis. The good news on this is that there’s nothing partisan about it … Director of National Intelligence Dan Coates says the system needs to be replaced. Not repaired, but literally reimagined.”

And Warner has a few ideas of how to do it. In the recent NDAA bill, he managed to include a few amendments to address the issue. One sets goals to get secret clearance investigations down to 30 days, and top secret down to 90. Another would establish reciprocity among contracts.

“The thing that we’ve discovered is if you’re a contractor, and you’re moving from one contract to another within DHS, it can still take 100 days, even though you’ve got a DHS clearance,” Warner said.

Other ideas that didn’t make it into the NDAA, but Warner is still pushing, include:

- Making agencies publish the actual costs of clearances

- Ongoing examinations rather than 5-year updates

- Allowing interviews to be conducted via Skype

- Better access to college and criminal records

Those last two would be major time-savers, Warner said. The Skype interviews would allow investigators to do far more interviews each day, since they wouldn’t have to spend as much time sitting in traffic. Similarly, investigators currently have to visit a subject’s college in person to obtain their transcript. And some states don’t share criminal records with the federal government, so investigators have to travel to the relevant jurisdictions to access those.

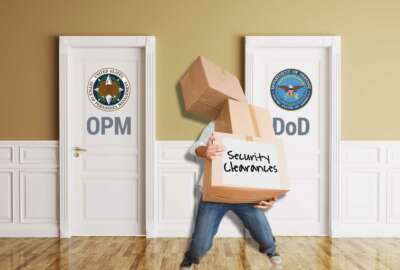

Warner thinks current plans to transfer the responsibility for clearances to DoD could help, if it’s managed properly.

“Putting it all under one roof may make sense, and DoD — Secretary Mattis, I have a lot of faith in him,” he said. “But what I don’t want to have is transference become another bureaucratic stumble. Since the vast majority of security clearances still fall under the DoD umbrella, if they will make this a priority, that would be good. But time will tell.”

In addition, Warner hasn’t forgotten National Counterintelligence and Security Center Director William Evanina’s promise to reduce the backlog by 20 percent by the end of the year.

“I’ve had a commitment that we are going to get rid of over 100k backlogged clearances before the end of the year,” he said. “And I’m going to hold feet to the fire, the folks in the intel community, to make that happen.”

Still pushing for cyber warfare guidelines

Meanwhile, Warner is also pushing for the government to establish a clear set of guidelines around what it considers cyber warfare, and how it will respond.

“Our nation has never had a cyber doctrine,” he said. “We’ve never clearly articulated what is our strategy, what would be our response. That failure to have a cyber doctrine has basically meant — particularly not so much for Iran, North Korea, ISIS and other smaller secondary nation-state threats, but for near peer adversaries like Russia and China — our failure to articulate our doctrine, our failure to set out our cyber norms, and frankly our concern about any cyber escalation has meant that those near peer adversaries have felt that it is open season on attacking our country, stealing our intellectual property, with very little fear of repercussion.”

Latest Technology News

He said the world has international agreements around the use of chemical weapons, land mines, and other weapons of conventional warfare. But no such thing exists around the use of cyber warfare. He said he’d like to see a treaty, ideally, but at the very least some kind of agreement about what kinds of attacks, and what kinds of victims, are off limits.

Otherwise, he says the U.S. will continue to be a victim of cyber warfare, because it doesn’t want to cause a cyber escalation. The U.S. has to begin punching back, he said, and be very clear about when that will happen.

“While we have extraordinary offensive cyber tools, we have been very unwilling to use them,” Warner said. “Occasionally, hypothetically, maybe we have punched back on second-level nation states. But on near peer adversaries — again, Russia and China in particular — I think we have been so afraid of using our cyber tools in any kind of offensive capability against those nations because we have been terribly afraid of cyber escalation. Shutting down Moscow for 24 hours with no power would be a problem. Shutting down New York for 24 hours with no power would be a crisis.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Daisy Thornton is Federal News Network’s digital managing editor. In addition to her editing responsibilities, she covers federal management, workforce and technology issues. She is also the commentary editor; email her your letters to the editor and pitches for contributed bylines.

Follow @dthorntonWFED