Virginia's senior senator demanded a briefing after a news report prompted more allegations of substandard housing conditions on military bases.

Virginia’s senior senator is pressing the Defense Department for answers after yet another exhaustive media report documenting health, safety and other deficiencies in military base housing.

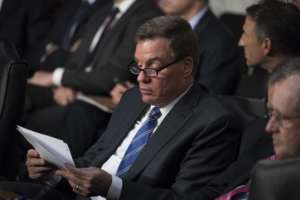

In a letter to Secretary of Defense James Mattis, Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.) demanded a briefing from Pentagon officials on what they’re doing to handle alleged failures on the part of the companies that operate the military services’ privatized on-base housing.

The issues were raised in the latest of several lengthy investigative reports on military housing by the Reuters news agency. It found multiple cases in which the firms allegedly refused to deal with serious mold, water intrusion and vermin problems, sometimes forcing them to move off-base at their own expense, and in at least one case, leaving the family to conclude its best course of action was a earlier-than-planned departure from military service.

“This is not the first time that unhealthy conditions in military housing have been documented. In November 2011, I was made aware of similar complaints regarding mold in private military housing in the Hampton Roads area in Virginia,” Warner wrote. “Working with Navy officials and impacted military families, I strove to ensure that both the Navy and Lincoln Military Housing implemented a plan to reduce these hazards. As a result, LMH agreed to offer free mold inspection to any resident requesting the service, to hire an independent professional engineering firm to survey the conditions, to update training for maintenance teams and more; the Navy also committed to improving tracking tools and enhancing oversight of property management performance. But today it appears that these changes were insufficient or ignored.”

The military services’ decision to privatize their housing was made in the 1990s at a time when officials were searching for ways to improve living conditions in what were then government owned-and-operated homes. Housing was falling into disrepair at an alarming rate back then, and as a general matter, the privatization program has been viewed by policymakers as an overwhelming success.

However, concerns about companies’ failure to deal with substandard conditions are not isolated to Virginia, nor Naval installations. This fall, the Army devised a plan to begin testing houses that were built before 1978 for lead exposure. Those actions were taken in response to another Reuters investigation, which documented more than 1,000 small children whose blood tests, administered by on-base clinics, had shown elevated levels of lead.

The Army is starting with a sample of 10 percent of those homes, and plans to finish the inspections by the end of the year, said Jordan Gillis, the assistant secretary of the Army for installations, energy and environment.

“The Army Corps of Engineers is going to produce a report for us that will really give us a baseline understanding of where we are, so then we’ll be able to decide what the appropriate next steps are,” he said. “Whether that’s additional inspections or additional mitigation, we don’t know for sure, but that should give us a good baseline to move out from.”

The inquiry involves not just lead paint — which the Army does not consider dangerous if it’s been properly covered and contained by subsequent layers of non-leaded paint — but other sources of lead as well.

“We believe encapsulation is an effective approach, but we’re conducting inspections to ensure that it is in fact effective,” Gillis said. “While we’re in there, we will also test water at the tap for the presence of lead. You can be contaminated or exposed through sources other than lead paint, and water is one of them. So we’ll test water at the tap, and we’ll do a visual inspection for the condition of any asbestos as well.”

The Army says it’s accommodating families who have asked to move out of their current houses over lead or asbestos concerns, but says only a handful have asked to do so. However, a fact sheet produced by the Army itself notes that most children who’ve been exposed to lead don’t exhibit any immediate symptoms, and blood tests are the only way to know for sure that they’ve been exposed in ways that might be harmful.

The Reuters investigations are not the only indication of substandard living conditions in privately-managed on-base housing.

The Defense Department’s inspector general has several recommendations that the Pentagon has not dealt with to the IG’s satisfaction, including from a 2015 inspection of military housing in the national capital region.

That review, which examined a sample of housing at two bases — Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling in Washington, D.C., and Fort Belvoir in Northern Virginia, found 316 separate electrical, fire, and other safety and health problems.

Among many other recommendations in its 2015 report, the IG said the Army and Navy should conduct more routine inspections to ensure their housing contractors were complying with standards.

“Guidance received from the [office of the assistant secretary for installations] prohibits Army personnel from conducting health and welfare inspections of privatized homes,” officials wrote at the time. “Lack of available resources and projected future reductions in resources do not adequately provide for or allow additional oversight of housing facilities.”

That, in a nutshell, is a key part of the upshot of the latest Reuters investigation.

Families living in military housing can’t complain to state and local officials who would otherwise handle health concerns or myriad other tenant protections offered under state laws. That’s because the houses are on military property. But the military services themselves have tended to take the position that it is not their business to involve themselves in individual landlord-tenant disputes.

The Naval Facilities Engineering Command, which oversees all of the Navy and Marine Corps’ privatized housing contracts, has only “a limited role” in day-to-day operations, NAVFAC’s assistant commander, Scott Forrest told the news agency.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jared Serbu is deputy editor of Federal News Network and reports on the Defense Department’s contracting, legislative, workforce and IT issues.

Follow @jserbuWFED