Late Air Force general’s legacy leaves a mark on US national security

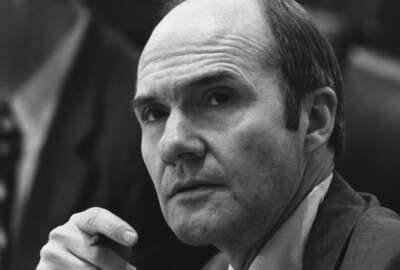

Brent Scowcroft, one of the most significant figures in US national security policy in the past half century, died this month at the age of 95.

Best listening experience is on Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Subscribe to Federal Drive’s daily audio interviews on Apple Podcasts or PodcastOne.

Brent Scowcroft, one of the most significant figures in US national security policy in the past half century, died this month at the age of 95. The retired Air Force general played vital roles in the national security landscape over the course of decades of public service, but probably none so much as how he defined the role of the National Security Council and successful management of the interagency process. Jeffrey Lightfoot is a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and a co-author of one of the many remembrances that have emerged about general Scowcroft in recent weeks. He talked about his legacy with Federal News Network’s Jared Serbu on Federal Drive with Tom Temin.

Interview transcript:

Jared Serbu: And Jeff, I want to start our discussion with a story that you tell at the beginning of the piece about the deliberations in the Cabinet Room in 1990, about how to respond to Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait. I think it’s instructive and there was there was much more debate and I guess indecision than I think I realized about what to do in response, less consensus about whether to take the what we now think of as the inevitable path of expelling Saddam. And you call those initial meetings disorganized and unfocused. What did Scowcroft see in those events and the course of action that would actually be needed that the rest of the national security team didn’t, at least at first?

Jeffrey Lightfoot: Well, I think Gen. Scowcroft is an interesting person because there he was very thoughtful not only on policy, but also on process. And, he by virtue of having been national security adviser before, for a deputy national security adviser to President Nixon, and then President Ford’s national security adviser, and then spending a lot of time thinking about the national security adviser role in the interagency process during the Reagan administration, when he was involved in looking into the Iran Contra scandal and how it played out poorly. Gen. Scowcroft had thought a lot about national security process and I think in this instance, he had a good sense of that the military was perhaps reluctant to be involved. On first blush, there was still some hangover of the Vietnam syndrome, that national interests were not the – that the conversation was not focused as much on national interest, and that the discussion was not bubbling up serious national security options for consideration with the president. It didn’t take into mind the strategic nature of this, of the question of what is the kind of international order or the sets of rules and parameters that the United States would sort of like to see adhered to in the freezing of the Cold War. They saw this as a much bigger question of one Middle Eastern country invading another but really a bigger strategic question of the kind of rules of the road that would frame an emerging post-Cold-War environment. He didn’t feel that debate, reflected that strategic questions at hand. And having spent a lot of time thinking about the process realized that that would inform a set of bad recommendations for the president. And so it really was at that point that he felt that it was important to stop that debate, reframe and regroup to ensure that the president was getting the best set of options put before him. I think that’s the important thing I think about how Gen. Scowcroft saw the role, which was – of course he had opinions and the president wanted him to share those. But his job was to ensure a quality interagency process that produced quality debate with the best options possible for the president.

Jared Serbu: Yeah and that point is kind of woven throughout your piece that to be an effective national security adviser, you really need to understand not just the global security landscape and foreign policy issues, you got to really understand how our own government works and how to make it work.

Jeffrey Lightfoot: Yeah, absolutely. And I think it requires – so a couple things that I think made Gen. Scowcroft special, almost all of his successors had come into the office saying that they wanted to try to emulate the relationship that he had with President Bush and the Scowcroft National Security Council model. And it required several things that’s proved elusive to many of Gen. Scowcroft successors. First of all, that role is so critical because it matters what kind of relationship the National Security Adviser has with the president and the Gen. Scowcroft understood that President Bush was bringing in a team of strong personalities and he wanted Gen. Scowcroft to ensure the coherence of that team so that those strong personalities work together to produce the best outcomes and not against each other. Gen. Scowcroft also had a keen eye for talent. I think one of the parts of his legacy that I’m really pleased it’s getting a lot of discussion now is the kind of mentor that he was in developing people, but also identifying strong people. And so he put a lot of thought into who would form the structure of his relatively small National Security Council team. And then the third thing that Gen. Scowcroft had that was a little unique was a personality, self-effacing ego that allowed him to not make himself the part of the policy process but focused on outcomes. And so he was able to build trust with the Cabinet secretaries to allow them to feel comfortable that their position would be brought to the president and not, you know, taken over by an egotistical national security adviser. So here you had a guy who could manage up to the president, across the Cabinet secretaries and effectively down with his staff. I think that produced an outcome that his successors have found difficult to replicate.

Jared Serbu: Going back to the Cold War piece, you know that that four years of the first Bush administration were incredibly eventful as you lay out in some detail, as the Warsaw Pact and the East-West divisions and the Soviet Union all kind of unwinding incredibly quickly. And I think President Bush usually gets most of the credit for handling all of that pretty deftly. But how much of it was really Scowcroft and his thinking and his advice?

Jeffrey Lightfoot: Well, it’s funny because first of all, I think Gen. Scowcroft would be the first to tell you that the president deserves all that credit as the visionary and the elected official, and certainly you had Secretary Baker played a huge impact in his negotiations with the Soviets about German reunification and things so it really was a team effort. I think Gen. Scowcroft, interestingly enough, came in and framed the discussion and the debate early on. Interestingly, Scowcroft later in life after leaving government developed a bit of a reputation as something of a dub because of his skepticism of military intervention, particularly his criticism of the 2003 Iraq War. What’s funny is he came into the Bush administration, actually one of the leading hawks about the Soviet Union because Gorbachev and Reagan had had a number of arms control achievements. And Gorbachev was making unilateral military drawdowns within Europe that were politically very popular but Gen. Scowcroft saw those as militarily sort of significant but they weren’t changing the political nature of illiberal communist regimes in Eastern Europe. So Gen. Scowcroft decided let’s have a review of the Reagan policy but let’s have our own independent foreign policy that would not just let ourselves be swept away by Gorbachev’s initiative. Let’s get in front of this, which is the president’s guidance. So Gen. Scowcroft, I think help frame that debate to ensure that the changes that would be taking place in Europe were not cosmetic, but they were real. So I think that was the first thing secondarily, certainly management of this process, you saw the instinctive caution Gen. Scowcroft and President Bush shared to not revel in this moment and rub it into the Soviets’ eyes, so to speak, which might have escalated the situation. But I think Gen. Scowcroft admitted in posthumously published interviews recently that he was more cautious than President Bush about German reunification. And so I think, you know, credit for that largely belongs to the president as it should be, and probably to Secretary Baker, but certainly the care and management of this incredibly complex set of events that could have gone very badly, I think largely deserves credit to the whole administration, but certainly to Gen. Scowcroft for helping shepherd that process at a really difficult point in time. Secretary Gates, who was Gen. Scowcroft’s deputy at the time has pointed out that really never in history before had an empire collapse like that without leading to war. And I think that leaves a lot of credit to give to that administration.

Jared Serbu: I just want to acknowledge that we’re not doing justice to Gen. Scowcroft’s multi-decade national service career by focusing mostly on his time as national security adviser here. But just to wrap up on that point, what in your view is his role on the national security adviser, the National Security Council as an institution and how it’s operationalized, what it actually does within any given administration?

Jeffrey Lightfoot: So where were Gen. Scowcroft legacy, I think this is this is probably going to be the most enduring part of his legacy because we talked about the policy achievements that the administrations in which he served, which were impossible to dissociate in some ways from the president who was, really deserves most of the credit or the blame or other Cabinet secretaries. It was Gen. Scowcroft’s creation, I think of the modern NSC staff and structure and process that really has largely endured, of course, it’s evolved and changed in some ways. But it was really since he’s been around, you’ve had sort of a principals committee and a deputies committee to allow the interagency to quickly adjudicate, discuss and debate issues below the level of the presidents that the interagency process produces crisp, focused, holistic outcomes. And so that structure has largely stayed in place and has been one that many have seeked to emulate. And really the idea is not to be operational. And I think that’s where some National Security Council staff have maybe, particularly in the Obama administration, you heard stories of the NSC staff growing – becoming 400 people, whereas Gen. Scowcroft’s was more like 40 – and becoming more involved in the implementation of policy, whereas Gen. Scowcroft wanted it to be a place that could coordinate some debates across the interagency and then ensure that the best policy recommendations and options are given to the president. I think, now we’ve seen a realization the NSC staff might have gotten too big and a desire to to shrink that back down. But of course, every president sets the tone for the NSC that he or maybe she wants and so ultimately, that structure which has largely survived is going to be very based on the way the president wants to to evolve, and perhaps the personalities of other – the relationship with other Cabinet secretaries.

Jared Serbu: Is it your impression that he had a relatively small NSC staff because he wanted it that way by design? Or was that just the deck of cards he was dealt?

Jeffrey Lightfoot: Yeah it’s actually fascinating. The University of Virginia’s Miller Center has just released the second part of these incredibly in-depth interviews with Gen. Scowcroft that are really fascinating because they really delve it – you really get a sense for how much this man understood the process of working of government after having served in that job two times and having been President Ford’s national security adviser. When he was asked by President Bush to resume that role in 1989, he had deep thinking about what worked and what didn’t and he did want a relatively small staff with a good number of details, but that he had picked with minimal interference from the political types that would really be focused on the mission. And so he had a sense that if it got too big instinctively it would become operational, which is not what the NSC was supposed to do. And since then it’s certainly has – it’s tended to grow until the most current administration here has shrunk it back down.

Tom Temin: Jeffrey Lightfoot, a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, speaking with Federal News Network’s Jared Serbu. We’ll post a link to the Atlantic Council’s much more detailed commentary about Brent Scowcroft’s legacy at www.FederalNewsNetwork.com/FederalDrive.

Copyright © 2025 Federal News Network. All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Tom Temin is host of the Federal Drive and has been providing insight on federal technology and management issues for more than 30 years.

Follow @tteminWFED