Exclusive

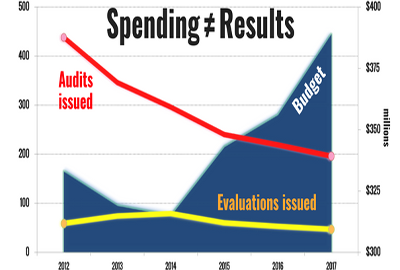

Why does HHS OIG’s budget keep rising as its output keeps falling?

The Office of Inspector General at Health and Human Services has been spending more money and achieving less results for years, according to publicly available...

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

The Office of Inspector General at Health and Human Services has been spending more money and achieving fewer results for years. And it’s not clear whether anyone is paying attention or even cares to hold the office accountable.

Data taken from the HHS OIG’s reports to Congress from 2014-2019 and President’s Budget Requests from the same years show the audit agency’s budget has trended upward since 2012, increasing by 16 percent. Meanwhile, the IG office’s returns on investment (ROI), the numbers of audits and evaluations issued, and the number of investigations started and completed have gone down over the same time frame. And a recently retired HHS OIG analyst, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retribution, said certain personnel decisions have exacerbated the issue.

“They keep all this management fluff. You don’t need anywhere near that management structure. Oh my God. They just keep hiring more of it.”

— former HHS OIG analyst

During a time of constricted budgets, a push by the Trump administration and Congress to get more value out of every dollar spent, it’s unclear why the HHS OIG returns and productivity are dropping as Congress invests increasing amounts into the office.

Either the OIG is attempting a long-term pivot that hasn’t yet paid dividends, or the problem is mismanagement, said one former deputy IG, who spoke on condition of anonymity in order to preserve relationships within the IG community.

“What is it they’re trying to accomplish? Are they refocusing for a purpose, or is this just how they think they ought to be managing?” asked the former deputy IG. “And if this is how they think they ought to be managing, then they ought to be held to account for these numbers.”

And that’s part of the problem: it’s unclear who is watching the watchers.

Neither the House nor the Senate’s Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies subcommittees, responsible for HHS appropriations, immediately responded to requests for comment. The office of Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) expressed interest in the situation, but offered no insight.

HHS OIG declined an interview for this story, instead offering the following statement:

“As the largest civilian Office of Inspector General in the federal government, we are responsible for oversight of the Department of Health and Human Services’ more than $1 trillion portfolio of programs. Key to the agency’s efforts are our use of data analytics and multidisciplinary state-of-the-art investigative techniques to detect crime and conduct criminal investigations of fraud. The 2018 National Health Care Fraud Takedown demonstrates the impactful results of employing such tactics and techniques. We have made significant progress in our fight against health care fraud, waste and abuse, and we remain committed to protecting the health and welfare of millions of Americans.”

HHS OIG’s budget

In fiscal 2012, HHS OIG had a budget of $323 million. That dropped to $319 million in 2013, and again to $315 million in 2014. Since then, however, its budget has steadily risen to $389 million in 2017.

And those numbers are expected to increase to $420 million in 2019, up from an estimated $407 million in 2018.

Of the money devoted to oversight — the vast majority of the OIG’s budget — anywhere from 75 percent to 85 percent is specifically dedicated to the Healthcare Fraud and Abuse Control (HCFAC) program, according to agency budget justifications. This money can come from multiple places, the former HHS OIG analyst said, including a trust fund and specific allocations from Congress. The rest goes to oversight of public HHS programs.

Meanwhile, the yearly budget justifications show both measures of ROI have fallen since 2014.

HHS OIG’s returns

The HCFAC ROI peaked in 2014 at $8 recovered for every $1 spent, and has since fallen to $5:1 in 2017. The overall HHS OIG fraud and abuse ROI, which lumps the HCFAC ROI in with the rest of HHS OIG’s oversight efforts, similarly peaked in 2014 at $18.60:1, but has since fallen to $14:1.

Further, HHS OIG said the HCFAC program returned “more than $4” for every dollar spent in its 2018 National Health Care Fraud Takedown. That’s down from $5:1 in 2017; despite the OIG’s characterization of “significant progress,” the ROI continues to drop.

And although it receives 75 percent to 85 percent of the OIG’s funding, HCFAC consistently accounts for less than 50 percent of the money HHS OIG recovers.

“If you compare those numbers, despite the fact that the HCFAC is getting three-quarters of the budget, it’s not as high of a return on any investment as the rest of the things the OIG is doing,” the former HHS OIG analyst said.

“They don’t want to approve anything that would be risky … so the only safe thing to do is to keep saying, I think I want to see it one more time. Just one more time.”

— former HHS OIG analyst

For context, the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency (CIGIE) publishes an Annual Report to the President and Congress, which includes the average ROIs for OIGs across government, which between 2012 and 2016 — the last year for which this data is available — varied between $14:1 to $21:1. The Government Accountability Office also publishes its ROI each year, which between 2012 and 2017 varied between $100:1 to $134:1.

However, these comparisons are not apples-to-apples. GAO is responsible for oversight of the entire federal government. And HHS OIG is unique among OIGs in that it is required to oversee Medicare and Medicaid, among other large public welfare programs.

Of course, not all results of an OIG investigation, audit or evaluation can be quantified monetarily.

“The return on investment relates to the dollars recovered,” the retired HHS OIG analyst said. “There are other things that can come out of an audit or evaluation. This is probably even more valid for evaluations. If Congress ends up changing [a] law because of the reports that are issued, that doesn’t always get quantified in dollars, but it can make a big difference in the program. And some of the biggest things that can be done may do things like save lives, make people live longer.”

The HHS OIG, however, doesn’t publicize those kinds of results. They’d be hard to track and even harder to quantify, the retired HHS OIG analyst said. So the only way to judge performance is through publicly available data.

“This is what they put forward,” the retired HHS OIG analyst said. “If there are other important things then they ought to be putting it out there.”

HHS OIG productivity

Just as there are types of returns other than monetary, there are metrics of performance other than ROI. Taking a look at the number of audits, evaluations and investigations performed by the OIG can indicate the efficiency and effectiveness of the office as well.

Here, the results are less cut-and-dried. HHS OIG has issued fewer audits every year since 2012, and fewer evaluations every year since 2014.

Of course, less quantity does not necessarily equal less quality. In fact, the former auditor said the smaller number of audits was by design.

“In the beginning part of that slide [Deputy Inspector General] Joanne Chiedi was telling [the Audit division] ‘I want fewer audits,’” the former analyst said. “But what she was saying is ‘I want fewer, larger audits,’ and there would be nothing wrong with doing fewer audits that resulted in larger recommendations for dollar recoveries.”

Chiedi became principal deputy IG at HHS OIG in 2013.

But if the HHS OIG was targeting bigger audits with greater returns rather than a higher number of smaller audits, the returns on investment would not have suffered so greatly, the retired HHS OIG analyst said. At least, not if they were successful.

The percentage of audits issued within one year has also dropped steadily since 2012. However, the percentage of evaluations issued within one year has ticked back up since 2015, rising from 56 to 64 percent.

And finally, the numbers of investigations both opened and closed are a mixed bag as well. Both numbers have trended downward since 2012, though the number of investigations began to tick back upward in 2015. The number of investigations closed followed suit in 2016.

Both the former deputy IG and the retired analyst said this uptick could mean the Office of Investigations has turned a corner. It remains to be seen whether these downward trends will be reversed. But the graph also shows clear fluctuations in these numbers over the five-year period. If the upward turn proves to be temporary, this could just be another example of those fluctuations. It’s impossible to determine either way without another year or two of data, they said.

SES expansion

One other thing has trended upward since 2012 alongside HHS OIG’s budget: its number of managers. The number of members of the Senior Executive Service (SES) within the office has risen by half since 2012, and the number of senior leaders — who don’t have to be approved by the senior executive board — has risen from one to six in the same period.

Meanwhile, the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) staff members that aren’t management fell by more than 10 percent between 2012 and 2017, according to data from the budget justifications.

That’s lowered the ratio of 3.8 employees to every manager down to 3.1 employees per manager. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but the experts say it raises questions.

“If they’re bringing technical expertise in, it’s going to be a very small staff, and that’s going to kill your ratio,” the former deputy IG said. “And it may be for a good purpose. But those strategies ought to be apparent to everyone. What is the strategy? Has it changed, what’s the focus?”

For example, bringing in money-laundering experts or cybersecurity experts to chase hidden fraudulent Medicare or Medicaid funds requires a higher rate of pay in order to compete with the private sector. That could explain the increase in senior leader positions. They would also require smaller staffs, as they aren’t involved in administration, the former deputy IG said.

But it’s not clear whether this is what happened, as the 2014-2018 strategic plan on HHS OIG’s website makes no mention of any such pivots or refocusing of priorities, nor do the budget justifications. It does mention building on the Medicare Fraud Strike Force Teams, which Federal News Radio reported on in 2015 and 2016, but again, if this program has been so successful, why have ROIs dropped?

The former HHS OIG analyst said the senior leader positions in question largely went to attorneys and medical experts involved in administration, not technical functions.

The former HHS OIG analyst also said the staff situation stemmed from incorrect assumptions about hiring and promotions. HHS OIG budget justifications from 2012 and 2013 noted that increases in hiring in previous years yielded improved returns, and the office intended to continue scaling up in order to expand oversight of Medicare, Medicaid and other public HHS programs.

However, sequestration took effect, and the sequestration operating plan HHS OIG published details the budget cuts the office suffered in 2013. That’s also when the number of full time staff began to drop.

“I think the problem is that we hired and promoted into the upper supervisory levels assuming that we were going to grow even three or four years ago,” the former HHS OIG analyst said. “We had insane assumptions that we were going to grow to a very large level and then it didn’t materialize. We never grew that much and now we’re being asked to cut back. And of course, what did they cut? They cut the staff positions and they keep all this management fluff. You don’t need anywhere near that management structure. Oh my God. They just keep hiring more of it. That’s what makes no sense. Even after it was clear we weren’t going to grow. They keep hiring managers and you can’t tell what they think they’re going to manage.”

And that’s led to a situation of too many managers, not enough employees, the former analyst said. Each senior leader, the auditor said, felt like they needed a staff of GS-13s, -14s and -15s. But their duties aren’t always coherent or complete, leaving some in a position where they feel they need to justify their own existence.

“So they all start demanding lots of briefings and they start reviewing everything but they don’t want to approve anything that would be risky and they don’t want to deny anything that would be risky,” the former analyst said. “So the only safe thing to do is to keep saying, I think I want to see it one more time. Just one more time.”

Audit reports now are reviewed five different times during the audit cycle, the former analyst said, whereas they used to be reviewed only twice during the draft stage and once at the final stage.

Other types of reports are being reviewed seven, even 11 times. This bureaucratic micromanagement is pumping the brakes on HHS OIG’s output, the former analyst said.

“They work for a woman who doesn’t hesitate to chop off heads,” the former analyst said, referring to Chiedi. “So they start looking for ‘how can I look like I’m doing something even though I’m not doing something.’”

Federal News Radio repeatedly offered HHS OIG the opportunity to share its side of the story, and specifically requested an interview with Chiedi, but the OIG public affairs staff declined.

If this were any other office within HHS, the OIG would be the one investigating to find out why output is dropping, what the extra budget money is being spent on, and how to get the office back on the right track.

“Offices of Inspector General play a key role in rooting out waste, fraud and abuse in the federal government,” Grassley said in an emailed statement. “These watchdogs should be properly funded, but taxpayers also deserve to know that their hard-earned dollars are being well-spent.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Daisy Thornton is Federal News Network’s digital managing editor. In addition to her editing responsibilities, she covers federal management, workforce and technology issues. She is also the commentary editor; email her your letters to the editor and pitches for contributed bylines.

Follow @dthorntonWFED