NASA gets the gold trophy again for Best Places to Work, but it hasn’t always been that way

After NASA shut down its 30-year shuttle program, the agency started to make “small, but not easy,” changes to boost workforce satisfaction.

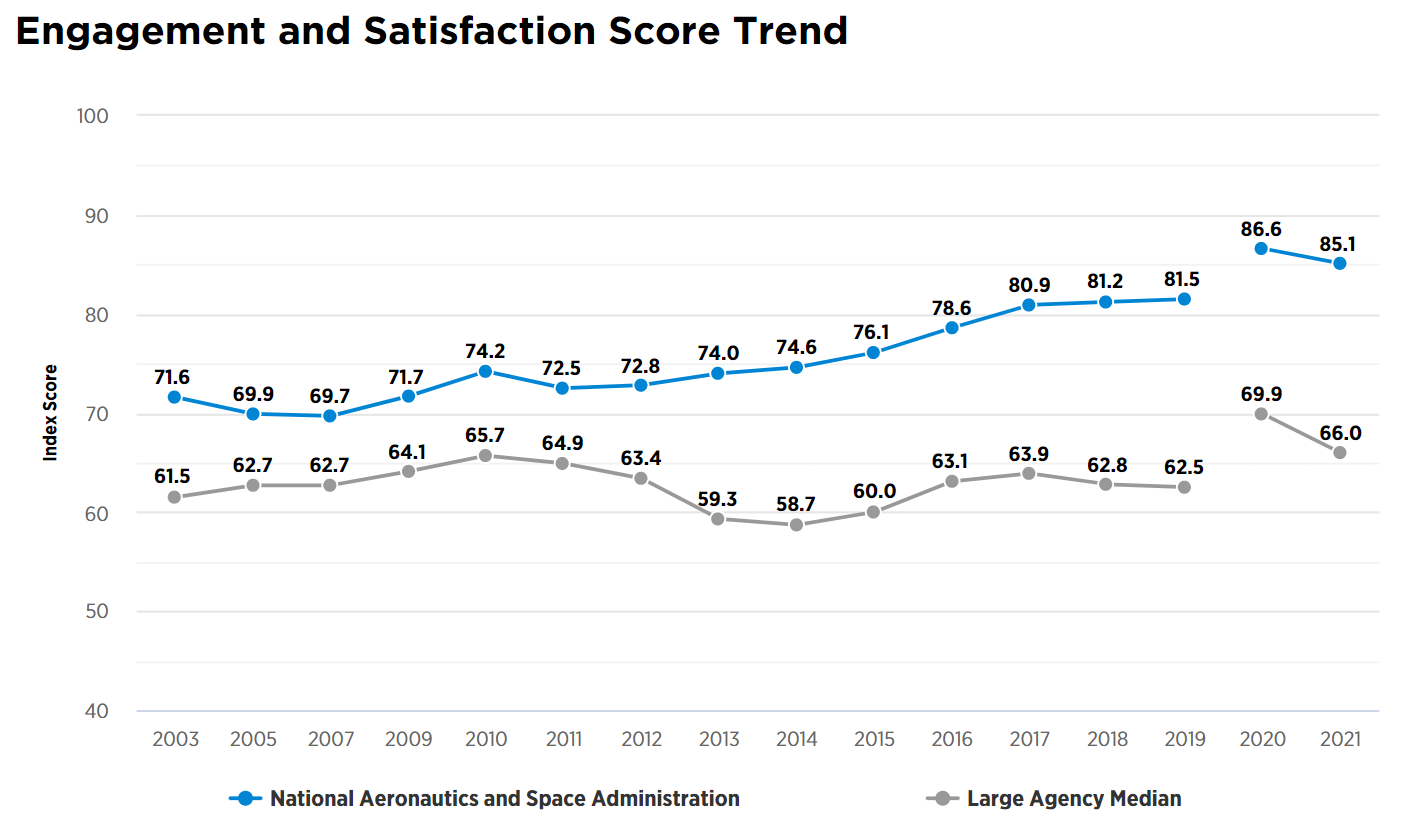

You might be applauding or lamenting the fact that NASA, now for the tenth year in a row, topped the charts for large agencies in the Best Places to Work in the Federal Government rankings. The agency has consistently scored highly for employee engagement and satisfaction, so much so that some may roll their eyes, practically expecting NASA to get the gold trophy every year. How can you compete with a workplace that sends people to outer space and puts astronauts on the moon?

But the agency, now quite well-known in the Partnership for Public Service and Boston Consulting Group’s annual standings, wasn’t always in first place. When former NASA Chief Human Capital Officer Jeri Buchholz started her job there about 10 years ago, the agency had just wrapped up its 30-year space shuttle program, with no announcements for a new space program.

“Here you have this entire workforce that had worked literally since they were interns on this program,” she explained at a recent panel with the Partnership. “You’ve taken their beautiful, soaring eagle out back behind the barn, shot it in the head, stuffed it and, literally, put it into a museum. That was the level of despair of this workforce.”

Long story short, Buchholz had her hands full, to try to turn around a workforce whose mission is to “explore the unknown in air and space.” Starting in 2011, there was nothing to attach to that mission.

To try to keep employees engaged, Buchholz, along with former NASA Administrator Charles Bolden, made a plan. It began with using data from the Best Places to Work rankings, along with the results of the Office of Personnel Management’s Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey.

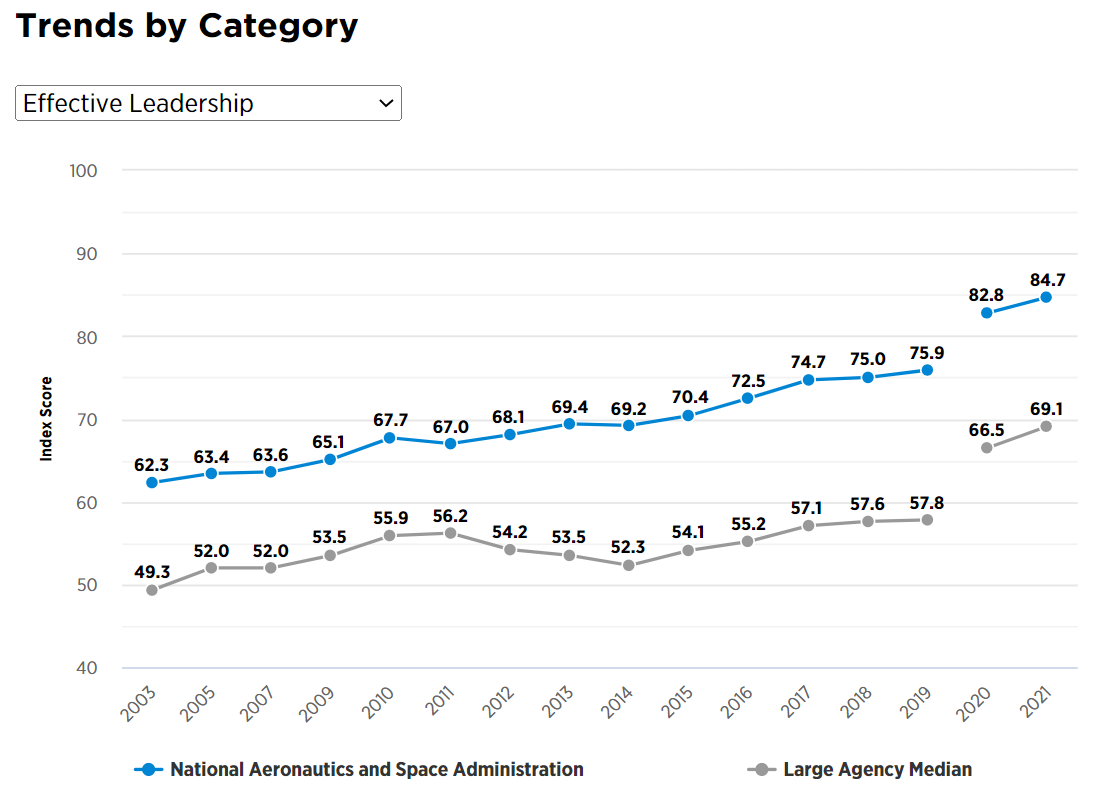

Buchholz focused on a small subset of FEVS that looked specifically at problem areas NASA was trying to address. Her data points encompassed about a dozen questions across three or four different sections of the survey. She and her team made their own metrics and plotted historical data for categories like innovation and effective leadership, as well as training and development. Once finding the focus and a few problem areas, she started working on small, step-by-step initiatives. Then, the numbers for many of those categories within NASA, like effective leadership, started to increase over time.

“It was never about being the best place to work. Someone’s always going to be at the top, someone’s always going to be at the bottom, regardless of what your score is, or how much you’ve improved over time,” Buchholz said.

Other CHCOs after Buchholz, like Lauren Leo, who stepped up to the plate in 2015, incorporated initiatives like “lean forward, fail smart,” a crowdsourcing program that asked NASA employees to share times they failed, and what they learned from it. Although not all employees participate in all the initiatives, Leo said taking incremental steps is vitally important to the bigger picture.

“We tried to incorporate small things that gave access to the broadest number of people, capitalizing on different interest areas,” Leo said.

Solutions to workforce engagement can be simple and small-scale, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the changes are easy. Another NASA initiative, called “ask me anything,” let thousands of NASA employees speak directly with the administrator and other agency leaders.

“We would ask senior leaders, ‘would you mind if you spent an hour with the workforce and someone interviewed you? We don’t know what questions you’re going to get,’” Leo explained. “‘Can you be vulnerable in that way?’”

For NASA, supervisors are often key to engaging employees and staying at the top of the Best Places to Work rankings. First-line supervisors, those slightly lower down in the management chain, are especially important to how a workforce views its leadership. By setting strong examples and doing well to “pass the baton,” you can encourage future iterations of leadership, too.

“Work is generational,” Buchholz said. “You can have one generation start a project, the next generation continued to work on it, and then a third generation of employees are the people who are actually landing the rover on Mars.”

Like every federal human capital leader, current NASA CHCO Jane Datta has faced a whole new set of problems during and since the COVID-19 pandemic. With the now much more common concept of a distributed workforce, where employees on the same team work across different physical locations, Datta said trying to draw connections among employees is all the more important.

“We know that we’re going to have to maintain the workforce in its more complex, hybrid form. We see the challenge, we know we have to address the challenge and figure out how to adapt to this new environment,” Datta said. “We’re going to pull on all those things that we’ve always pulled on, that are in our DNA, such as people-centered leadership and communications.”

Remote work wasn’t a new concept for NASA at the start of the pandemic, either. Before the pandemic, the agency had set up a “Make Anywhere a Remote Site” or “MARS” month, which experimented with the ability for agency employees to work remotely with their colleagues. Incorporating other small changes, like adding virtual launch parties to let all employees see NASA’s programs come to fruition, can also make workers feel more connected and engaged with one another, Datta said.

Even with a decade as number one in the Best Places to Work rankings, NASA remains focused on building internal successes for its workforce. Similar to many agencies, NASA’s overall employee engagement and satisfaction score dropped this past year, from 86.6% in 2020 to 85.1% in 2021, but the trend seems to still be on the upswing.

“Someday, someone is going to overtake NASA, and good for them, we will all be cheering them on,” Buchholz said.

Nearly Useless Factoid

By Abigail Russ

The record for the most overdue library book was set by Colonel Robert Walpole who borrowed a book on the Archbishop of Bremen in 1667–68. In 1956, 288 years later, Professor Sir John Plumb found the book in the library of the then Marquess of Cholmondeley at Houghton Hall, Norfolk. He returned it and did not have to pay a fine.

Source: Guinness World Records

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Drew Friedman is a workforce, pay and benefits reporter for Federal News Network.

Follow @dfriedmanWFED