The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs need to be reauthorized by Sept. 30 or federal research and...

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

In about 30 days, one of the longest running and most successful small business programs will expire.

The House will have 14 days in September with votes scheduled to reauthorize the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program when it returns to Washington, D.C. after Labor Day. Meanwhile, the Senate reconvenes on Sept. 6 and doesn’t spell out how many days it plans to be in D.C. and voting on bills.

To be sure, the fate of the SBIR program hangs in the balance of what Congress can do by Sept. 30.

If Congress doesn’t act, and it’s still a pretty big if at this point, the SBIR program would come to an end after 40 years. And this would be a travesty.

As Emily Murphy, the former administrator of the General Services Administration and long-time Hill staff member who worked on small business acquisition issues, wrote in April when she warned of the program’s impending expiration, the results of the SBIR program speak for themselves.

“Companies such as iRobot, Sonicare and Symantec are household names. Per the Small Business Administration, 70,000 patents and 700 public companies have resulted from the program. A recent study by scholars at Rutgers and the University of Connecticut looked at SBIR awards at the National Science Foundation and found that the SBIR program allowed the government to select risky but high impact ventures,” she said.

Now it seems likely that Congress will renew SBIR and all this consternation will have been for naught. But the question remains is whether they let it expire on Sept. 30 and renew it in October or November or whenever, and what impact that will have on agencies and industry alike will be significant. The threat of expiration already put agencies behind the time curve, Murphy said.

“Some small businesses will see an expiration as a sign the program isn’t stable, and may go elsewhere instead of becoming the next generation government contractors we need. They will look for other R&D funding paths that don’t promote federal mission needs, or may simply stick to traditional lines of business,” Murphy said in an interview with Federal News Network. “The government risks foreign countries closing the innovation gap, and warfighters, medical researchers, and others not receiving the support, tools and technologies they need to meet their mission.”

The authorization would impact the Defense Department in a big way, but it also would impact the National Institutes of Health, the Energy Department, NASA and the National Science Foundation.

At the heart of the matter is Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), ranking member of Small Business Committee, concerns about SBIR and how some companies game the system.

Paul outlined his concerns about of what he calls SBIR mills at a hearing last September on SBIR and its cousin the Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR).

“But only a select few win and have figured out how to make the SBIR program work for them and them alone. Some companies have been so successful in creating an entire business model and revenue stream that is solely for these grants they are known as SBIR mills. An analysis by the State Science and Technology Institute (SSTI) showed that from 2009 to 2019, 21% of the awards were made to the mills, which the institute defined as ‘firms who receive more than 40 phase one awards,’” Paul said. “Forty grants to just one company, may raise a few eyebrows as unnecessary and excessive and someone abusing the system. According to SBA’s public data, 196 businesses received more than 100 awards each. Some businesses received more than 900 awards. Sounds like somebody has figured out the system here.”

There is a lot of debate about whether SBIR mills really are a problem. As Paul highlighted, 21% of the SBIR awards from 2009 to 2019 went to these “mills,” but what he doesn’t mention is SSTI found 41.5% of the awards went to just one company and 56% of the awards went to companies winning two-to-19 awards, which is a pretty big spread. But this means a majority of all awards went to companies winning fewer than 20 total awards over a 10-year period. That is an average of two awards a year. Given the Defense Department made almost 17,000 individual phase 2 awards worth $14.4 billion between 1995 and 2018, two a year doesn’t seem too crazy.

A spokesperson for Paul said in an email to Federal News Network that ongoing negotiations are close to coming up with a compromise bill.

“Legislative aides for the Senate and House Small Business Committees and the House Science Committee have been in bipartisan bicameral negotiations every day for the last few weeks. As they were putting the final touches on compromise legislation to reauthorize the program, lobbyists for some of the worst offenders tried to stop Congress from taking action to curb SBIR mill abuse and destroy critical research security measures to secure the taxpayer’s investments in R&D from China, Russia, and other foreign influence,” the spokesperson said. “While our team has continued to push for a deal and work towards a compromise, Democrats are now the ones backing away from their own proposal to establish a benchmark for commercialization rather than a cap on awards.”

Sen. Ben Cardin (D-Md.), chairman of the Small Business Committee, offered a little more optimization about the likelihood of reauthorization.

“The SBIR and STTR programs harness the creativity and ingenuity of America’s entrepreneurs and innovators to solve the most pressing public health and national security challenges confronting our nation. Congress must reauthorize SBIR and STTR before they expire on Sept. 30 to avoid disrupting the research of small business participating in the program,” Cardin said in a statement to Federal News Network. “I will continue working in good faith with my colleagues to reach a bipartisan compromise that will reauthorize SBIR and STTR before it expires while protecting our national security and bringing more of the programs’ technologies to market.”

The Defense Department, which is one of the largest users of SBIR, offered its feedback on the reauthorization in July as well as comments on what the expiration would mean.

“Failure to reauthorize the [SBIR/STTR] programs will result in approximately 1,200 warfighter needs not being addressed through innovative research and technology development,” wrote Heidi Shyu, the undersecretary of Defense for research and engineering, and Bill LaPlante, the Undersecretary of Defense for acquisition and sustainment, in a letter to the House Small Business Committee. “Without a program targeted towards small businesses, the department will potentially lose access to talent and innovation inherent in America’s small businesses. In addition, uncertainty in the program will discourage small companies from doing business with DoD in the future.”

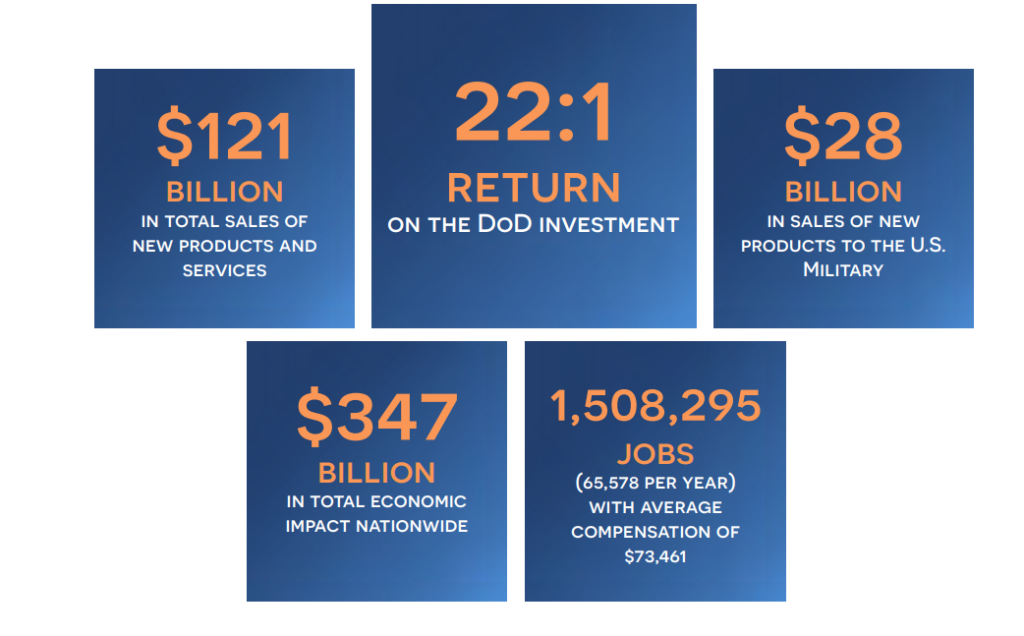

DoD says the return on investment through SBIR investments is substantial and increasingly making the program more valuable.

DoD, for instance, already put out a notice on Aug. 24 saying if Congress doesn’t reauthorize SBIR by Sept. 30, it will not move forward with its current broad agency announcement.

Eric Blatt, a lawyer with Scale LLP who advises startups that engage the SBIR program, said the program’s disruption also would mean companies possibly having to lay off employees, close altogether or seek funding from elsewhere, including China, which is a concern Paul brought up as a reason to hold up the reauthorization.

“SBIR is an important source of funding for companies, which are using this in addition to venture capital and other sources of funding. It’s very difficult to take an early stage company and bring the technology to market, and disrupting any source of funding can be disruptive or even fatal to that effort,” Blatt said in an interview with Federal News Network. “A lot of the technology that DoD wants to fund is hard to get venture capital dollars for because the DoD market is a difficult nut to crack and VCs look at that market as less attractive. This makes SBIR an incredibly important program to fund defense-oriented technology.”

Murphy, Blatt and other experts say concerns about SBIR mills are overblown. Yes, there will be some bad actors and they do need to be addressed and potentially removed from participating in the program.

“Any program of this size has underachievers, but the test Congress is promoting is a very blunt tool when we need a scalpel to determine who is producing results and who is not,” Murphy said. “There are better ways to address possible problems, such as requiring more reporting of the outcomes of phase II awards and if or when there are phase III awards or other types of commercialization.”

Blatt added many companies agree with the notion of adding more rigor to commercialization requirements of SBIR, some of which Congress is considering.

“Misuse of the SBIR program is not a significant issue in the scheme of things,” he said. “I don’t think reauthorization should hinge on this issue. It’s not a bad thing for companies to have incentives to do everything they can to turn their technology into competitive products. There are a lot of proposals on the table that have broad-based support and would further incentivize effective commercialization efforts.”

In the end, that’s what Sen. Paul is trying to do, make the program more effective and ensure the money that DoD and other agencies award is creating the next Pixar or global positioning satellite technology vs. the next Betamax or LaserDisc.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jason Miller is executive editor of Federal News Network and directs news coverage on the people, policy and programs of the federal government.

Follow @jmillerWFED