Reskilling and upskilling offer opportunities and challenges for agencies and employees

This column was originally published on Jeff Neal’s blog, ChiefHRO.com, and was republished here with permission from the author. We have heard a lot recently...

This column was originally published on Jeff Neal’s blog, ChiefHRO.com, and was republished here with permission from the author.

We have heard a lot recently about reskilling, upskilling, and other terms that generally mean retraining workers to function in a changing workplace. The CIO Council deployed a Federal Cybersecurity Reskilling Academy pilot that proved successful enough to refine and continue. The Office of Personnel Management issued a suite of tools under the umbrella of “Accelerating the Gears of Transformation.” OPM’s tools include an Executive Playbook for Workforce Reshaping, a Reskilling Toolkit for HR and managers, and Guidance for Change Management in the Federal Workforce. Most recently, the Partnership for Public Service released a report, Looking Inward for Talent, that advocates for greater use of reskilling as a means of delivering the talent the government needs.

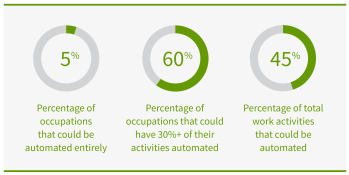

OPM’s 2018 Federal Workforce Priorities Report highlighted the potential disruption of the workforce due to increased automation. They reported that 60% of jobs could have 30% of more of their activities automated. Although such changes are not going to happen immediately, they point to an increasing problem for the federal workforce and the workers everywhere. More and more jobs will be automated, skill requirements will change, and the pool of available talent may not have all of the skills needed to perform the work. The global scope of the issue means agencies will be joining the private sector in a search for talent that simply may not be there. Competitive pay, benefits and working conditions will not guarantee that the government or any private sector employer will be able to hire the people they need.

highlighted the potential disruption of the workforce due to increased automation. They reported that 60% of jobs could have 30% of more of their activities automated. Although such changes are not going to happen immediately, they point to an increasing problem for the federal workforce and the workers everywhere. More and more jobs will be automated, skill requirements will change, and the pool of available talent may not have all of the skills needed to perform the work. The global scope of the issue means agencies will be joining the private sector in a search for talent that simply may not be there. Competitive pay, benefits and working conditions will not guarantee that the government or any private sector employer will be able to hire the people they need.

At the same time, workers are staying on the job longer. Many people do not want to stop working as soon as they are eligible to retire. Whether it is because they need the money, enjoy the challenge, or just want to get out of the house, we are seeing retirement ages creeping up and seeing older people returning to the workforce. The problem is that many of the existing or returning workers have skills that do not entirely match what agencies and private sector employers need.

There is much that agencies can and should do to cope with changes that artificial intelligence and greater automation will bring. I plan to address those in the third part of a series that began with my post Artificial Intelligence is More than a Tool, It May be Your Replacement, and continued with my post From Human Resources to Helpful Robot – How AI May Transform HR. If that were all agencies had to contend with, it would still be a major challenge. The problem is that it is not all they are facing.

That aging workforce that is staying around for more years is still aging, and eventually they will go away. The government is not hiring young people, and the competition for both skilled and unskilled workers is fierce in many job markets. Highly skilled occupations are in high demand in most areas where there are large concentrations of federal workers. Some, such as medical professionals, are in high demand everywhere. When we think of reskilling in government, the focus is typically on skills such as cybersecurity. I believe agencies are going to find that it is far more than those specialized jobs that they will have to worry about.

Hiring and training entry level employees is something virtually every employer does. It is a standard practice that is the way many federal workers get started. What may need to happen now is the establishment of more avenues for entering those jobs. The CIO Council’s Cybersecurity Reskilling Academy is a good example of taking people who are not in an occupation and providing them with a subset of skills that can help agencies meet specific requirements. The graduates of that program did not become instant cybersecurity experts, but they did develop useful skills. Other programs could take skilled workers and provide even more specialized skills.

Another alternative that we do not see often is establishment of sub-entry level positions. For example, most two-grade interval jobs have a GS-5 or GS-7 entry level. Agencies looking to fill those jobs typically look for people with a bachelor’s or master’s degree. At the same time, there are people in other positions who could be retrained to do the work, but who do not have the desired degree. There are also veterans who come out of the military without skills that are directly marketable. For example, someone who enlists in the Army, goes into the Infantry, and leaves after one enlistment, will have a lot of characteristics that should be desirable to employers. But — they are not likely to have the degree or the directly applicable experience that employers are seeking for entry level jobs. The result is that young veterans tend to have high unemployment rates.

Why not create positions below the entry level that would enable bright people without the required qualifications to be hired, trained, and prepared for those entry level positions? Such programs could also be used to totally reskill current employees whose skills no longer match agency needs. The government has done that before with upward mobility programs.

There are a few issues that are likely to get in the way. Managers usually want fully skilled employees. That is even more true if they have had staff reductions and need every skilled person they can get. HR offices are not always the most flexible parts of an organization, and they tend to want to do what they have always done. That means filling jobs at the entry level, full performance level, or somewhere in between. The idea of hiring someone at the GS-4 level for a job that has always been a GS-5/7/9/11/12 does not sit well with them. The HR system itself is not designed for much flexibility, although agencies have many options that they do not use. Employees also present some problems. Employees in GS-11 jobs that are going away are often not willing to accept a GS-5 position that would get them back to their current grade level in a few years, even with grade or pay retention.

To make reskilling and upskilling work, agencies and their employees, managers and HR staff will have to be willing to change how they do business. The demand for talent and the aging workforce will make that a necessity.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.