Exclusive

Exclusive Exclusive

Peering into the black box of OTA awards

Information about Other Transaction Agreements is so hazy that no one is quite sure of the total dollar amount DoD has spent on OTAs over the past three years.

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

The waters surrounding the Defense Department’s new favorite way to buy and develop systems are murky.

In the past three years, DoD awarded nearly $21 billion in Other Transaction Authority (OTA) agreements — using the approach to fund prototypes and production for night vision goggles, parachutes that can carry more weight, miniature satellites and a host of other ideas.

But finding out exactly who that money goes to, how it’s spent, the parameters dictating a “contract” and what actually needs to be delivered to the military is nearly impossible.

In fact, information about OTAs is so hazy that no one is quite sure of the total dollar amount the department has spent on OTAs over the past three years, in an era when Congress has significantly expanded the military’s authority to use the acquisition shortcut.

The official answer, according to the Pentagon’s public affairs office, is $21 billion between 2015 and 2017. But the authoritative federal spending database, the Federal Procurement Data System — relied upon by lawmakers, industry groups and watchdog organizations — yields a much lower number for the same years: $4.2 billion.

That fundamental discrepancy is just one example of the information gaps Federal News Radio found in part two of its exclusive special report, Danger at High Speed: The Fog Around OTAs.

The precise reasons for why DoD’s self-reported figures vary so drastically from the government’s databases are unclear. But they likely have something to do with the fact that OTAs, by design, bypass almost every rule in the federal procurement system in the name of speed and innovation.

“One of the main concerns is these types of agreements don’t operate under the Federal Acquisition Regulation,” said Scott Amey, general counsel for the Project on Government Oversight. “That always creates some problems and it creates a risk that we’re going to be subject to waste, fraud and abuse when this contracting vehicle is used.”

Angela Styles, a former administrator for the Office of Federal Procurement Policy and current partner at Bracewell, echoed Amey’s concerns.

“There are a lot of risks to having no rules. There are no rules for competition. There are no protests. None of the things you would consider just a regular day-to-day oversight of them. There’s nothing that really says they have to be reported, other than what may be in the statute for reporting them,” she said. “There’s nobody who knows how to manage them and there’s nobody who knows what the terms and conditions should be. It’s a completely unknown world, but with the benefit of allowing easier access to products and services for the Department of Defense.”

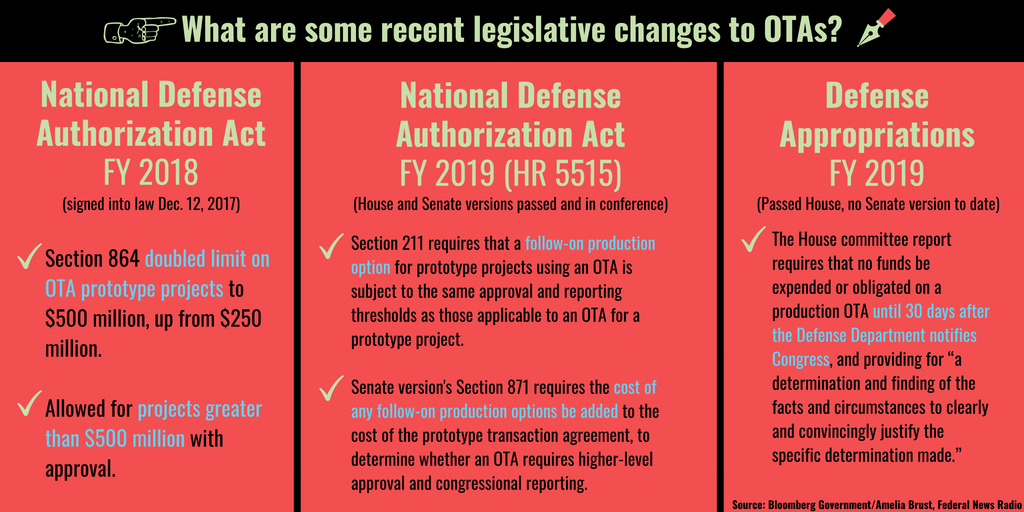

Despite the lack of transparency, Congress continues to expand OTA authority for the Pentagon.

A small number of agencies, such as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the Missile Defense Agency, previously used the agreements purely for prototypes. But now, OTAs are open to the military as a whole, can be used for follow-on, full-rate production agreements and there is no limit on the size of the deals.

Even considering the risks, acquisition officials and industry advocates are pressing forward with OTAs and are reluctant to add too many oversight measures.

“This mechanism is just so much faster and so much more attuned to getting something quickly that we want today and not have to spend a couple years going through a protest, going through this huge process to get something we wanted two years ago,” Air Force Director of IT Acquisition Process Development Maj. Gen. Sarah Zabel said last fall. “Everyone is very enthusiastic about OTAs.

The anatomy of an OTA

Congress created OTAs to bring together nontraditional companies with new technologies to the government. Congress hoped that by shoving off all the regulatory barriers to working with the government, the Pentagon would attract businesses that were not interested in working with DoD or were too small to deal with the red tape of the federal acquisition process.

OTAs can be awarded to just about anyone, as reported in part one of our exclusive special report Danger at High Speed: OTAs in Action, but one of the most popular ways is through consortia made up of companies specializing in one field.

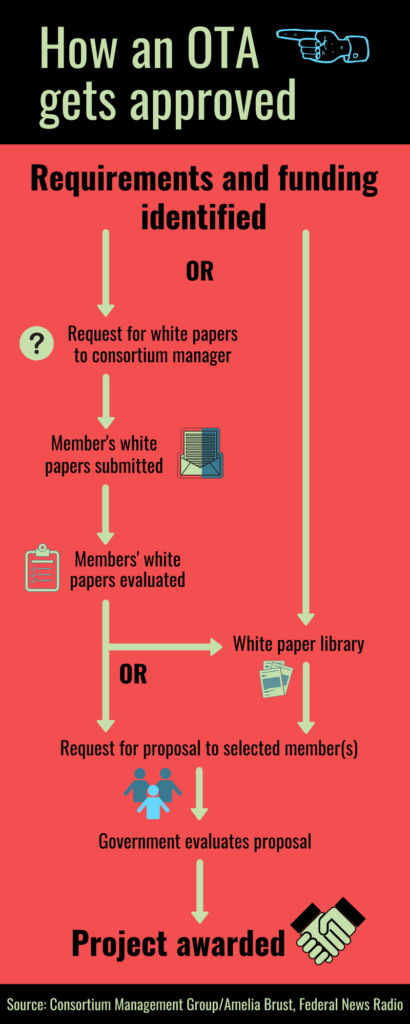

DoD will sign an agreement with a consortium and then call on the consortium when it has a need.

“The consortium gives you the ability to go execute orders. You have some program out there and they are having trouble with some piece of technology that’s not working. You can quickly get into the consortium, ask them for ideas on how to solve that. But the other thing the consortium really does if you set this up right, is that you can encourage unsolicited suggestions for technology advancements and research, because you don’t always know what you don’t know,” said Bill Deligne, deputy executive director of Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command Systems Center-Atlantic.

Companies go through an extremely truncated process to submit their proposals and DoD moves to an award.

In other cases, DoD will work directly with a company. The Defense Innovation Unit Experimental, for example, awards OTAs to firms without using a consortium as an intermediary.

Both government and industry see OTAs as a way DoD can keep up with near-peer competitors like China and Russia, which do not have an acquisition process with as much oversight, or a culture based on building large, exquisite weapons systems.

Professional Services Council CEO David Berteau said so much innovation has been coming from outside the government that OTAs are a great way for DoD to bring in new technologies and ideas from companies that usually don’t do business with the Pentagon.

Transparency issues

Beyond the optimism, information regarding OTA agreements is hard to come by.

Currently, Congress only requires the department to provide lawmakers with formal notification when DoD signs an OTA for more than $500 million. In that case, the DoD acquisition chief must also determine in writing that the requirements of OTAs are met and the OTA is essential to critical national security objectives.

Those congressional requirements include that at least one “nontraditional defense contractor or nonprofit research institution” participates in the prototyping to a “significant extent.” That requirement can be sidestepped if one-third of the total cost of the prototype comes from a source other than the government. And DoD can bypass both of those rules if a service acquisition executive makes a determination that “exceptional circumstances” justify the use of OTAs for “executing innovative business models.”

The law does not define what a “significant extent” entails. It also doesn’t define what constitutes a prototype.

One industry expert who works with consortia said in his experience a “significant extent” can be just 25 percent of the work or funding, or if a nontraditional owns a technology that is imperative to the project.

Robert Levinson, senior defense policy analyst at Bloomberg added, “I think there are a number of definitional issues within the OTA statutes that are probably going to be evolving as people come to understand. I think production is another one. What does ‘production’ mean?”

Since they are not contracts, OTAs, by definition, are exempt from many laws Congress enacted over the years to protect the integrity of the procurement system.

OTAs do not have to abide by:

- the Procurement Integrity Act, which prohibits acquisition officials from taking gifts from companies;

- the Drug Free Workplace Act, which requires federal contractors to provide a drug-free workplace as a precondition to a contract;

- the Competition in Contracting Act, which requires full and open competition for contracts valued more than $25,000; and

- the Contract Disputes Act, which handles claims of misuse against companies and the government.

Those are only a handful of the laws that do not apply.

OTAs start at ground zero and then build a contract from the bottom up, said a former congressional aide, who played a key role in drafting many of the congressional directives on the use of OTAs.

“To what extent can you give the contractor direction? To what extent can you make changes? What do you have to go through to do that? How much do you have to compensate the contractor when you do that? How do you resolve disputes? Who has the rights to the technical data when you’re done? Does the government get the rights to the project since they paid for it or does the contractor? What’s within the scope of the contract and what isn’t within the scope of the contract? How much can you expand or not expand it? How do you ensure that you’re fair to the participant or how do you how do you ensure that you’re fair to other people? Those are all the things that the contracting system has a set of rules to address,” said the former aide, who requested anonymity because of their current ties to the Pentagon.

OTAs do not address any of those questions up front.

If the government and contractors forget to close every single loophole as they build the agreement, then things can get messy.

“You’ve got to address every issue upfront as a first impression issue or else you accidentally leave some of these issues out and don’t address them. And so you don’t protect either the contractor or the government on some important issue. That leads to disputes down the road or you don’t provide for fairness to people. These are the kinds of things that can come back and bite you with an OTA and end up being more work,” the former congressional aide who worked on OTA legislation said.

The agreements the government and industry enter into are, in almost every case, kept from the public.

“DoD is pretty much regulating itself at this point. Eventually there are going to be reviews, whether they are Government Accountability Office or IG reviews, and people will figure out whether this is working. Internally, within DoD, you would hope that people who are using these things regularly would review what they’re doing,” the former aide said.

Acquisition officials say they understand the responsibility placed on them with OTA oversight, and the risk that Congress might rein-in the authorities if someone messes up.

“Everybody knows that there are always going to be people who take advantage — one way or another — of rules, which is why the amount of statute, the amount of regulation and the amount of policies that cover the acquisition business are ginormous,” Lt. Gen. Paul Ostrowski, the director of the Army Acquisition Corps told the Association of the U.S. Army at a conference earlier this month. “We have to protect this tool. This is a gift on behalf of the Congress of the United States of America to the Department of Defense saying ‘We trust you to get after this thing, to be more rapid, to be more agile. Don’t screw this up.’ And guess what? We’ve done that. We’ve screwed this up. There are a couple of examples out there.”

One of the most recent examples involved a nearly $1 billion OTA between the Defense Innovation Unit Experimental and REAN for cloud services.

“It was really the lack of transparency that was the problem there,” said Tim Greef, founder and CEO of the National Security Technology Accelerator, a consortia management firm. “The fact that no one really knew it was happening and then it became this big thing that spiraled out of control.”

Greef said some congressional staff members found out about the REAN contract through the media, despite the law requiring congressional notification of OTAs $500 million or more.

Pentagon officials stepped in at the last minute to tamp down the agreement to just $65 million, and the Government Accountability Office later ruled that DoD overstepped its legal authority altogether when it awarded REAN a follow-on production contract before determining whether the company’s initial prototype met the government’s needs.

Scavenger hunt

While determining the total number of dollars DoD spends on OTAs is difficult, figuring out where the money goes is even harder.

If DoD works with a consortium, transparency is based on the consortium’s rules and any parameters it worked out with the Pentagon.

In some consortia, the department awards OTA funding directly to the consortium itself, not to member companies, and the consortium does not report which companies performed the work. If two companies partner up on a project, there are rarely any details on who did the most work or who received the most funds.

Some consortia, however, make it a point to be transparent.

“We think if you use preset transparency on the front end then you won’t really have any complaints on the back end,” Greef said. “We come at this engagement as truly a public-private partnership … Anything that the government is posting, we post.”

Of course, not all consortia operate as openly. POGO’s Amey worried DoD may repeat the past and end up in an agreement that wastes money and pads corporations’ profits.

“We’ve already seen [waste, fraud and abuse] in the Future Combat Systems,” Amey said referencing an Army program that partly used OTAs in the mid-2000s. ”There were a lot of inquiries into that project and the program was canceled in 2009. You do worry about the costs and the cancellation fees that will go along with that. That was the poster example for a program that wasn’t run very well. As we move forward, we need to make sure there’s proper oversight over these programs to make sure that we’re getting the bang for the buck that we need and that these programs are not just promises … and at the end, you don’t end up with a huge waste of money.”

Aging OTAs

Seventy percent of a program’s cost is in sustainment. OTAs’ use of nontraditional companies and unconventional agreements leave some experts wondering how DoD will sustain systems in the future.

“There’s nothing inside of OTA today that requires the government to think about that life cycle sustainment and what’s the cost and structure to sustain that over time,” PSC’s Berteau said. “Before you move from prototype into production, there needs to be a set of questions that asks ‘Who will support this? Who’s going to sustain this?’ You can get a great idea upfront that really works well, but if you can’t sustain it over time, it’s not really worth it to you.”

If DoD awards a contract to a small, nontraditional business, but that business isn’t around in five years to supply extra parts or maintenance for that project, how will the Pentagon keep it working?

Analysts wonder how much it will cost DoD to replicate those parts or to buy the intellectual property rights from a company that may not even exist anymore.

“If 70 percent of your costs are in the lifecycle support and you’re not considering that as part of the upfront analysis and evaluation, then you could be setting yourself up for some real big downstream costs without knowing it,” Berteau said.

Repeating DoD history?

While DoD is excited about the potential to award funds quickly in order to operate in the new threat landscape laid out in the National Defense Strategy, the department has tried this tactic before and gotten its hand slapped.

In the 1990s, DoD expanded the use of OTAs on a temporary basis for basic, applied and advanced research projects. DARPA also gained the ability to enter into OTAs for prototype projects that were directly relevant to weapons under development.

Those rules were significantly stricter than the current law, which is open to all of DoD and allows for follow-on production contracts.

Back then, DoD wanted to engage with nontraditional companies. But what it got was faster awards for old guard Defense companies.

By the mid-2000s, Congress started noticing something wasn’t right with OTAs.

“In short, though the freedoms associated with OTA may attract more businesses to participate, they also carry significant risks for the federal government. While we all want technology faster and cheaper, we also have to be mindful that we are stewards of American tax dollars. If we are going to allow this kind of flexibility at the department, the department must demonstrate to this committee that it can be trusted to handle the authority. This means showing that adequate protections are in place to reduce or eliminate any potential abuses of OTA,” Rep. Jim Langevin (D-R.I.), said during a 2008 hearing of the Homeland Security Subcommittee on Emerging Threats, Cybersecurity and Science and Technology.

The DoD Inspector General’s office found of the OTAs awarded in the late 1990s, 72 percent of research funds and 97 percent of prototype funds went to traditional contractors.

“We are hearing a new explanation for OTA, that the primary benefit to contractors is that they can fully protect their intellectual property rights. In addition to the elimination of contracting controls, the companies that enter into OTA agreements retain their ability to make a dollar from the programs that were funded by Uncle Sam,” said POGO’s executive director Danielle Brian during a 2005 hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee.

The former congressional staff member who worked on OTA legislation agreed that the vast majority of dollars went to traditional contractors. That’s why the rules were tightened until 2015 when Congress loosened the reins again.

A 1998 DoD IG report recommended better monitoring of the actual costs of OTAs.

The IG expressed concerns about how those problems might compound themselves if OTAs were allowed to expand into agreements that extended beyond small prototypes.

“Given the inapplicability of traditional controls to ‘Other Transactions,’ we believe that if this authority is extended to billion dollar production runs of equipment, additional scrutiny of pricing for sole-source items will be needed to protect DoD and taxpayer interests. In these cases, the department should require access to cost or pricing data, plus audit access for the Defense Contract Audit Agency, in order to ensure fair prices,” the report states.

Government watchdog groups said there is reason to question whether DoD is keeping an eye on its current OTAs and subjecting them to internal monitoring and oversight, since DoD never heeded the IG’s recommendations 20 years ago.

“I’m always afraid we’re using [OTAs] for the wrong purposes … with the lack of transparency, the lack of accountability, the lack of competition.” POGO’s Amey said. “Now that we’re moving into production OTAs, we have to seriously consider how we are using them; whether we are using them as intended, whether we are getting the goods and services that we really want and need, whether we are getting them at the best cost and prices and [whether] we are using this procurement vehicle as a way just to circumvent the rules and have contractors not have the administration and oversight they need to hold them accountable. I’m just afraid this is going to result in a lot of waste, fraud and abuse in the future.”

This is part two of a two-part special report on OTAs: Danger at High Speed. You can read about how traditional contractors are taking advantage of OTAs in part one.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Scott Maucione is a defense reporter for Federal News Network and reports on human capital, workforce and the Defense Department at-large.

Follow @smaucioneWFED