Officials considering updates to how security clearance process treats mental health

Officials considering updates to how security clearance process treats mental health

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

Defense and intelligence officials are considering updates to psychological and emotional health questions on security clearance forms as part of a long-running effort to assure employees that seeking out mental healthcare won’t affect their clearance status.

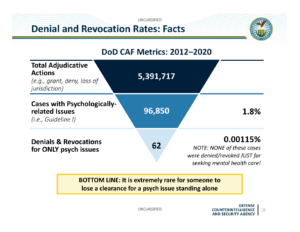

Between 2012 and 2020, the Defense Department’s Consolidated Adjudications Facility made more than 5.4 million adjudication decisions. Of those, 96,850 cases — about 1.8% — featured issues related to psychological guidelines. And within those cases, only 62 clearances were denied or revoked solely due to the person’s psychological issues, according to data published by DCSA.

Officials say those numbers help illustrate why it’s extremely rare for a security clearance to be denied or revoked solely due to mental health issues. But they acknowledge a stigma still persists that may convince cleared employees that it’s against their interests to seek out mental healthcare.

Mark Frownfelter, assistant director for the Special Security Directorate (SSD) within the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, says he thinks those misconceptions are partially driven by the very nature of the security clearance application, investigation and adjudication process.

“I think there’s a lot of ambiguity about how that final decision is rendered, and really, it comes down to a risk management decision,” Frownfelter said during a June 30 webinar hosted by the Intelligence and National Security Alliance. “I think, unfortunately, a lot of people make false assumptions, and believe that seeking treatment or counseling for mental health related circumstances could negatively impact that trust determination.”

Roughly one-third of Americans are anxious about their mental health, the American Psychiatric Association reported at the end of 2021. And Frownfelter pointed to a 2019 poll from the same association showing just half of Americans are comfortable discussing mental health in the workplace, while one-third are worried about job consequences if they seek mental healthcare.

“Intelligence community employees, they deal with the same stressors that everyone is dealing with right now,” Frownfelter said. “We have financial strains. We have work problems, family issues. And that will result in depression, anxiety, some turn to substances to help alleviate some of those illnesses or conditions. So it’s important that we dispel this myth about seeking support and seeking treatment, and how it could possibly negatively impact your clearance.”

Part of the stigma also stems from old wording on the Standard Form-86, the questionnaire individuals must fill out when seeking national security positions. Question 21 on the SF-86 pertains to “psychological and emotional health,” and prior to 2017, it asked whether the applicant had sought mental health care within the last seven years.

The form has since been updated to provide a significantly longer preamble to question 21 that emphasize the importance of seeking mental healthcare. And the questions have been updated to focus on five “security-relevant risk factors,” according to a presentation published by the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency:

- Court actions related to mental status or court ordered treatment

- Potential harm to self/others (i.e., inpatient hospitalization criteria)

- Certain conditions which may, by their very nature, impact judgment and reliability

- Non‐adherence to care (if aforementioned conditions exist)

- Self‐identified concerns regarding mental health

Marianna Martineau, assistant director for adjudications at DCSA, says the agency has sought to destigmatize mental healthcare in DoD and the national security community by focusing on mental fitness similar to how the military views physical fitness.

Within the security clearance adjudication process, that means it’s considered a positive factor when an employee seeks out mental healthcare, Martineau says. It’s also considered by adjudicators under the “whole person concept,” where security clearance determinations are supposed to be made based on the totality of an individual’s actions, including mitigating factors, rather than just individual disqualifying factors.

“We view getting mental health care positively because you as an individual are acknowledging that you need help, and you’re going out and getting it,” she said. “As a result of getting the assistance that you need, whether that’s counseling or medication or a combination, therapy, whether it’s spiritual assistance, whatever that assistance may be, you are often avoiding the undiagnosed consequences that come out in other ways, like alcohol and drug involvement and financial concerns.”

Trusted Workforce 2.0

Frownfelter says officials recently established a working group to look at further updating how the security vetting process considers mental health, including on the SF-86. The effort is a part of the “Trusted Workforce 2.0” initiative to reform and streamline the vetting process.

“We want to modernize those questions,” Frownfelter said. “And we want to shift from a focus on asking about treatment diagnoses to more of a behavioral approach.”

A vital component of Trusted Workforce 2.0 is “continuous vetting,” a system of automated alerts to flag when a clearance holder faces a potential issue, like a criminal incident or suspicious financial activity. The monitoring is replacing periodic re-investigations, where investigators would conduct a formal background investigation of security clearance holders every five or 10 years.

“One of the key aspects to mental conditions is early intervention,” Frownfelter said. “And the fact that we’re getting information in real time I think postures us to with this investigative process, have a well-being aspect to it, whereas before investigating everyone every five years didn’t necessarily give us that real time information where we can dedicate resources to correcting the issue much sooner.”

Michael Priester, chief psychologist in the adjudications division at DCSA, says professional psychologists and psychiatrists currently play a minimal, advisory role in security clearance cases.

“What mental health practitioners like psychologists and psychiatrists do is they render opinions on whether or not the individual’s behaviors of concern are likely to impact their judgment, their reliability, their stability, and their overall trustworthiness,” Priester said. “And so adjudicators can use this as part of a whole-person determination of trustworthiness and they will, by the way — oftentimes not rarely — disagree.”

He said the new working group is helping to provide a “great source of shared knowledge in terms of the kinds of things that matter to adjudicators” as officials consider mental health within the broader Trusted Workforce 2.0 reforms.

“A diagnosis is only going to show you so far, and I certainly agree that focusing on mental healthcare is probably the exact opposite approach we want to take,” Priester said. “We don’t want to discourage people from reporting mental healthcare, from seeking mental health care. And on the contrary . . . it’s the most common way that adjudicators mitigate these concerns.”

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Follow @jdoubledayWFED