Exclusive

SPECIAL REPORT: Failure is an option for DoD’s experimental agency, but how much?

The Defense Innovation Unit finally shows its cards on what it's been working on the past few years.

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

Since 2015, millions of dollars have been invested in the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit, the agency watched as some of its projects fell flat, and only about 23% the organization’s completed projects ended up in the hands of troops — but the thing is: DIU is completely fine with that.

DIU’s success statistics, delivered in a July report card to Congress, are the first long-term numbers to come out of the Defense Innovation Unit (formerly the Defense Innovation Unit-Experimental) since its inception.

The metrics, which also address time-to-contract and other areas, highlight a vexing dichotomy currently playing out in the Defense landscape: How can the world’s largest military field state-of-the-art technologies faster to counter China and Russia without compromising oversight and opening the door for waste?

While successful DIU experiments ended up, or will end up, as technologies that will protect service members from drones and detect cyber vulnerabilities on DoD networks, 77% of completed prototypes DIU invested in failed to make it to contract or have yet to make it to contract. That leaves millions of taxpayer dollars on the table, which can sometimes be a hard sell for lawmakers. Congress remains at least marginally skeptical of the program built to convert private cutting edge technology for military use.

“We take our oversight role seriously, and continue to monitor the number of successful DIU project transitions,” the House Armed Services Committee Communications Director Monica Matoush told Federal News Network.

The Pentagon admitted DIU isn’t yet at its platonic ideal.

“DIU is still improving,” Lisa Porter, deputy DoD undersecretary for research and engineering said Sept. 23 at a Center for Strategic and International Studies event in Washington. “At some level if you ask myself or DIU Director Mike Brown, we are never going to be satisfied because we’re going to be pushing the metrics from the report. I think given how young it is as an organization, it’s made great strides in the metrics that matter.”

Congress and the Pentagon see potential and importance in the small agency.

“If we were transitioning 100% of our projects, then we wouldn’t be leaning far forward enough. We wouldn’t be taking enough risk,” Mike Madsen, DIU director of strategic engagement, told Federal News Network. “That equilibrium spot would not be getting innovation for DoD. One of the things we are looking at as we go forward is how we can take some of the transformative projects and make sure we have robust transition mechanisms in place.”

DIU’s report is the first look into how the initiative is operating, how it judges its successes and what it envisions for its future.

Three years of DIU

The update from DIU spans from June 2016 to March 2019. What’s important about those dates is it completely omits the “lost year” of DIU, from its creation in 2015 to the announcement of DIUx 2.0 in May 2016.

During that year, DIU was reluctant to invest, and Silicon Valley companies were wary of DoD. Then-Defense Secretary Ash Carter noted the tension, proclaimed DIU was starting over and placed Raj Shah, a tech entrepreneur, at the helm of the reboot.

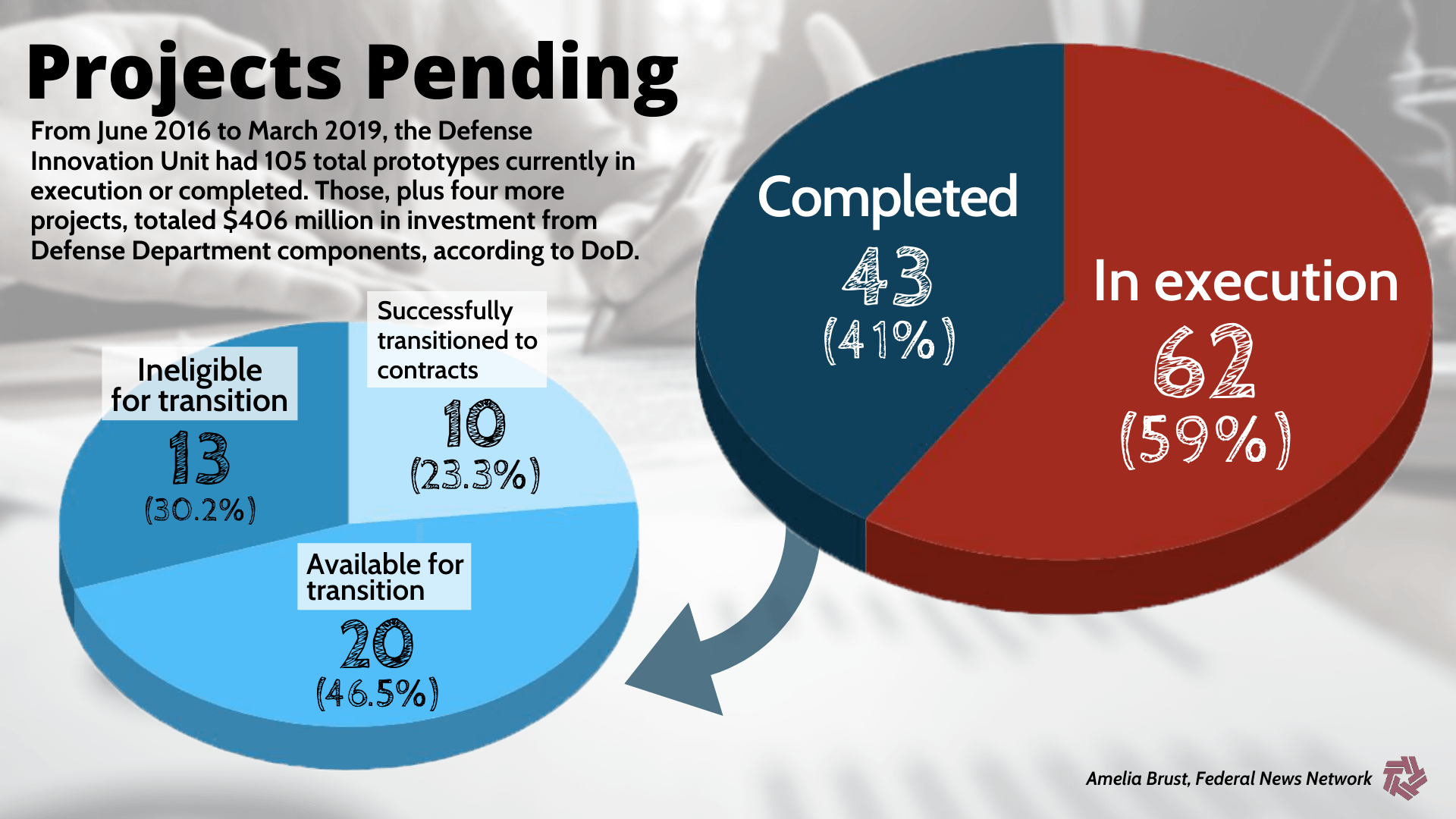

Since then, the agency undertook 109 projects, which included 105 prototypes, three experimental procurements and one prize challenge, according to documents reviewed by Federal News Network.

Of those projects, DIU completed 43 over the two-and-a-half years the report covered, and 10 of those successfully transitioned into DoD contracts or to other transaction agreements — speedier procurement arrangements between DIU and companies for the fielding of projects. Another 20 projects are currently eligible for transition, but have yet to find a home. The other 13 failed.

All that comes out to about 23% as the success rate so far for DIU completed projects.

So how does that stack up? Clearly, there is no other agency like this in government which DoD can compare itself to, but the business world may provide a glimpse of association.

Gina Colarelli O’Connor, professor of innovation management at Babson College Wellesley, Massachusetts, said industry uses a rule of threes when it comes to R&D. She used the term discovery for initial research, incubation for the prototyping phase and acceleration for scaling products to test markets.

“For any one product that is accelerating, you need three that are incubating and nine in discovery,” she told Federal News Network. “If DIU has a 23% success rate, it’s close with industry. The most important thing is that they are failing fast and failing cheap because the cost of doing that are much lower than if you just had an idea and you put it in the field.”

The rule of threes standard calls for about a 33% success rate.

In the venture capitalist world things are much looser. O’Connor said for every 100 ideas, 10 will be put into incubation, and then the hope is that one breaks through into acceleration as a “blockbuster” product.

“The 1% blockbuster covers all the rest of the investments. They look at it from a financial model,” O’Connor said. “In an organization like the military we aren’t looking at it like a financial model at all. We are looking at what impact the product has on what the military does.”

Wes Hallman, senior vice president of strategic programs and policy at the National Defense Industrial Association, said it’s important for DoD to try a lot of ideas.

“If the national security community wants to benefit from the innovation sector, then it has to be prepared for a similar level of failure to some of those private companies,” Hallman said. “There’s failing smart and there’s failing dumb, so the question is how much did you pay for that failure.”

The answer to that is somewhat subjective. DIU’s 2019 budget was $44 million — no small sum — but also a tiny part of the Defense budget. Most of the funding for projects comes from DoD customers, though. DoD components spent $406 million over two-and-a-half years for projects initiated by DIU.

It also depends what DoD gets out of those contracts, meaning are they blockbusters for military use or just mediocre. None of the 10 transitioned projects are the ultimate fighting weapon, but they do save lives, strengthen network security and save money.

For example, one completed and transitioned project used electronic signals that disrupt the remote control of drones to protect service members transporting dangerous and explosive chemicals.

DIU transitioned Citadel Defense Company’s Counter-Unmanned Aerial Systems technology to protect service members transporting dangerous materials.

Success rate isn’t the only thing the report focuses on, however. Madsen said DIU’s mission is to build the connective tissue between DoD and novel technologies. While some of that means experimenting with products, it also means trying new contracting methods and ways of bringing in companies that usually don’t work with DoD.

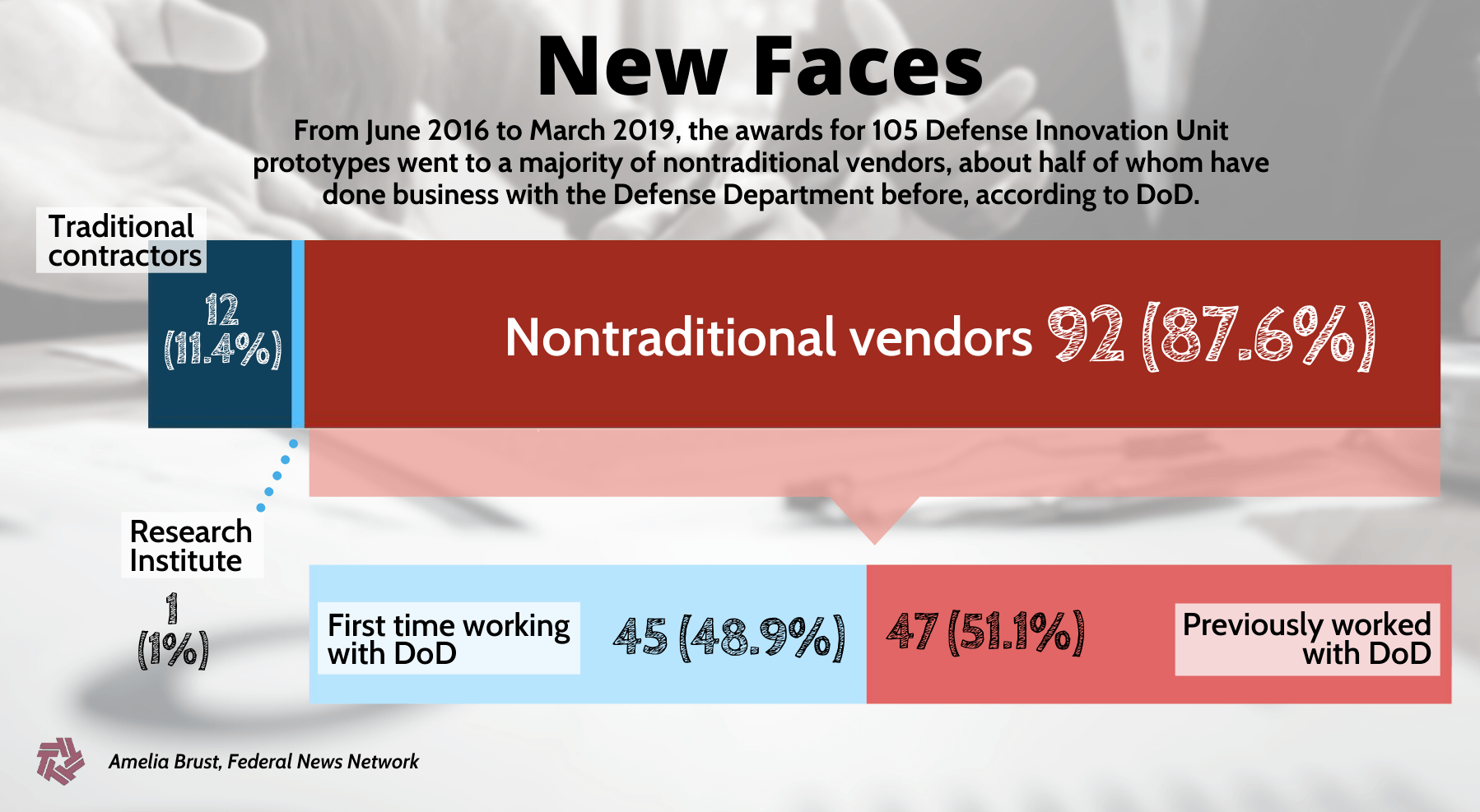

According to the report, of the 105 prototype agreements DIU awarded, 12 went to traditional vendors, one went to a research institute and 92 went to non-traditional companies. For 45 of the non-traditional companies, it was their first time working with DoD. Non-traditional companies are ones that have not done work with DoD for one year or more.

DoD explained in its assessment of the Defense industrial base that as it counters China and Russia, it’s more important to expand that base than ever.

“We are trying to grow the national security innovation base,” Madsen said. “What we do is we lower the barriers to entry to the Defense marketplace and get access to that technology in the agile companies that are developing those things. Non-traditional does not necessarily mean small business. We do work with a lot of small technology companies that are very agile. We work with large technology companies.”

Part of bringing in the companies is getting them on contract quickly for prototypes.

DIU’s report is candid about its failure to meet its goals in that aspect. The average time to contract for DIU is 187 days, three times the self-imposed benchmark of 60 days. DIU says now that it has more rapid contracting methods at its disposal, like other transaction agreements (OTAs), it expects the timeline to drop below 100 days. DIU got its OTA authority in 2018 and so far awarded three OTA contracts.

Deliver transformation across the military

The report also outlines DIU’s more philosophical goals, and how the agency will grow over time as well.

DIU plans to work on at least five projects a year that have “the potential to deliver transformative impact across the military” — think of those blockbuster venture capitalist ideas.

“These projects can scale across DoD, save lives and/or taxpayer dollars in significant numbers and substantially enhance military capabilities,” the report states.

DIU is currently working on seven projects it deems transformative.

Madsen said one of them came from a cyber challenge.

“What it does is it uses artificial intelligence coupled with cybersecurity to automatically detect and mitigate cyber vulnerabilities,” he said. “We think there are some transformative properties there. We think that will be able to scale across services.”

DIU also explained a new methodology for how it chooses projects, something Congress was concerned about in the past.

This year the agency established a Defense engagement team to continuously scan DoD for new “high-impact projects and to see out opportunities to scale existing projects.” It also created a commercial engagement team to “regularly assess venture investor portfolios, understand the state of commercial technology and identify which companies might be candidates to respond to DIU solicitations.”

Related Stories

For the latter end of the acquisition process, DIU created a project pipeline review process to regularly check on current projects’ cost, schedule, technical performance data and transition plans.

One last thing DIU did was to expand its lines of effort. It brought into its fold the National Security Innovation Capital (NSIC) and the National Security Innovation Network (NSIN).

NSIN is a collaboration between DoD and the academic community to accelerate technological research. It has more than 2,500 members.

“The new brand identity more clearly represents the vision of the organization: a national network of commercial innovation hubs and top universities to which the department can export its most complicated problems and from which it can import novel concepts and solutions,” Morgan Plummer, NSIN managing director, said in a Navy press release from May.

The NSIC makes investments in hardware usable by DoD and industry in areas where the Pentagon feels its supply chain is vulnerable to shortfalls and tampering, according to DIU’s website.

DIU asked for $25 million for NSIN in its 2020 budget request and $75 million for NSIC.

Congress, however, has other plans, based on some of its skepticism of DIU as a whole.

Congressional reaction

Since DIU’s conception, its relationship with Congress has been complicated.

Congress understands the need and the benefit of DIU and it spelled out its feelings in the conference report that accompanied the 2017 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).

“We remain cautiously optimistic that the changes to organizational structure and functions of DIUx could become important tools for the Department of Defense to engage with new and non-traditional commercial sources of innovation, as well as rapidly identify and integrate new technologies into defense systems,” the report states. “The conferees believe that outreach to commercial companies, small businesses and other non-traditional defense contractors, in Silicon Valley and across the nation, will be a key element in all efforts at modernizing defense systems and pursuing offsetting technology strategies.”

That cautious optimism remains today. The House’s version of the 2020 Defense authorization bill originally nixed the $75 million DIU requested for NSIC.

“In our constrained budget environment, the committee considered the $75 million of funding for National Security Innovation Capital was possibly duplicative to other department efforts, and reduced the funding,” House Armed Services Committee spokeswoman Monica Matoush told Federal News Network. “The funding was subsequently restored via an amendment on the House floor.”

Still, lawmakers sent a message.

That’s not the only concern the committee expressed either.

“We believe the department should work to ensure the organization is properly nested within the overall DoD science and technology ecosystem in order to continue to strengthen the Department’s ties between private industry and all of the Department’s innovative players, which includes the DoD laboratories, the DARPA and institutions of higher education,” the committee stated after receiving the report from DIU.

The Senate Armed Services Committee and the Appropriations Defense Subcommittee did not provide a comment on the report.

Madsen said DIU is happy to engage in discussion about its operations with Congress.

“We believe that by leveraging commercial technology we are advancing Congress’ investment,” he said. “We are stretching that dollar a little bit further by applying some minor customizations to commercial technologies for the Defense Department to solve some of those challenges. Our sense is we think the relationship with Congress has improved, but we are not going to sit back on our haunches and be happy and satisfied with that. We are going to continue to tell our story on the Hill and articulate the return on investment.”

Matoush said the House Armed Services Committee still appreciates the role of DIU.

“The committee believes the department’s DIU fills a critical role in the larger defense innovation effort, not only through the projects that it takes on, but the connections it forms between small and innovative companies and the national security community,” she said.

This isn’t the first time DIU received criticism from Congress though.

When the conferees of the 2017 NDAA said they were cautiously optimistic about DIU, they also, in the same breath, fenced funds from the agency.

The conditions for freeing those funds surrounded many of the same concerns DIU addresses in its 2019 report.

More Defense News

In December 2016, Katherine Blakeley, then a research fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments and now the director of strategy and analysis at Boeing, explained the lawmakers’ thinking.

“Congress expresses a significant hesitation and reservation about the impact of DIU and whether it’s structured to actually affect what it says it’s going to affect,” she told Federal News Network. “There has been a considerable strain of skepticism among members of Congress that DIU is organized and structured and has the right plan, that it promises it can bring new entrants to the defense market to the table, and then most importantly that it can actually deliver on bringing new technology where it matters, which is to the warfighter.”

Despite the tenuous relationship between Congress and DIU, it seems like the agency is here to stay.

In August 2018, then acting-Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan signed a memo redesignating DIUx (the “X” standing for experimental) as just DIU.

“Removing ‘experimental’ reflects DIU’s permanence within the DoD. Though DIU will continue to experiment with new ways of delivering capability to the warfighter, the organization itself is no longer an experiment. DIU remains vital to fostering innovation across the Department and transforming the way DoD builds a more lethal force,” Shanahan wrote.

Copyright © 2024 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Scott Maucione is a defense reporter for Federal News Network and reports on human capital, workforce and the Defense Department at-large.

Follow @smaucioneWFED