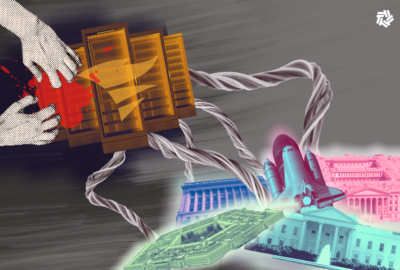

Government’s responses to major cyber breaches were well-coordinated, GAO says

The name SolarWinds has become synonymous with a scary cybersecurity crisis. It's one of at least two widescale breaches to which the government had to respond. The...

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

The name SolarWinds has become synonymous with a scary cybersecurity crisis. It’s one of at least two widescale breaches to which the government had to respond. The other is when hackers showed they could get into and take over Microsoft Exchange Server. The Government Accountability Office took a look at the federal response to these two incidents. The director of GAO’s Information Technology and Cybersecurity team Jennifer Franks joined the Federal Drive with Tom Temin with what they found.

Interview transcript:

Tom Temin: Describe briefly if you would what happened, especially with the SolarWinds, because everyone says it’s a supply chain attack. But that doesn’t really tell you what happened exactly.

Jennifer Franks: So with the SolarWinds attack at a private company in Texas, who provides network management and monitoring software to be used for either private sector needs or federal government needs, they were attacked as early as Jan. 2019. A threat actor, which we have confirmed to be the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service, breached the SolarWinds company. And in that, they were able to then insert their Trojans for the backdoor into the software that needed to be sent out to the various private sector and federal agencies for their software usage. It laid dormant for a little bit and waited for those agencies to then install that patch into their network services, and still laying a little bit under the radar. They were then able to navigate or pivot across different network connections of those attacked network entities and then potentially gain some harmful information that could intrude on the privacy of our citizens.

Tom Temin: All right, and of course, it affected industry also, and even massive attacks on industry become the government’s affair. So what you looked at then here, as GAO was just the, what, the quality of the government response to it?

Jennifer Franks: Yes, this review was definitely regarding the quality. We didn’t do a deep dive analysis into the forensics of what happened, starting at the indicator compromised to the remediation of those agencies that were potentially impacted. What we did do is look at how a cyber unified coordination group, which was made up of individuals from the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), the FBI, the Office of the Director of Intelligence, and then NSA, we looked at how that UCG really came together to respond to those high profile incidents. And there were two different UCGs stood up, one to respond to the SolarWinds and another to respond to the Microsoft Exchange vulnerabilities. And they were able to collectively come together to share information, and then collaboratively work to issue additional communications to aid in the agency’s response and recovery efforts.

Tom Temin: So that is to say they didn’t stumble over each other and send conflicting signals, but they acted like some sort of a string quartet, you might say?

Jennifer Franks: Absolutely. And it’s very helpful to agencies to have that information sharing component with that one sound, one voice so that they don’t get confused as to which agency has the higher precedence for responding to in terms of this.

Tom Temin: So does it appear that they had maybe thought about this ahead of time, what would happen if a major type of industrial grade breach happened, how they would react? And I guess my secondary question is one, do they know what they were going to do in advance? And secondarily, it looks like CISA became the point of contact for everyone, even though other agencies were helping out in the background?

Jennifer Franks: Yes, absolutely. So the the mission and vision of CISA is to coordinate those cybersecurity response efforts for the government, they are to now to be that voice for everybody to look for, to provide that initial emergency directives, response efforts that charge to kind of collectively provide information sharing based on the persistent cyber threats or even in the circumstances of responding to this type of cyber event. So yes, CISA does have the lead this effort, and they definitely took the responsibilities for helping agencies to collectively review what could have been impacted for their environment.

Your question about what they prepare, did they assume this was going to happen? It’s not that they assumed a SolarWinds or Microsoft Exchange vulnerability would happen. But a UCG has been established for quite some time. And they often stand up for response efforts to high profile events such as this. So this was not their first time coming together. But every agency is thought to have their own incident response plans and their procedures and they also test those plans, which also then navigate into contingency planning efforts. Should there be a disruption in your services, what happens next? Who was responsible? And how do you get to the recovery remediation phase. So the UCGs come together to aid that information sharing process for federal government agencies that could be impacted all at once.

Tom Temin: We’re speaking with Jennifer Franks, she’s director of information technology and cybersecurity issues at the Government Accountability Office. And so while Russia was doing SolarWinds, it’s almost like Ukraine and Taiwan. China was going after Microsoft’s Exchange Server, and similar type of response quality did you find there also?

Jennifer Franks: Yeah, absolutely. Very similar. So based on the self-reported data from the 23, civilian CFO agencies, all the agencies perform forensic triage are required by CISA again, to looking at CISA as the governance authority to provide them that initial emergency directive of how they should be responding and what they should be looking for in their various environments. And zero of those 23 civilian agencies actually reported this image exchange vulnerability as a major incident to Congress. So that was actually very beneficial for all the agencies to know that it did not majorly impact either their agency networks.

Tom Temin: And what about the Defense Department response to this because often they operate on their own relative to the civilian side? And there’s a lot of culture behind that. But how do they do with respect to the SolarWinds and the Microsoft Exchange hacks?

Jennifer Franks: So that is actually a really good question. And our primary focus was on the agencies responsible for responding to the SolarWinds and Microsoft Exchange Server incidents, which is why I highlighted the 23 civilian CFO at the agencies on how they responded to this and whether they did or did not potentially declare this as a major incident. We do, however, know that DoD did not declare either event as a major incident, although we didn’t really do a deep dive at any of these agencies. For that the review, like I noted it looking at the indicator of compromise through the recovery and remediation phases. We do have ongoing work at DoD, specifically under the mandate included in the fiscal year 2021 National Defense Authorization Act. And in this mandate, we are indeed looking at DoD cyber incident management and efforts to mitigate risk of future attacks. That review will come out a little bit later this year.

Tom Temin: And any lessons learned for the other civilian side from this, or did they pretty much go by the playbook and everything was hunky dory?

Jennifer Franks: Yeah, that’s interesting that you mentioned the playbook because that cybersecurity executive order that was issued May of last year, definitely had a cybersecurity playbook implemented in one of the action items that they are to undertake at this time. And that playbook was issued in November of 2021. But the lessons learned for this report really look at how these 23 civilian agencies categorize their lessons learned either in the positives or in the negative practices. So looking at the positive, the agencies coordinated with private sector, which is really a strong plus. And then they were able to effectively coordinate with each other, which is also really good for responding and recovering from such a high profile incident. And these efforts really didn’t lead to desirable outcomes. Specifically, agencies highlighted coordination allowed the federal government to identify this large scale SolarWinds event and then respond quickly. And it also provided increased visibility on the status of patching and then exploitation cases of the Microsoft Exchange vulnerabilities. It also again provided ways for the government to now build some trust with the private sector. So then, in the future, should another high profile event impact us, we have a way of working together collaboratively to respond to those significant incidents.

Now for the negatives though, the federal government agencies did indeed identify some challenges or undesirable outcomes, specifically, agency classification levels became kind of difficult for agencies, given the information sharing that was desired between law enforcement, private sector and even intelligence groups. And challenges with this classification made it often difficult to communicate timely, and sometimes time consuming.

Tom Temin: All right now, over the years, GAO has made about 47 million cybersecurity recommendations. I’m exaggerating. Did you have any new ones this time or this was just kind of a look see? And folks, here’s some things to keep in mind type of report.

Jennifer Franks: That’s a good question. I’m gonna have to use that 47 million sometime soon. But no, we did not make any new recommendations in this particular report. The intent for the report was to be a primary descriptor regarding the incident. So really just going through what happened and that descriptive timeline from indicator compromise to recovery. From a description perspective, but we do have many, many existing recommendations out there that need to be fully implemented, which we continually highlight. And I noted the DoD work, but we have several other reviews ongoing looking at cyber incident response and federal agencies and we will definitely continue to identify areas of improvement.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Tom Temin is host of the Federal Drive and has been providing insight on federal technology and management issues for more than 30 years.

Follow @tteminWFED

Related Stories

SolarWinds’ transparency trying to ensure others are safer from cyber attacks