Exclusive

Feds lack confidence in agency cyber defenses, understanding

An exclusive Federal News Radio survey found that about 45 percent of public and private sector employees disagreed with the notion that their office or agency was...

The public and private sectors have had a year to learn from the cyber attacks the Office of Personnel Management suffered. But federal employees and government contractors are not confident their workplaces have a better understanding of, and stronger defenses for, cybersecurity.

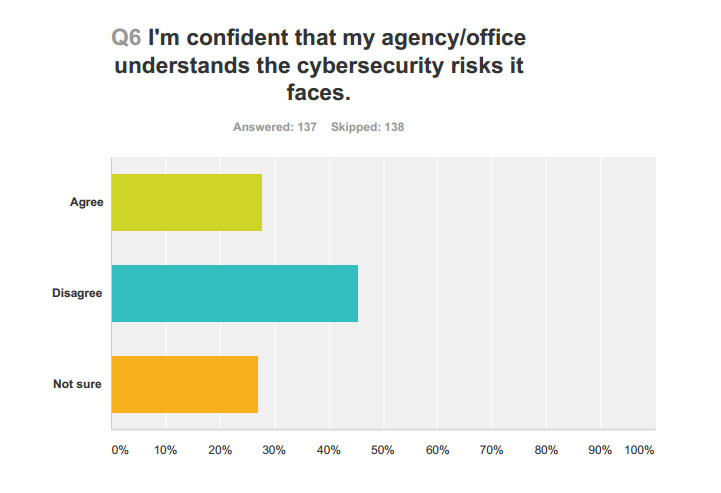

As part of the special report The OPM Breach: What’s different now, Federal News Radio conducted a survey that found only about 25 percent of respondents said they were confident their workplace understood cyber risks, while the remaining 75 percent disagreed or were unsure as to whether their office understood current data threats.

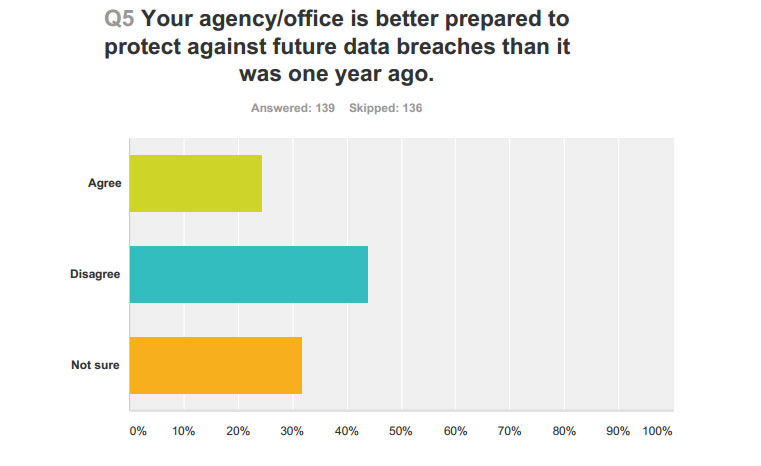

About 45 percent of public and private sector employees disagreed with the notion that their office or agency is better prepared to protect against future data breaches. An average of 16 percent said they felt their workplace was better prepared, while about 37 percent on average were not sure about their office’s preparedness.

“The FedGov as a whole is reactive, not proactive!” one respondent said.

“Our IT department is too broadly focused,” another survey taker answered. “They ARE trying to get their arms around the problems, but it’s a monumental task and they are fighting against longstanding cultural issues.”

A third respondent said, “I think we are taking steps in the right direction, but don’t have the personnel it takes to protect all of us. We need trained personnel that can appropriately handle the cybersecurity risks.”

Federal News Radio conducted the anonymous survey May 20-27. About 275 people responded, and of those, roughly one-third identified themselves as large civilian agency employees, while a quarter were Defense Department or intelligence workers. About 12 percent said they were contractors.

Roughly 45 percent of respondents said they worked with or in government for more than 25 years.

Federal News Radio also asked respondents to provide an answer to whether they lived within a 50-mile radius of the District. The ratio was about 60 percent to 40 percent for people who lived in and outside the D.C. area.

Fast responses, faster threats

Our goal for the survey was to get a sense from the public and private sectors whether they felt their information was safer and their officers more prepared to fight cyber hacks, in the year since the OPM data breach that impacted 22 million current and former federal employees.

An average of 55 percent of respondents said they did not think their personally identifiable information (PII) was more secure than a year ago, while the other 45 percent was split between unsure and believing the information was safer.

Respondents also were asked what they thought were the biggest cyber risks to their office or agency. The most common answers were aging or legacy IT systems, employees, lack of responsibility and accountability from leadership.

“My agency has minimal risks. The real risk is from OPM which is the worst managed, least productive part of the federal system,” one respondent said.

Another respondent said, “We need to think like hackers in order to establish effective security programs. The government’s heavy reliance on laws and regulations to establish cybersecurity approaches leaves every agency exposed. A good hacker would simply read NIST guidance, find the gaps in it and exploit the gaps.”

And yet another person said: “We lack personnel to update our systems in a reasonable time frame.”

About one-third of respondents said they hear their management or senior executives talk about cybersecurity in their office.

One respondent said leadership “has no understanding of cybersecurity, and relies exclusively on the word of the cybersecurity staff that all that can be done is being done.”

Another said management is “talking the talk but will not cut back mission for cybersecurity and there’s no place else to get it.”

“I don’t think I’ve ever even heard the term ‘cybersecurity’ where I work,” someone answered.

“Our leadership demonstrates that security is not a priority,” said one response.

“Top management only wants to do enough to ‘check the boxes’ rather than correct real problems,” another respondent said.

Costis Toregas, a lead research scientist with George Washington University’s Department of Computer Science, said it’s time for agencies to have “deep and extensive chats with employees.”

“It’s not rocket science, it’s leadership engagement in the cybersecurity issue,” Toregas said. “It means someone makes statements to his or her subordinates saying I understand the importance of cybersecurity, I’m doing the following things and here’s how you can help me.”

Respondents said when it comes to cyber efforts at an office or agency, most of that was done behind the scenes, or wasn’t clear to employees.

“All that has happened is that our IT leadership has made it increasingly difficult to even USE the system. We’re so well ‘protected’ that staff can barely function with routine tasks,” one person answered.

Despite most of the changes happening behind the scenes, more than 80 percent of respondents said they knew their office’s policy on online behavior.

“I might ‘know’ what the policy is but I do not see it being enforced,” one person answered.

“I know what is expected, but I see many apparent violations of people’s use of computers for personal use,” a survey taker said. “However, I think the agency is at fault for allowing certain sites to be accessed.”

According to the survey, the areas where offices and agencies need the most help are understanding how to mitigate cyber risks and balancing mission needs with cybersecurity needs.

When asked whether their agency or office has made changes to its cybersecurity as a result of the OPM breach, about 48 percent of those working within 50 miles of Washington said yes, while only 30 percent of those who lived outside that radius said yes.

About 30 percent of respondents who lived outside the District disagreed that their office had made changes, while 41 percent were unsure.

About a quarter each of respondents who live inside the Beltway said they either disagreed or were not sure if their workplaces had made changes as a result of the breach.

“Maybe not so much to infrastructure but on end-user training and awareness. Every time your computer reboots a big notice comes up reminding you to be safe online,” said one respondent.

“My agency has always been concerned with cybersecurity, but aging systems and low budget have an impact,” another wrote.

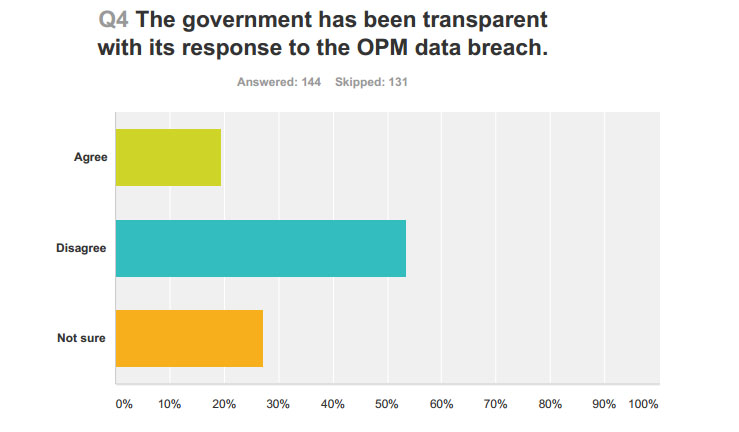

A combined average of 57 percent of the employees inside and outside the D.C. area say they did not believe the government was transparent in its responses to the OPM data breach. Only 14 percent said the government had been transparent, while an average of 29 percent said they were not sure.

“The congressional and OPM responses have both left me confused,” a large civilian agency employee said. “The funding OPM has requested to upgrade its IT infrastructure is far too low to effectively address the problem. Congress doesn’t seem to want to help and isn’t insisting on a realistic figure.”

“All I got was a letter in the mail and an email saying we were breached,” said a respondent from a large agency. “I was on my own to figure out how I was affected.”

Jim Jones, associate professor of computer forensics at George Mason University, said the lesson to take from OPM is “monitor, monitor, monitor.”

“It’s when they put monitors on the network, they saw evidence of the attack, it wasn’t anything super sneaky by the time they found it,” Jones said. “Had they been watching more closely, sooner, they would have seen it. So a valuable lesson was learned at great expense and pain. I think everybody out in the field took that lesson to heart.”

Read all of Federal News Radio’s Special Report: The OPM Breach: What’s Different Now.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Related Stories