Federal offices of the future could resemble your back patio

In the future, federal offices could be more like patios - where furniture is adjustable and moveable for whatever task or project is at hand, say experts at the...

Workplaces have never been egalitarian. But when what we nowadays call knowledge workers first began to occupy offices in large numbers, they occupied a two-class system. Either you sat at a desk amidst a sea of desks, or you had the office, dais, or balcony overlooking and supervising everyone else.

Then around 1960, the cubicle caught on “and we shifted away from this two-class society,” the General Services Administration’s Kevin Kampschroer told Federal News Radio.

There were cubes, corner offices, offices along the walls, inner and outer offices — all of it pretty much locked-in without much flexibility unless management was willing to invest in new build-out.

Kampschroer is an expert in federal office space. His official title is director of the Office of Federal High-Performance Green Buildings. He’s researched and studied offices and how people react in them for years. He and staff expert Judith Heerwagen discussed how offices are changing as part of Federal News Radio’s special report, The Federal Office of the Future.

Heerwagen said the big change is in how organizations’ leaders see the workspace—less as a place to squeeze in workers and more of a flexible environment in which the layout changes to support the specific mission or even a particular phase within a project.

“We’re seeing organizations adopt a wide variety of models to support their individual missions,” Heerwagen said. “They’re more conscious of the workplace as a strategic value.”

As Kampschroer and Heerwagen see it, the office is undergoing another big shift right now, thanks to electronic mobility. He recalled the arrival of PCs in big numbers beginning in the mid-1980s. With their steel enclosures and big monitors, the things weighed close to 100 pounds. Then the machines became attached to a network. That, plus their sheer weight, pretty much tethered people to their work stations, whether cubicle or office. In that sense, a PC in a cubicle produced the same work habits as a drill press mounted to the floor of a factory.

The pair point out that mobile devices and ubiquitous Wi-Fi have helped reverse that model. But, Kampschroer said, other factors have also played into the trend back to the open office plan that GSA itself adopted at its headquarters building.

GSA began studying the idea of an open office space for its employees as early as 2001, Kampschroer said. The agency researched usage patterns of all types of spaces and rooms within an office.

“We found, systematically, that the space – and we studied it every minute for over two weeks – and we found that 50 percent of the time, there’s no one there. No matter whether a conference room, desk or cubicle,” Kampschroer said.

Together those factors (research showing usage, mobility and changing work cultures) are bringing back the open office dotted typically with small enclosed spaces for conferences or quiet thinking.

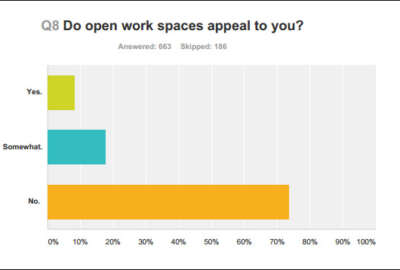

Kampschroer said studies show that noise is the distraction most often cited by employees in open plan offices. Yet a counter-intuitive phenomenon also occurs.

“We did measurements at different cubicle heights and what we found was that, acoustically, when the partitions are low and you have visual connection with the other people in the space, the overall sound levels are measurably lower.” It could be that without the ability to hide visually behind cubicle walls, people become more reserved in the noise they make.

“People also say they learn things from accidental conversations in open space. Yes, it’s bothersome, but on the other hand yes, it’s useful,” Kampschroer said. “In one case study, 95 percent of the people said there weren’t enough conference rooms. But we also found that 70 percent of the time the conference rooms were empty.”

In other words, it seems management is pretty much obligated to provide space for quiet concentration or small meetings, even if they aren’t occupied all that much.

The next wave of office design will bring modular units that employees themselves can move and reconfigure without the need for tools, almost like patio furniture.

“We’re going to see transformations so offices become more like a stage set, transforming for each stage of a project,” Heerwagen said.

Regardless of what type of office plan an organization chooses, when groups or bureaus or whole agencies move, it’s wise to let people see and rehearse their movements in relation to the new surroundings ahead of time, Kampschroer and Heerwagen said.

Ideally, include employees in the decisions about the space. That brings more acceptance later. Kampschroer said people closest to the workflow will have the most relevant ideas for how to lay out the surroundings.

He cited instances in GSA’s remodel where files relating to contracting were stored in three separate places. When they were combined in a new office, it reduced the number of required file cabinets and boosted efficiency. People now spend less time hunting for and retrieving files.

Once the space design is finished, don’t overlook the people and culture factor.

“I used to hate the term change management…but, in fact, it’s hugely important,” Kampschroer said. “It’s a huge mistake to expect people to confront a new space and figure it out for themselves.”

He said management should not consider it a luxury to let people spend time in the new space before it actually opens for business. He makes the analogy to new software. Better to let people get a feel for it beforehand rather than dump it on them, or them into it, when the pressure is on.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Tom Temin is host of the Federal Drive and has been providing insight on federal technology and management issues for more than 30 years.

Follow @tteminWFED

More from the Special Report: