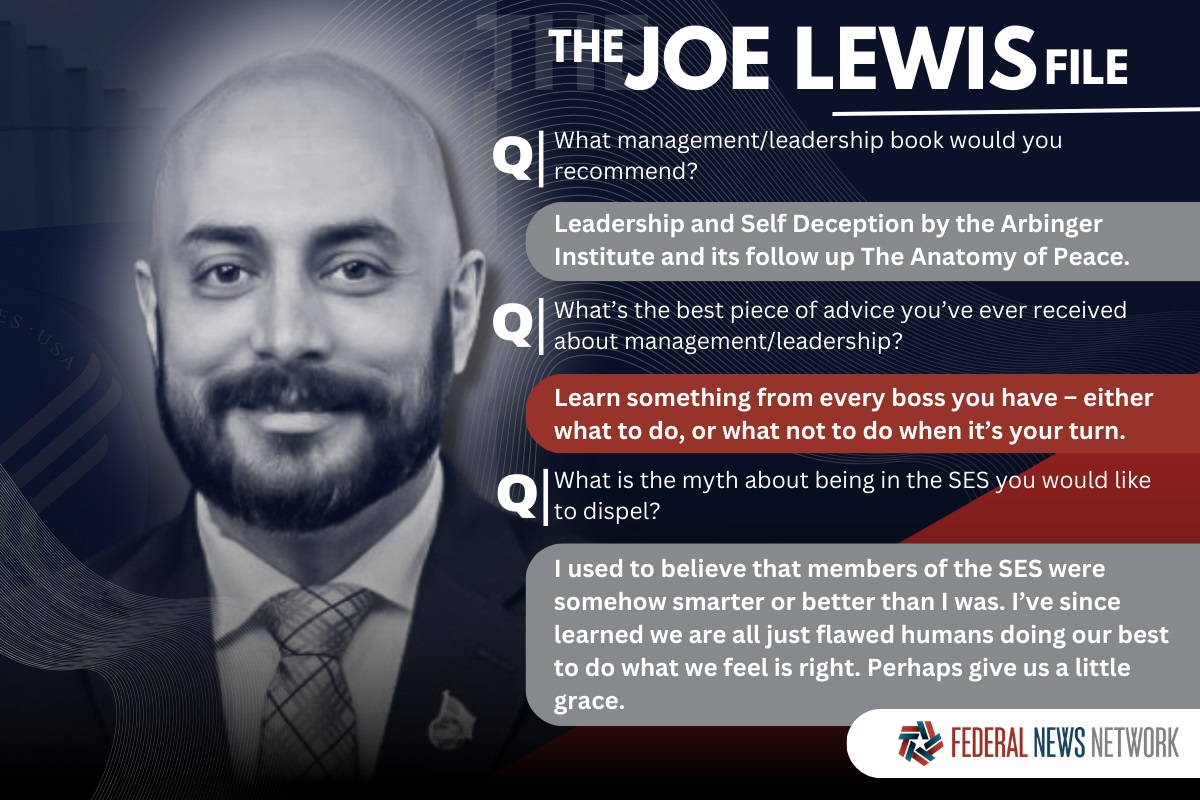

In reaching his career goal, Lewis shares how to navigate the path to the SES

Joe Lewis, who joined the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as its chief information security officer in January 2023, said joining the Senior Executive...

Just about a year ago, Joe Lewis took the plunge into the Senior Executive Service.

It was a leap of faith in many regards because while taking an SES position is good for your ego, good for your career, in some respects, and good for your agency, it can be hard on you, your family and eventually your checkbook if you get caught in the pay compression challenge.

Lewis, who joined the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as its chief information security officer in January 2023, said obtaining the SES level always has been a career goal.

“I didn’t do this for ego reasons, but more because I felt like I could improve the quality of the work environment for a greater and larger number of people. As I ascended through different levels of my career, my sphere of influence grew, and my ability to improve relations for larger groups of people grew as well,” Lewis said in an interview with Federal News Network. “By virtue of that, the Senior Executive Service was always an ultimate goal. I believe that being a member of the Senior Executive Service gives you, probably, the greatest ability to affect the largest number of people in a positive way. It was a very early career aspiration of mine, and one I’m really proud to have achieved.”

Lewis’ decision is one many senior federal executive leaders are weighing. Many employees at the GS-14 and 15 levels are wondering if the move into the SES is worth it. Does the pain of management outweigh the gain of reaching the pinnacle of your career?

The decision for many GS-14/15s may be coming sooner than they thought as the number of SESers leaving federal service reached a four-year high in 2022. The Partnership for Public Service found in new data released in July 903 members of the SES left in 2022, which was second only to the 906 who left in 2018 and the second highest since 2005. Add to that, the fact that 38.6% of all SESers are 55 years old or older, more turnover in the SES is coming.

Federal News Network executive editor Jason Miller talked with Lewis about his year in the SES and why it was one of the best decisions he ever made. The following are highlights from that conversation to inform and educate other federal employees who are considering the move into the SES.

The application process

Most SES positions heavily favor the five-page resume format that covers both the executive core qualifications (ECQs) and the MCQs, the mandatory technical qualifications, for a position. It’s a fixed format. It has very, very specific guidelines. You build in how you meet not only the ECQs, but some of the sub competencies that exist there as well. First and foremost, if you’re at all considering an SES position, I would highly recommend searching out that five-page resume format and then working from that. In many cases, a lot of people hire writers to work on these five-page resumes because they’re so hyper specific, and they need to be individually tailored to the position you’re applying to much like every other federal job application that you do. That was kind of qualifier number one was getting that five-page resume making sure I could demonstrate that I could pass the ECQ as well as hit the technical competencies that were required.

Then you just apply like everybody else. I know a lot of people think that SES is all about who you know, but I was a cold applicant off the street. I applied and then there is a review of the resumes by an executive board. The executive board determines whether or not you’d have you meet the criteria to that would potentially pass OPM certification. Only those that have the potential get referred to the hiring manager. I applied in June and in early August I got to note that I had exceeded the qualifications by the executive review board, and then I was referred to the hiring manager. About a week and a half later, I had my first interview. It was a panel interview, and it was daunting, to say the least, being able to demonstrate core competencies from the ECQs perspective, but also demonstrate that I had the technical progress and the right perspective to be an executive was a real challenge.

I guess it went well because I got invited back for a second interview, completed the second interview, and then I was asked to have a conversation with the chief operating officer of the CDC, which I did a few weeks later. Then, most like everybody else, I got a tentative job offer. They let me know that I’d been tentatively selected, but the difference between the executive service and the general schedule is the tentative selection starts the process by which you write your ECQs. You do all these other things where all of your internal approvals have to be done first, before they’ll ever send your package to the Office of Personnel Management. My ECQs were sent to OPM and I got certified on the first pass. I will tell you that writing ECQs is no picnic. Plainly put, writing ECQs is almost like taking credit for the entire class’s worth of schoolwork when you’re in fifth grade. You cannot mention that you were on a team. You can’t mention the contributions of the others that were participating. It’s almost like you have to take credit for all of it. And it’s really, for me, it almost felt disingenuous that I couldn’t acknowledge the inputs and the successes of the team. But that’s not what it’s about. It’s very much about you telling your stories on how you meet or exceed the executive board qualifications. It’s a really challenging process.

In this case, I absolutely hired a writer. The way the writing works with ECQs is you meet with a consultant. I actually had drafts of my ECQs written so I provided those first, and this is really about telling stories and each ECQ you want to tell two specific stories about how you met or exceeded the core qualifications. I provided my first draft, the writer read them and then they came back with questions. It was like an interview and they asked me a ton of questions. Then they disappeared. They called me back and had more questions. I think we did this probably three or four rounds before I ever saw the first draft of my ECQs. But when it came out, I was actually frankly, very impressed because the ECQs are written in my own voice. It’s really, really kind of disconcerting, right, honestly, that they’ve gotten to know me that well in this period of time that they could write as if they were writing from my perspective. We refined, we iterated, we did some things and then we turned them in. The process is expensive. Hiring a writer is not cheap. Without quoting numbers, it was definitely in the thousands of dollars. But you’re making an investment at that point because you’ve already been selected for a position and if you don’t pass OPM certification, you cannot accept the job. So for me, I had already got selected for the job. This was my dream job. This was the job I wanted, so paying the money made the most sense in order to expedite the review has also made sure that I didn’t risk losing the position.

One year later

I think the biggest takeaway from my first year as an executive is, I can no longer be the smartest person in the room. The sheer breadth and depth of information that I would have to know in order to be a subject matter expert on all the areas in which are my responsibility, I would go crazy trying to be the smartest person in the room on all this. Instead, what I think I learned is that not only am I not the smartest person or I don’t want to be the smartest person in the room, I want to surround myself with good people that are subject matter experts who might have developed a bond and trust with that can advise me in order to inform my decision making.

The other thing is you need to think very strategically at this level. It’s easy to get caught in the hype or tactical, I’ve got this one problem that I need to solve. If I just do this one thing, I do that thing that I can solve that problem. If you’re not thinking strategically, that’s a tactical problem, and the way you solve it could have negative effects on other aspects across the office, across the agency, in my case, since I’m making decisions at the agency level, for the cybersecurity of the agency. So thinking strategically is a must. Having good GS-15 branch chiefs or direct reports is another must. One of the questions I’m often asked, and I think this is really good for people to know, is what makes a good GS-15? How do you be a good GS-15 that reports to an SES? How do you help enable an SES as a good as a GS-15? What I tell people to be a good GS-15, you need to be able to straddle the strategic and tactical realms. Simultaneously, you are operationally focused because your job is to implement, but you also need not to lose sight of the strategic because your decisions have the ability to affect others as well. So being able to be nimble and go back and forth from that operational to strategic is really key, as well as understanding how to build and maintain relationships with your peers, partners and stakeholders. Because if not, you’ll never be able to appreciate their equities and how your decisions will affect them. So learning to trust my GS-15, building that bond of trust understanding their subject matter expertise and then being okay not being the decision maker on everything and pushing the decision making down to the lowest level where it’s possible and then trusting people to do the job and then holding them accountable if they don’t.

Work-life balance

I’m very deliberate about my work-life balance. I carve out my own time, and work-life balance for me is good. It comes in waves, for sure. There are times where it’s worse than others. But I’m certainly not working 60 hour work weeks or anything like that.

Political appointees

Working with political appointees is interesting because they end up speaking with authority that maybe the career SESers don’t have. So what really ends up happening is that things happen faster when you’ve got a political appointee involved in something. They say, ‘Hey, wow, I worked for the deputy secretary, and she’s really interested in this’ and all of a sudden you’ve got resources, you’ve got commitments, things end up happening faster. So they are all well-intentioned people and usually, agents of change in a good way.

Advice for others considering the SES

First and foremost, be honest with yourself. Do you have the capacity, the capabilities to do the job? And remember, SES is a billet, it’s not a job. You’ve got to think about what’s the job you want and can you reasonably do that job? I think that we lack self-objectivity, a lot of times and really being brutally honest with yourself. I did not apply to a SES position two years before I started, when I was asked to apply because I didn’t think I was ready. So I think you should have that hard conversation with yourself.

Part two, be prepared to spend the money to do it the right way, hire the writer, get the resume, and get the ECQs done well. But also recognize that, in some agencies, SESers are preselected, as people know who’s going to get that job. And much like every other federal position, you may apply and never hear anything ever again, so it can be a little demoralizing and it can be a desensitizing. But perseverance is key if you truly have aspirations, then you should stick with it.

The last thing I’ll say is this, do it for the right reason. Don’t join the SES because you want to paycheck increase; don’t join the SES because you get to tell people what to do; don’t apply for SES jobs because you think that it’s going to look good on our civilian resume in a few years. Do it because you believe in the mission, believe in the organization, or like for me, do it because you want to make people’s lives better. You do it because your sphere of influence grows and you have the ability to make life better for more people.

Nearly Useless Factoid

80% percent of jobs are gained through networking and not a resume.

Source: Careerorigin

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED