Historic absences at MSPB hit 4-year mark, creating potentially costly backlog

The Merit Systems Protection Board marked four straight years this month without a quorum. While some are hopeful the incoming administration will quickly name new...

Another year, another milestone for the Merit Systems Protection Board.

The board has been without a quorum since January 2017, fours years that encompass the entirety of the Trump administration, and it hasn’t had a single member for nearly two years.

The holdover term for Mark Robbins, the last remaining MSBP member, expired back in March 2019. The Senate hasn’t confirmed any of President Donald Trump’s nominees to fill the board in recent years, sparking a debate over who’s to blame for the historic absences at the MSPB.

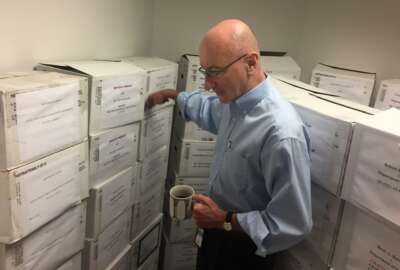

Those absences have created an equally historic backlog of 3,071 pending petitions for review (PFRs), according to MSPB data as of the end of December.

For the employees and senior executives who have spent years waiting for the board to take action on their cases, a vacant or inoperable board has personal costs.

But it also has financial costs for agencies, which, whenever a quorum is restored and new board members begin issuing final decisions, may have to dole out tens of millions of dollars in back pay to employees who were wrongly terminated and have waited the last four years for their reinstatements.

“Not having a board hurts both sides,” said Bill Wiley, a federal employment attorney and former counsel for the MSPB. “[For] the appellants who were fired who should not have been, many of them are sitting out there without a paycheck, so they’re suffering. Agency backpay is accumulating every day that [members] don’t issue a decision, if they’re going to get backpay. It’s one of the rare things that you can screw up in government that really hurts both sides of the equation.”

Out of roughly 3,000 pending petitions for review, Wiley estimates about 10%, or 300, are cases that involve an employee who was wrongly removed and is owed back pay.

Some of those cases have been pending for four years and possibly longer. But using a median wait time of two years, and a rough annual salary of $100,000 for each of those 300 former federal employees, Wiley said agencies could owe at least $60 million worth of back pay, a number that has only grown as more cases pile up and the parties wait longer for a decision.

That estimate doesn’t account for attorneys’ fees, or higher salaries for members of the Senior Executive Service who may have cases pending before the board. Salaries for the SES in 2021 range between $132,552 and $199,300, according to the Office of Personnel Management .

“When it comes to government, it’s pennies,” Wiley said. “The money is something everybody can understand. For those of us who know the civil service, it’s the internal disruption, the pain for these employees who shouldn’t have been fired who were fired, and the pain for the managers that four years after they fire somebody are going to have to say, ‘Good morning, here’s your desk.'”

How long will it take to resolve the MSPB backlog?

Federal employment attorneys, as well as employee groups and unions, are hopeful the days of an empty board are numbered.

They’re counting on the incoming Biden administration to name new members — two Democrats and one Republican as is customary — to the board. And they’re counting on the Democratically-controlled Senate to quickly confirm those members so the MSPB can be functional again.

The MSPB, of course, has continued to operate without a quorum during the last four years. Administrative judges have continued to hear appeals and issue initial decisions. MSPB attorneys have continued to review and draft decisions on the pending petitions for review as if board members were present during the last four years.

The work that the career MSPB staff has done to prepare those draft decisions will be critical for new members as they attempt to work down the backlog.

“It’ll be a matter of the board members trusting the career staff, and that trust might have to happen faster than normal times for the sake of getting decisions out,” said Jim Eisenmann, a former MSPB executive director and general counsel and now a partner with Alden Law Group.

“Obviously something needs to be done to move things faster than they normally would,” he added.

New board members could issue short-form decisions, which would simply inform agencies and employees of the board’s final decision without the usual analysis and recap of the arguments that a longer order might have. Eisenmann said the MSPB once issued short-form final orders on non-precedential cases for a period of time.

“There are probably plenty of what would be called easy cases to apply that to,” he said. “Some PFRs are untimely, or there’s clearly no jurisdiction. You could get those orders out faster than you ordinarily would using those non-precedential final orders.”

In the past, the board usually voted on cases on a “first in, first out” basis, meaning members issued final decisions on the oldest petitions first, Wiley said. But a new MSPB chairman may choose to approach the backlog in a different manner.

A new chairman could, for example, choose to consider all removal or whistleblower cases first.

“They have a lot of things they could do,” Wiley said. “[For] the new board members, that’s the first major decision that the chairman is going to have to make: what order of attack will they engage in for these pending 3,000-plus cases?”

Wiley said the board members he worked with during his tenure could vote out four or five decisions a day, a daily workload that allowed the MSPB to keep pace with the usual influx of cases moving in and out of the agency.

But with a backlog of more than 3,000 cases, the new board members will have to “shift into a separate gear,” he said.

Assuming new board members trust the work the MSPB career employees have done to prepare the cases, Wiley said the appointees could potentially move through dozens of cases daily — as long as they’re relatively simple ones.

“They could have voted 50 cases a day,” Wiley said, thinking back to the board members he worked for during the Reagan and Clinton administrations. “Now that’s busy. They’re not going out for two-hour lunch breaks.”

But the vast majority of cases that come before them are relatively straight-forward, Wiley said. He envisioned a scenario where new board members could could move 200 cases a week and bring the backlog to a more manageable level in six-to-eight months.

“Most cases are relatively routine in that the case law is well-established. It’s an application of the facts … and most of the time the board members agreed on the results,” Eisenmann said. “It’s a matter of the board members obviously, conscientiously reviewing the recommended decisions, maybe having discussions with their chief counsels and then getting the decision out the door. Ordinarily things move relatively quickly.”

Eisenmann was more conservative in his outlook for the board and the backlog. He said it could be years before the board addresses the backlog, though he will recommend his clients use the MSPB to file petitions once it’s fully functional again.

Like other federal employment attorneys, Eisenmann said he’s recommended clients appeal to the Federal Circuit while the MSPB has been without a quorum. But not everyone can afford it.

“They don’t have the money … or the resources to go to the Federal Circuit. That’s a shame, number one, that the option is taken from them, and number two, that they’re going to have to wait a really long time to get a decision,” he said. “It’s more than unfortunate. To me, it’s a delayed justice for everyone involved, particularly the individuals.”

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Nicole Ogrysko is a reporter for Federal News Network focusing on the federal workforce and federal pay and benefits.

Follow @nogryskoWFED

Related Stories